Lea en español aquí.

It is a quiet Tuesday night. The room is filled with red light, cold air, and low murmurs of attendees lined up in anticipation of their chance to look. Above, an expanse spanning the domed ceiling’s diameter previews the sights ahead: the lights of the sky.

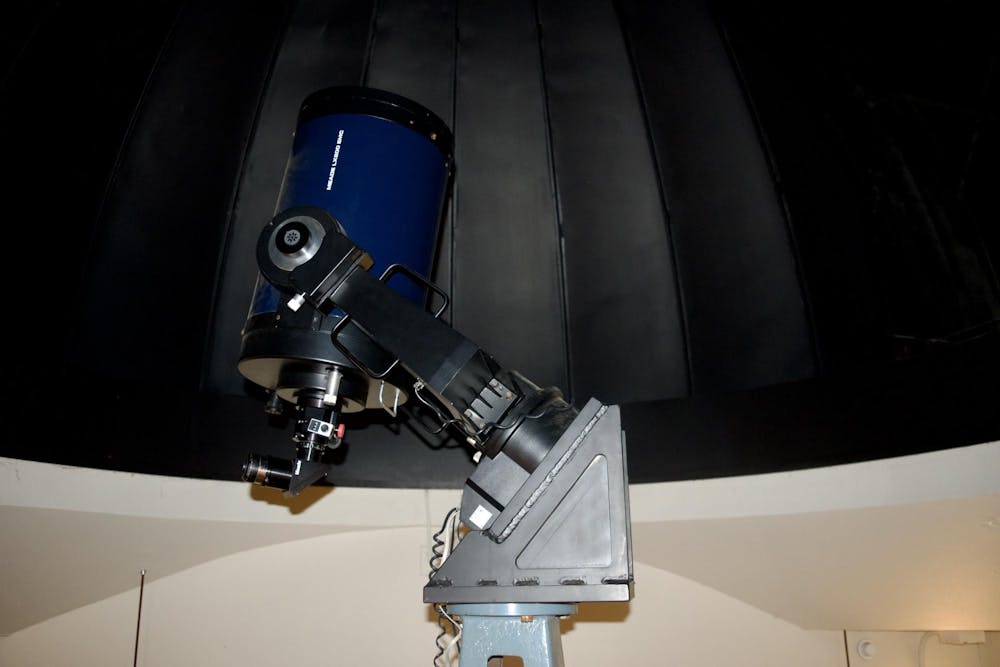

This room — the observatory at Peyton Hall — is just one of several spaces where the Princeton community turns its eyes to the stars.

Weather permitting, the observatory is open to the public once a month. Camryn Phillips GS organizes and promotes the showcases, directing fellow astrophysics graduate students and postdocs who volunteer to usher visitors, operate the telescope, and answer questions about the night’s viewings.

Phillips, who has engaged in science outreach since high school, is upfront: looking through the telescope at deeper-sky objects can require a leap of faith. “It’s this fuzzy blob, and you just have to trust that this little fuzzy blob is something cool, right?”

“[But] it’s still more than a lot of people have ever seen,” Phillips noted. “You can’t see it with just looking at the sky. You need a telescope for it.”

Ann Zhou GS described seeing Saturn through the telescope for the first time as “mind blowing.”

For community member John O’Connor and his kids, one time was not enough. “It’s one of our favorite things,” he said. “[The kids] look forward to it every month.”

The enthusiasm goes both ways. Charlotte Ward, a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Astrophysics who volunteers at the public observing nights, said, “When we get to just look at our local solar system, our local neighborhood, with people who don’t get to look at that every day, it reminds us how cool [our work] is.”

Phillips and their colleagues aim to connect the dots for visitors. “Oftentimes people have questions that I will try to tie to whatever we’re looking at,” Phillips explained. For example, while looking at Andromeda: “If someone asks me, ‘How do stars die?’ then I can talk about how Andromeda was the first galaxy that we saw individual stars in, and one of the ways we can figure out distances to the other galaxies is by stars going into supernova and dying.”

In fact, for Phillips, answering questions is a key part of the night. They said, “A lot of us are terrified of looking like idiots and asking stupid questions… [but] curiosity is the best thing you can do.”

“I think kind of the best response is, ‘Oh, that’s fascinating,’” said Phillips. “I always hope that I can give them some information that they really enjoy or can walk away with. And I try to explain it in such a way that, when they repeat it, it’s not too factually incorrect,” they added with a laugh.

Phillips views this as a scientist’s responsibility: “Science is useless if you don’t tell it to other people… One of the moral things as a scientist is, you do research and then you tell it to other people.”

The Amateur Astronomers Association of Princeton (AAAP) likewise uses Peyton Hall to expand access to astronomy education.

On the second Tuesday of each month, September through May, AAAP holds meetings which are open to the public — including Princeton students, community members, and Zoom attendees. Many lectures are also recorded and made available online.

The first half of each meeting features a lecture from a professional in the field. The second is dedicated to hands-on astronomy — the “nuts and bolts of optics and cool stuff that’s going on in the science,” said AAAP Director Rex Parker. Parker also encourages members to participate in what he calls “un-journaling,” in which someone presents on a journal article, a trip, or something they’ve read in a publication like Sky and Telescope (which Parker calls the “bible of amateur astronomy”).

On the fourth Tuesday of each month, AAAP hosts meetings for a subgroup dedicated to the technology and techniques of astroimaging — capturing and processing images of the skies. For Parker, astronomy's overlap with real-world technology is one of the discipline’s strengths. “Even though it’s a very esoteric science, it sort of blends into all the other things that are going out there — computer technology and software and physics and energy and all the other things that people are interested in.”

Parker himself came to his passion for astronomy from a career in biochemistry. “When I turned 40, my wife bought me a Celestron telescope, and that kind of changed my life. We joke about [how] some guys have their midlife crisis and get the red sports car — but I got the telescope. So I started doing real astronomy.”

Parker and his wife even moved from Lawrenceville out to Titusville, which rests along the Delaware River, in pursuit of darker skies. Parker now does astrophotography from his backyard, which he posts on his personal website.

Through AAAP, Parker helps facilitate the observation experience for others. In addition to its monthly club meetings, AAAP hosts viewing parties at schools and scout troop events as well as public observing nights at its observatory in Washington Crossing State Park.

The AAAP observatory is open to the public every Friday night, April through October, if conditions are at least partly clear.

According to Parker, the group has “concentrated on equipment that can break through the light pollution” that “robs the sky of contrast” in the area.

In fact, Parker is calling for action to reduce the barrier that light pollution poses to broader observing. Parker sees the night sky as one way to get kids excited about science — but, according to him, “a kid growing up in Trenton looking up is not going to be inspired by the night sky. That’s a problem of our days.”

People viewing the night sky through the Peyton Hall telescope on a Tuesday night.

Helena Richardson / The Daily Princetonian

To that end, Parker described, he joined the Hopewell Township local government’s environmental commission and helped create their first outdoor lighting ordinance.

“I think it’s really a consciousness-raising thing,” said Parker. “If more people began to realize that we could get rid of three quarters of the lights that are across our country — that we’d be equally safe, and we could all see the sky — we could get to that point, but we’re a long ways away right now.”

In the meantime, AAAP will keep looking at what it can.

Bob Vanderbei, AAAP Associate Director and Professor Emeritus in Princeton’s Operations Research and Financial Engineering Department, is proof of AAAP’s reach. After Vanderbei began teaching an introductory computer course at Princeton in 1999, he noticed an astrophotography calendar on the office wall of the computer lab’s tech manager. That manager was none other than Kirk Alexander, then-Director of AAAP. At Alexander’s invitation, Vanderbei attended an observing event — and he was hooked.

Like Parker, Vanderbei runs a website for the astrophotography he does from his backyard. While he may photograph things more than once, supernovas and variable stars keep things interesting. Through his work, Vanderbei has tracked change over time.

Vanderbei has also co-authored Sizing Up the Universe: The Cosmos in Perspective and New York Times Bestseller Welcome to the Universe in 3D: A Visual Tour. In addition, he teaches a freshman seminar on “Sizing Up the Universe.” He shared with the ‘Prince’ that the course was preparing to welcome Neil DeGrasse Tyson for a guest lecture on questions regarding extraterrestrial life the following day.

Princeton students interested in engaging with amateur astronomy also have the opportunity to do so with Princeton Astronomy Club (PAC). According to PAC treasurer Aryan Gupta ’27, the club hosts events around twice a month, ranging from guest lectures in Peyton Hall, to space-themed study breaks, to star parties with telescopes in the Forbes backyard.

Gupta recalled pointing out certain constellations to a friend at a star party and then watching the friend passing on the information to others. “It was really cool — people were taking an active stake in it,” said Gupta.

More generally, the attendance at star parties tells Gupta “that people really do care about just coming out and seeing the night sky for the sake of loving astronomy and learning more — and just looking up.”

Like Phillips, Gupta has been involved in science outreach since high school, and like Parker and Vanderbei, Gupta uploads his astrophotography online. They are united by their belief in the capacity of the stars to inspire.

“Astronomy is really special in the sense that you can do science outreach and talk about these ideas — planets, galaxies, [...] huge gas clouds, or if other worlds of aliens exist — and kids can comprehend that in their mind. The public can comprehend it in their mind,” commented Gupta. “And they'll naturally draw a fascination or curiosity towards it.”

“I think that's a real gift that astronomy has,” said Gupta. “You'll bring out a telescope, you show it to people, and they can instantly look and do something.”

To Parker, that instant look is powerful. “There’s something about the experience of photons from millions of light years away — or at least thousands of light years, depending on the object — striking your retina. There is a physical, biological exchange going on there that connects you with the universe that’s really profound.”

Helena Richardson is a staff Features writer for the ‘Prince.’

Features contributor Katie Thiers contributed reporting.

Please direct corrections requests to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.