In a classroom in Jones Hall, students in the Near Eastern Humanities sequence partner up to compete in the Royal Game of Ur. Originating in Mesopotamia in the early third millennium B.C.E., the oldest board game in recorded history awaits students to declare a victor in their class tournament.

This is just one way that Near Eastern Studies (NES) Associate Professor Daniel Sheffield, who has taught the course several times in the past, would encourage his class to “inhabit” the texts they studied. Students were asked to read translations of tablets to reconstruct the rules of the game and then compete during a designated “ancient board game day.”

“It’s just amazing to sit with these students and see them develop strategies,” Sheffield said, speaking to The Daily Princetonian from the backseat of an Uber in London. Sheffield is on leave, completing research at the University of Oxford for the 2024–25 academic year, but still fondly recalled his experience teaching the Near Eastern sequence.

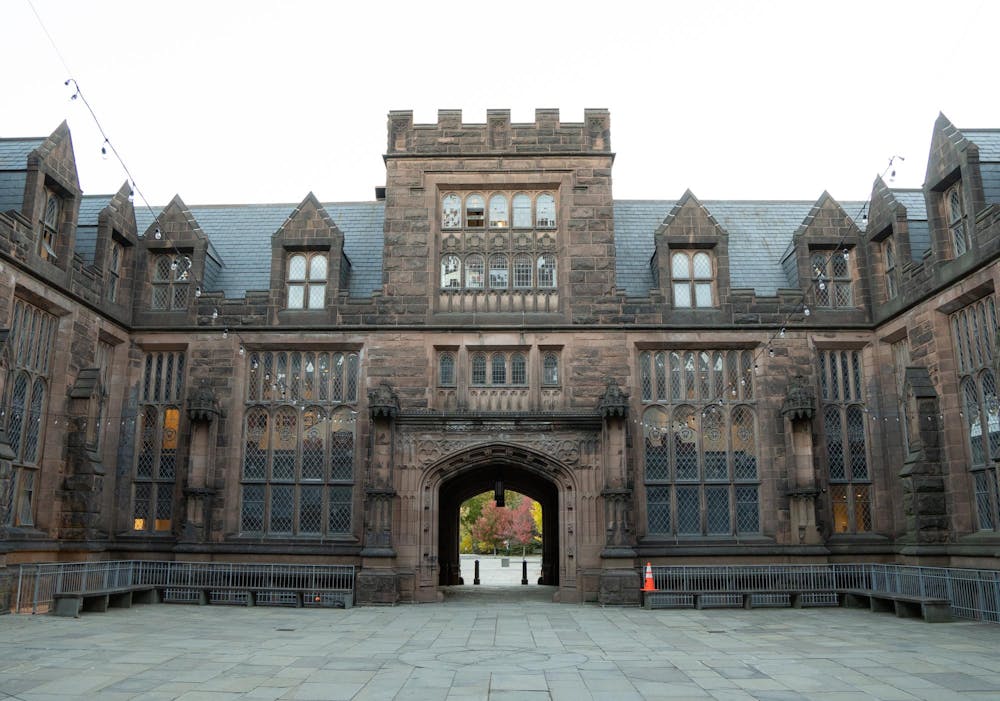

The University began offering the Western Humanities “HUM” sequence in 1992, and expanded into the East Asian and Near Eastern Humanities sequences in 2005 and 2019 respectively. These survey courses provide underclass students with comprehensive exposure to literature, philosophy, art, religion, and more.

The Western Humanities course seeks to offer interdisciplinary cultural lenses into the central question: “What makes us human?”

“We wanted to endow our students with a sense of a canon,” said Professor of Classics Yelena Baraz. “The books they read and the subjects we cover are foundational to Western thought. Though that notion can be contentious in its own right, the course does a good job of setting students up with a great basis for critical thinking.”

Though the reading lists vary slightly each year, students in the Western Humanities sequence read well-known works that span biblical antiquity through contemporary literature. By the end of the two semesters, students have engaged in close reading and analytical thinking which prepares them for the rest of Princeton’s academics and beyond.

Modeled after the Western sequence, the East Asian and Near Eastern Humanities have adapted this model to create more culturally diverse curriculums that equip students with the same critical thinking and global insight.

The East Asian Humanities sequence focuses on the humanities output from China, Korea, and Japan. While rooted in similar academic skills, this sequence seeks to open students to a world of different cultures and mediums, pushing students to engage with texts beyond the more analytical style.

“We talk about diversity, it’s not just the world of the Bible. It’s not just the Western canon, it’s so much more than that,” said Associate Professor of Korean Literature Ksenia Chizhova when talking about the benefits of the non-Western sequences. “We all want to know this shared world and this is the closest we can get to that. You expose yourself to the whole universe of other people, other ways of living the world.”

Similarly, the Near Eastern Humanities sequence focuses on Near Eastern art, literature, philosophy, religion, and science from antiquity to the present. This sequence emphasizes key texts, but also incorporates visual works and material culture, such as coins and pigments.

“I really enjoyed the methodology of the instructors and how they made sure to relate each text to broader themes and trends within Near Eastern literature,” said Davi Frank ’26, who is pursuing a major in NES.

The Near Eastern sequence recognizes that “the cultural contributions of the Near East are viewed through a western lens,” as the Humanistic Studies website puts it. For example, the world uses 60 seconds and 60 minutes to divide time due to the contributions of ancient Babylonian astronomers. For this reason, the Near Eastern sequence is particularly interested in “the original context from which [these contributions] emanated.” The course aims to convey that the Near East is not just important because of its relation and importance to the West, but also has intrinsic value.

“It’s really just an exciting environment to read texts that really aren’t that well studied with students who are seeing these texts with fresh eyes,” said Sheffield. “For me, that’s really the joy of teaching in a nutshell.”

In interviews with the ‘Prince,’ students and professors engaged in the non-Western sequences described an uphill battle to drum up interest in the courses on par with their famed Western sequence counterpart.

Apart from the fact the newer sequences have only existed for a few years compared to the Western sequence’s few decades, why do enrollments remain much lower?

An uphill battle begins

The brochures that are mailed out with Princeton admissions packets and handed out during the first-year Academic Expo highlight all three sequences equally.

“I feel like we advertise them equally, and in fact, probably more with the East Asian and the Near Eastern, just because their enrollments have been lower traditionally, than the Western HUM sequence,” said Stephanie Lewandowski, the Program Manager of Humanistic Studies.

Each year, student enrollment reflects that the Western Humanities sequence remains popular, with at least 45 out of 60 of its seats filled in the Fall 2022, Fall 2023, and Fall 2024 semesters.

In contrast, in Fall 2024, only four students enrolled in the East Asian sequence out of a 40 student capacity.

Enrollment for the Near Eastern sequence was slightly higher, with 15 students out of a possible 30, an increase from the 10 students enrolled in the fall of 2022.

For Sheffield, the growth in Near Eastern Humanities enrollment is a testament to the way students have been able to “build the hype of the class and get the word out about what we’re doing.” Still, enrollment for the Near Eastern sequence fluctuates — last semester’s 15 reflects a decrease from Fall 2023’s 22 students. This spring, the Near Eastern Sequence was cancelled.

Lower enrollment, however, isn’t always viewed as a failure of these programs.

“Some of my colleagues in the East Asian department have these really big classes where you cannot engage one-on-one,” said Chizhova, “There’s a benefit to both, but I prefer that more intimate setting. I like to get to know my students, I like it to be a dialogue.”

“You get to know the class a little better,” Frank said about his experience. “There are advantages for being a little more intimate.”

Still, the lower enrollment rate of the non-Western sequences can affect how students experience these courses, which aim to incorporate both rich interdisciplinary lectures and highly engaging discussion-based precepts.

Some students report that the small cohorts cause a collapse of this style of teaching. The East Asian sequence class Molly Lopkin ’25 took last semester, for example, had four total students, a drop from the previous year’s 14 students.

“Because it was so small, we were in this weird space where I felt like sometimes the professors were doing lecture, but also wanted to be doing discussion,” said Lopkin. “I wasn’t really quite sure what mode the class was supposed to be in.”

The answer to why these two sequences face lower enrollments might be, simply, that the texts featured in the Western Humanities sequence are more well-known.

“I think with the Western [sequence], students are kind of aware of us and these texts before they’re even at Princeton, right?” said Lewandowski.

Students who hail from the West, as most Princetonians do, might also see the Near East and East Asia as less relevant to their lives. In teaching the Near Eastern sequence, Sheffield said that he aims to challenge this perception.

“Even though it is a Near Eastern Humanities class, we talk about the relationship, for instance, of Mesopotamian literature to Greek epic and Greek philosophy,” Sheffield explained. He added that since it is “the oldest literary tradition in the world,” the impacts of Near Eastern Humanities on the rest of the world are profound.

Chizhova also referenced the influences of the non-Western cultures on the West. “I think what they [the Western sequence] really have to adopt is thinking about how the non-West feeds into this monstrous identity of the West.”

Another possible explanation for the enrollment disparity between the sequences is the impact of socio-cultural climate on perceptions of the Near East and East Asia at a given moment.

Sheffield explained how the Near Eastern sequence is often impacted by current geopolitical conflicts in the region, which may lead students to have a negative view on the discipline more broadly. “We are often at the whim of the news cycle,” Sheffield said.

“People perceive the Near East in certain ways to do with current events, and we’re always trying to sort of get students to look beyond that,” he added.

Moreover, Lewandowski explained that though some students inquire about the non-Western sequences, the Western sequences often gain traction among first-years via word of mouth. “What’s happening at those events [like the Princeton Preview and Academic Expo] is people are saying, ‘I had a friend who took the Western,’ or ‘I had a sibling that took the Western,’” Lewandowski said.

The allure of travel perks and faculty availability in Western humanities

The Western Humanities sequence offers students many opportunities outside the classroom that students of the Near Eastern and East Asian Humanities sequences do not receive. It is impossible to describe the Western sequence without mentioning what many say is its biggest perk: a fully-funded trip to Greece or Italy with your classmates and professors.

“The trip really felt like the culmination of our year’s worth of study,” said Jane Buckhurst ’27, who took the sequence as a first-year and went to Greece the following year. There, Buckhurst and her classmates passed the road where Oedipus is said to have met and killed his father, and stood by the chamber of the temple at Delphi. “It felt particularly special in that while places like Rome are sites of ancient history, Greece was the city of the myths that we had grown up reading about and then studied together.”

Buckhurst is a staff Archivist for the ‘Prince.’

As a scholar who focuses on Ancient Greek philosophy, professor Benjamin Morison recalled that one of his favorite memories from teaching the Western sequence is the first trip he took to Greece.

“I insisted that we go and see the remains of both Plato’s and Aristotle’s schools in Athens, so the Academy and the Lyceum … for me, that was thrilling,” Morison said. “I’m not sure the students were so thrilled, but I was thrilled otherwise.”

Fittingly, the tour guide often booked for the Greece trip is called Aristotle. “He’s an amazing, legendary guide,” Morison said.

“I don’t know if quality is the right word, but the Western HUM sequence is an ‘experience,’” said Lopkin. “It’s much more intensive. You have all these different teachers who are talking about things that they’re experts in. You go on trips. There’s your opportunity to go abroad. The East Asian HUM sequence doesn’t really have that.”

In addition to the trip, the Western sequence is taught by a six-person faculty team each semester, all of whom are experts in their fields. In contrast, the Near Eastern and East Asian sequences are taught by only two instructors each. This variety gives students unique opportunities to learn from faculty members with different specializations, understand the interdisciplinary nature of the humanities, and appreciate different lecture styles.

Professors also benefit from experiencing their colleagues’ lectures. “I’ve learned so many things from my colleagues. And I don’t just mean learned about the ancient world, I mean learned how to be a good teacher from them,” Morison said.

According to Sheffield, the East Asian and Near Eastern sequences also benefit from co-teaching, even with just two instructors. He described how seeing professors sit in on the lectures they do not teach lets students “[see] your professor model what it is to be a student.”

However, while the Western sequence is able to have six faculty members teaching across both semesters, the Near Eastern sequence has encountered issues running the second semester due to a lack of available faculty. Sheffield explained that though there are faculty members who focus on the modern Near East, “we’ve had a challenge in getting more faculty to commit to teaching that second half.”

Fewer available faculty members means that although many students might want to continue for the full year, that is not always possible. “Having a little bit more regularity in the way in which we offer that would be great,” Sheffield said.

However, having more instructors — whether that be faculty members or graduate students — in the classroom has benefits. For the Near Eastern and East Asian sequences, higher enrollments enable the sequences to hire graduate students, according to Sheffield, which is “terrific” because it allows graduate students to “contribute their expertise in the class.”

Last year, the Near Eastern sequence had a graduate student teaching assistant, who had previously worked in the Penn Museum and gave the students tours of museum collections when they went on trips to the Penn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “It really just adds an extra layer of enrichment for students when we have those higher enrollments,” Sheffield said.

International trips, moreover, are not offered to students in the Near Eastern or East Asian sequences. Instead, students go on a few nearby museum field trips over the course of the semester. For example, the students in the Near Eastern sequence visit the Penn Museum to see the tablets of the epic of Gilgamesh.

When asked about whether or not she would want the opportunity for an international trip, Lopkin said, “I’m not going to turn down the trip to China.”

Frank also hopes the opportunity for travel increases more generally for students in the Department of NES. “I definitely wish that there was more exciting Near Eastern, like, Middle Eastern travel in general, through the University,” said Frank.

Sheffield was also in favor of international travel, telling the ‘Prince,’ “Having a more serious discussion about international travel is one thing that I think would be terrific to possibly bring into the course.”

However, he acknowledged that there are geopolitical reasons which might complicate organizing a trip for the Near Eastern sequence. “It’s not that easy to arrange trips to many places that we do study,” Sheffield explained, referring to current regional conflicts. He added, “Iraq, Iran are basically out. We’ve talked about Turkey or North Africa as a possibility, and I hope that we can develop that in the next couple years.”

A path forward for the three sequences

The humanities sequences are and continue to be a cornerstone of the Princeton undergraduate experience, but with evident disparities between the three sequences, faculty are considering ways that they might continue to evolve in the future.

Many professors who spoke to the ‘Prince’ described how the sequences have already evolved.

Baraz recollected that the first time she taught the Western sequence, “There was not a single text that was written by a woman. And I was also the only woman teaching the course.”

Now, according to Baraz, faculty have made efforts to diversify the Western Humanities syllabus. Though the syllabus changes each year, authors that will be taught in the 2024–25 Western Humanities sequence include Marie de France, Sappho, Aimé Césaire, W.E.B. DuBois, and Frantz Fanon.

If change can intentionally and successfully happen within a sequence, it may also be possible across the three sequences. At least, that’s what professors and students from the Near Eastern and East Asian sequences hope, whether that manifests as increased enrollment, or the ability to go on international trips.

According to Chair of the Council of Humanities and Western Humanities professor Esther Schor, attitudes towards non-Western cultures are changing, too. Even though “there’s just less exposure in high school to [East Asian and Near Eastern] traditions which is limiting the sequences’ reach at the moment,” Schor said, “that will be less true 15 years from now.”

Last fall, the Program in Humanistic Studies tried something new: connecting a faculty member with a postdoctoral researcher to teach the Near Eastern sequence. For Sheffield, this is “one potential way forward in terms of just staffing the class.”

Lewandowski still has more ideas. One potential way to draw more students into the Near Eastern and East Asian sequences, according to her, is to involve students and alumni who took the sequences through a mentorship program.

She also suggested an increase in digital advertisement of the sequences via social media platforms, in addition to the current emails and physical fliers.

As Lewandowski put it, “Nothing is off the table.”

Nikki Han is an assistant News editor for the ‘Prince.’

Sedise Tiruneh is a staff Features writer and staff writer for the Prospect.

Please send any corrections to corrections@dailyprincetonian.com.