When you think of compost, the fragrance of fresh coffee may not be the first thing you imagine. However, coffee rests at the heart of a longstanding sustainability partnership at Princeton.

Since Coffee Club opened in 2019, the student-led coffee shop has donated discarded coffee grounds to the Sustainable Composting Research at Princeton (S.C.R.A.P.) lab for composting operations. “The founder of Coffee Club reached out to our office to see how we could partner,” said Gina Talt ’15, Food Systems Project Manager at the S.C.R.A.P. lab. With coffee grounds being a convenient and effective compost material, the partnership was set in motion.

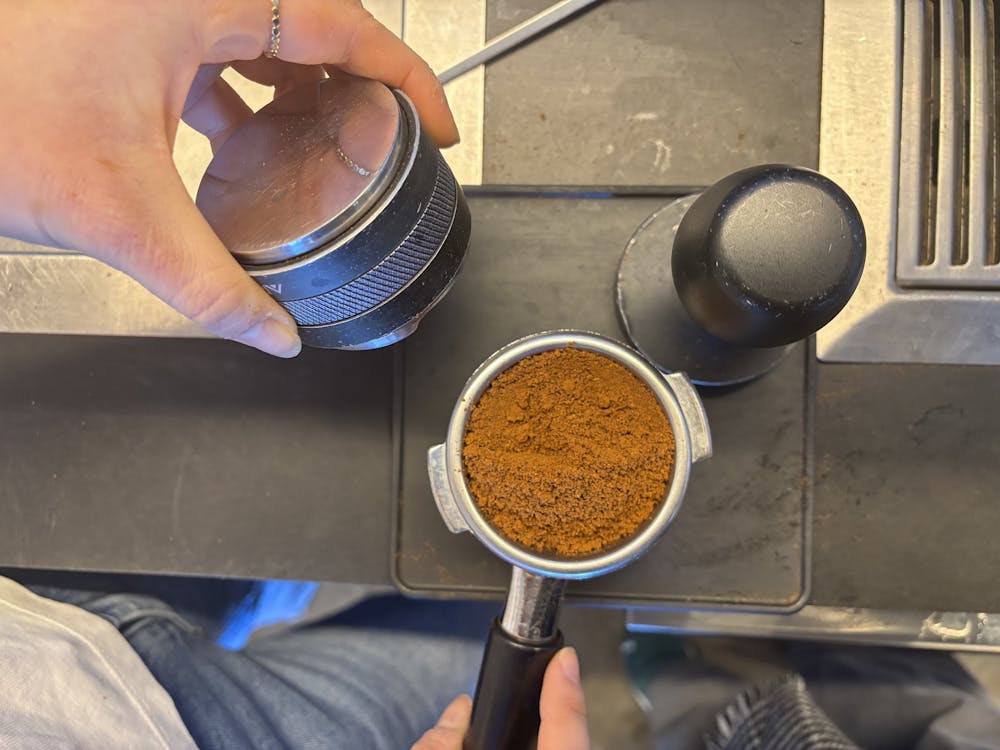

When making a customer’s coffee order, Coffee Club baristas prepare a “puck of grounds” for espresso, an evenly spread layer of coffee grounds filled into a portafilter. The even distribution of grounds ensures uniform water flow and resistance, optimizing flavor extraction from the grounds. When water channels through the puck of grounds, the espresso shot is created.

S.C.R.A.P. Lab buckets holding three and a half gallons of coffee grounds at the New College West branch of Coffee Club.

Allison Jiang / The Daily Princetonian

Managing the hefty weight of the buckets of coffee grounds has become a student job position with the Office of Sustainability. Talt referred to the student workers endearingly as “compost concierges,” whose work collecting compost materials spans across Robertson Hall, the International Food Co-op, as well as the Coffee Club locations.

Cade Hemond ’28 is one such compost concierge. On a Monday afternoon, I tagged along on his shift, during which he grabbed the keys to the Office of Sustainability van and drove along a route of campus locations to pick up compost buckets.

“When I was in high school, I led some initiatives with composting locally,” said Hemond, about why he applied for the job. “They were looking for someone who had a [driver’s] license and could carry compost buckets.”

Hemond first drove to NCW Coffee Club, where we collected compost bins full of coffee grounds. Afterward, we loaded the buckets into the trunk.

The compost generated from Coffee Club and dining hall waste is handed off to the S.C.R.A.P. lab to be processed. Then, the campus grounds team handles sanitation and brings raw materials in for compost.

Coffee grounds are especially useful in the composting process due to their fine structure, which can help aerate and improve compost drainage. Coffee grounds are also nitrogen-rich with a good moisture content and particle size, according to Talt.

“It’s kind of like making a cake — any recipe where you need to balance ingredients to have a thriving microorganism population,” said Talt. “When you build a recipe for composting, you want proper carbon and nitrogen ratios.”

Compared with coffee grounds, food waste is higher in nitrogen content, which must be balanced out with a carbon-rich material. While inedibles such as coffee grounds, avocado pits, and prep trimmings can easily be taken into the system, fats, oils, and grease within cooked food in dining hall waste can present problems of odor and impact the moisture content.

“It is interesting thinking about the different types of waste that we produce and how we manage that,” said Hemond. “My job at S.C.R.A.P. lab is very much focused on carbon-dense food waste, like the coffee grounds, whereas the dining hall waste [has] all kinds of stuff in there. So, the processing can be quite different.”

The S.C.R.A.P. lab also has to contend with non-compostables being placed in compost bins, an issue that Talt said has been on the rise. In the Fall 2024 semester, the Frist Center compostables bin had an average nine percent contamination rate, according to data from the S.C.R.A.P. Lab sent to the ‘Prince’ by Talt. In early February of the Spring 2025 semester, that rate had risen to 13 percent.

Some of the compost then goes back to campus to be used for planting.

“We’ll take the compost for our soil-making yard, and we’ll utilize compost as part of our soil amendment to make all our planting soil,” said Robert Staudt, assistant director for Campus Grounds at Princeton University.

“I would think that maybe some students are like, ‘Is it really going someplace?’” said Staudt. “It’s hard to see, but that cup [of coffee] is now all of a sudden this nice, rich brown soil over here. You don't necessarily equate the two, but it does happen over a couple weeks or months.”

Allison Jiang is a contributing Features writer for the ‘Prince.’

Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.