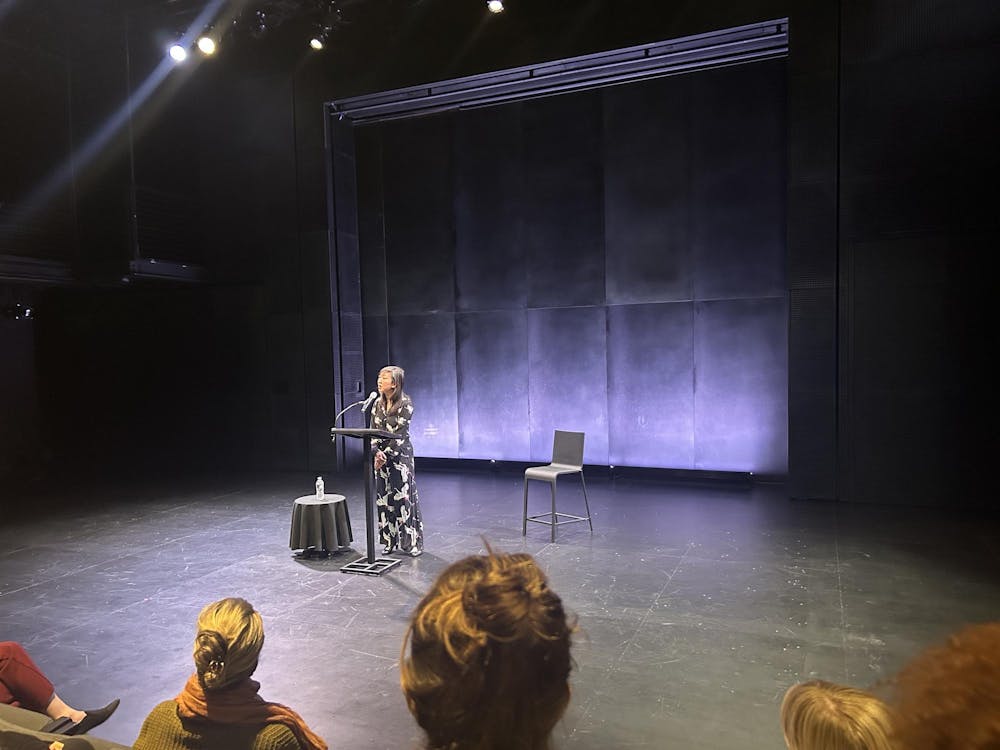

The Wallace Theatre echoed the voices of students, professors, and guests as they awaited a reading from Princeton alumna Monica Youn ’93 on Feb. 25. The lights dimmed, and Youn was introduced.

The readings were drawn entirely from her most recent work, From From, which was a New York Times Notable Book and Best Poetry Book of 2023, and was named a best book of the year by Time Magazine, NPR, Publishers Weekly, and Library Journal. The esteemed publication was available for purchase and signing at the event.

Despite her incredibly impressive background, Youn walked on stage with a graceful yet powerful humility. Her reading would provide an image of a specific racial experience told through the lens of Greek myth, while also navigating a line where the racial experience isn’t the only message to be taken from the poems.

Youn introduced the reading by expanding on the title of From From — referring to the question many racial minorities may have heard before after being asked about their location of origin and not hearing an “expected” response. She said the questions create a feeling of “in betweenness” and “a place of lack.” From a quick skim of From From, I realized that a large portion of Youn’s work was full of ancient Greek allusions — which made sense as she began the night with some mythological context. Though she does not credit it entirely for the constancy in her work, she shared that she took a Greek mythology class during her time at Princeton, which she really enjoyed.

Youn told the audience the story of Pasiphaë — a queen of Crete in Greek mythology, a witch, a relative of Medea and Circe, and as a result of a curse on her husband, mother of the Minotaur. She then told us of Crown Prince Sado — a Korean prince sentenced to death by his father, who ordered him to climb into a rice chest, where he eventually died. She connected the two characters by their subjection to dire circumstances.

She then began reading the first poem of the evening, the first work featured in From From: Study of Two Figures (Pasiphaë / Sado). The poem elaborated on how race can subject one to circumstances out of one’s control, specifically how mentioning race in a poem immediately marks the poem as a thematically racial poem. She continued to detail the figures’ containment due to their race, gender, and position, and she alluded to her containment, due to her identity, but also her role as a poet. The reading was incredibly touching; in fact, I got lost in between the telling of the context and the poem itself and simply listened intently as if it was all a story that drew me away from the second row in Wallace Theater.

Upon Youn’s reading of the first poem, I was immediately immersed in her work and powerful language — both through her written words and her impeccable presentation of them in person. She continued the theme of race throughout the rest of the night — but continually rejected the notion that the poems were solely about race.

In the second poem read, Youn spoke of “speaking truth to power” by using Marsyas, a mythical satyr who challenged Apollo to a music contest, which resulted in his death. I appreciated her continued reference to Greek mythology, which entranced me into the world her words created. She carried on with the allusions in the following poem: Study of Two Figures (Midas / Marigold). The poem used the classic tale of the King with the golden touch to symbolize certain strains within a father/daughter relationship. The parallels Youn used were particularly moving.

The next few readings dealt with a magpie representing prejudice against Asians and Asian Americans. Youn explained two contrasting views of the bird. In the Western world, the distaste for the creatures was so grand, having been unjustly blamed for the death of livestock, that they almost became extinct. However, in Eastern Asia, the birds are seen as symbols of joy. Youn used this contrast as an effective literary tool in the poems she shared with us, and I really enjoyed the imagery the bird brought to her words.

Youn’s final reading of the night returned to an earlier figure: Prince Sado. The poem, titled “Leave”, alluded to a desire to escape, which is how it is connected explicitly to Sado’s story. Still, it also portrayed a very stirring personal experience to the poet. It seems Youn cleverly chose this poem as the final piece due to its title, which is never mentioned in the poem itself, but is implied in its final lines: ”why don’t you make like a tree and …”

Despite the poem’s final words, I had no desire to leave. The reading, which totaled about 45 minutes, seemed to fly by, and I was truly captivated by Youn’s work. My post-midterm plans will include getting a closer look at her collections, and I highly recommend you all add this task to your lists as well.

Natalia Diaz is a member of the Class of 2027 and an associate editor for The Prospect at the 'Prince.' She can be reached at nd6595@princeton.edu.

Please send any corrections to corrections@dailyprincetonian.com.