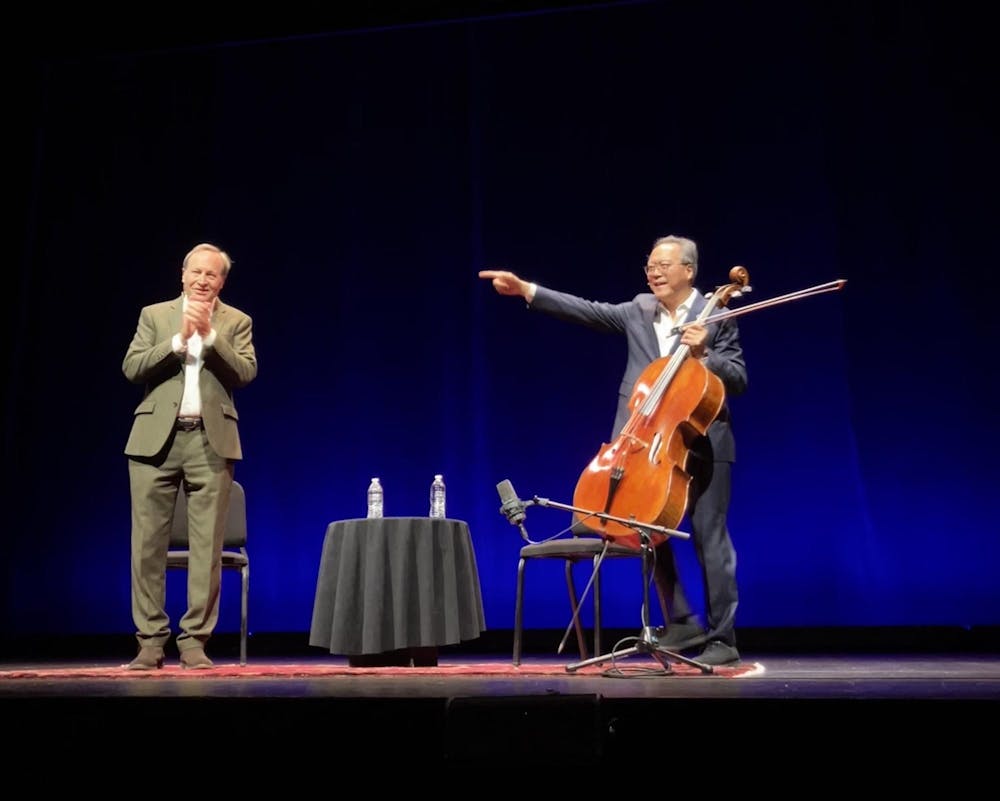

On a damp April evening, the kind that seems to hush Princeton’s campus into a reverent stillness, Yo-Yo Ma strode onto the stage with a cello in his hand at McCarter Theatre, all warmth and easy gravity. The cellist, who has for decades played in the world’s great halls and its most humble corners, was not here merely to perform. Instead, he invited the audience into a conversation: a journey through music, memory, and the quiet, persistent search for meaning in a world that often feels unmoored.

The event, “An Evening with Yo-Yo Ma in Conversation with Jeffrey Brown,” was less recital and more a hybrid of anecdotes about his musical journey, his personal and career philosophy, his aspirations for societal impact through his performances, and breathtaking outbursts of music that seem to suspend time. Ma’s smile — wide, mischievous, unguarded — set the tone. He joked with Brown, the PBS NewsHour correspondent, about his pandemic project “Songs of Comfort,” which swelled from solitary work and an excuse to stay home during the pandemic into a communal movement, gathering voices and solace in a world newly attuned to isolation.

There was a sense throughout the talk that Ma was less interested in dazzling us with virtuosity than in inviting us to listen to him, to each other, to the world. He spoke candidly of his childhood, shaped by “tiger parents” and the expectation that music was both inheritance and obligation.

“I did music, so it was all around me,” he said, “but had a big conflict because my dad wanted me to be a really good musician but also wanted me to be totally obedient. But you can never be both.” It was only at 49, he confessed, that music finally became a choice, not a mandate.

The evening was punctuated by Ma’s sudden transitions from bantering to music. The event program mentioned that there would be musical interludes, but what he would be playing and when exactly he would play was a surprise. At one point, after a particularly playful exchange about his notorious travel schedule, Ma launched mid-speech into a lush C major melody, a “song of gratitude” he described as “for the sun rising every day, for the seasons, for the trees and the grass growing.” Listening to it live, I was captivated by the seamless patchwork of pitch, technique, and musicality that only amplified Ma’s exuberance from speech into cello-playing, so projective and pure that one could not even bear to look away or not pay attention. The effect was immediate: the audience, lulled by his affability, all fell silent, breath held, as if witnessing something sacred.

It was not the grandeur of the music alone, but the sense that Ma was offering up a piece of himself, a living testament to the idea that music is not a transaction but a communion.

After a poignant excerpt from Shostakovich’s “Cello Concerto No. 1,” the conversation turned to history, the legacy of war, and the persistence of cruelty.

“One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic,” Ma quoted, invoking Shostakovich and the Cold War, before adding, “We must make sure that no death is just a statistic. Our job as performers is to keep things alive.”

He spoke of Bach’s Cello Suites as music that is “both empathetic and objective, sacred and secular.” These were not abstractions. When Ma played, the Cello Suites became a kind of prayer — sometimes mournful, sometimes exultant, always searching.

In quieter moments, Ma shared insights on searching for the soul of America in its sounds and of the “edge effect” in nature, where two ecosystems meet and creativity flourishes. Ma seamlessly wove his musical philosophy into stories of travel, collaboration, and discovery, drawing the audience into his ongoing quest to understand the connective tissue of American identity and creativity.

“Culture opens our hearts to one another. And the currency in culture is not money but trust. Sharing is a much better way to communicate than proving,” he said. At one point, he described performing in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave and at a rebuilt Notre Dame, underscoring his conviction that music belongs everywhere, not just in the gilded confines of concert halls.

Ma’s reflections wandered from the personal to the planetary. He worried aloud about the world his grandson would inherit in 2100, asking what kind of wisdom and what kind of trust we might leave behind.

“I wish we had a world wisdom bank,” he said, “where every individual gives dignity to every other human.” It was an appeal not for answers but for the ability to listen — for the kind of listening that music, at its best, demands and rewards.

The evening’s most unexpected moment came when Ma invited the audience to sing a single note, D natural, while he played Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 1” in G Major. Learning one line at a time for a month, it was the first piece he ever learned on the cello, he explained, and it became, in that instant, a symbol of trust and resolve. Our pitch was imperfect, wavering, but undeniably communal. For a moment, the boundaries between artist and audience, between stage and world, dissolved.

In the end, Ma’s performance was less about mastery and more about presence. He reminded us, gently but insistently, that the purpose of technique is to transcend it. In a world that too often prizes certainty, Yo-Yo Ma offered instead the radical, luminous possibility of not knowing and instead just listening.

Chloe Lau is a member of the Class of 2027 and a staff writer for Features and The Prospect at the 'Prince'. She can be reached at cl2454@princeton.edu