College activism is not dead.

This was what a reporter for The Daily Princetonian wrote in a 1998 article covering the revival of Princeton‘s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that year. Once a lively group on campus, the chapter had dwindled due to low membership. Since the early 1990s, chapter members have advocated for civil rights and justice on campus, from petition drives to social protests. However, ebbs and flows in membership have made it difficult for the chapter to retain leadership in the last decade.

Just as Princetonians united over twenty years ago to reawaken campus activism, students like Chris-Tina Middlebrooks ’27 have made it their mission to reactivate a community that bridges belonging and social change.

“I’m the secretary for the NAACP New Jersey State Conference Youth and College Division. We always say that wherever we’re going to school, if there’s not an NAACP, we’re making one,” Middlebrooks explained to the ‘Prince.’

The NAACP was founded in 1909 by civil rights activists, including W.E.B. DuBois and Ida B. Wells. The organization advocates for the political, educational, and racial equality of all people of color, specifically Black lives, in the United States. A main initiative of the NAACP is to mobilize young leaders to champion social justice. Their college chapters enable students to develop skills in collaboration and leadership and participate in social and political activism.

The NAACP Princeton chapter is set to recommence programming this spring after a period of inactivity, with 36 members and an official executive committee, according to Middlebrooks. Her revival of the chapter aims to honor generations of Black women that paved the way for the NAACP.

Owen Garrick ’90 established the Princeton NAACP chapter during his junior year to increase student engagement in national and local issues. There were several other Black campus groups, like the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE) and the Organization for Black Unity (OBU), but Garrick was interested in the NAACP because the organization created a civic network for students.

“I believe we were successful in getting students, particularly Black students, to consider what solutions we could begin to bring to bear for them,” Garrick said.

Garrick organized initiatives in support of economic development within Black communities. For example, the chapter advocated for local neighborhoods to maintain Black homeownership and hosted financial literacy workshops to help students manage credit card debt.

Garrick’s goal was for the NAACP to be a vehicle for education and social impact, which motivated more student leaders to take action, including Dr. Karen Jackson-Weaver ’94, the first woman president of the University chapter.

“I had a deep love and affinity for the work of the NAACP, as well as for all the members of the Princeton University chapter,” Jackson-Weaver noted.

Dr. Jackson-Weaver became an active member of the NAACP during high school. She participated in many Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific (ACT-SO) competitions hosted by the NAACP at the national and local level.

“I had very fond experiences and memories of youth and leadership development and social activism in high school that were very impactful. So when I transitioned to my undergraduate studies at Princeton, I was super thrilled to see the NAACP,” she explained.

Similar to Garrick and his involvement in PU-NAACP, Dr. Jackson-Weaver was passionate about amplifying issues on and off campus. During the dynamic political era of the 1990s, she met with fellow officers every week to discuss and debate national and global events, which would shape their campus efforts.

Jackson-Weaver described, for instance, how the NAACP organized a campus-wide Haitian relief fast to raise funds that would combat the nation’s political and economic instability in the early 1990s. The initiative encouraged students to become involved in a global effort. Students who participated in the fast did not eat dinner for one night and donated the money they would have used for dinner to the fundraiser.

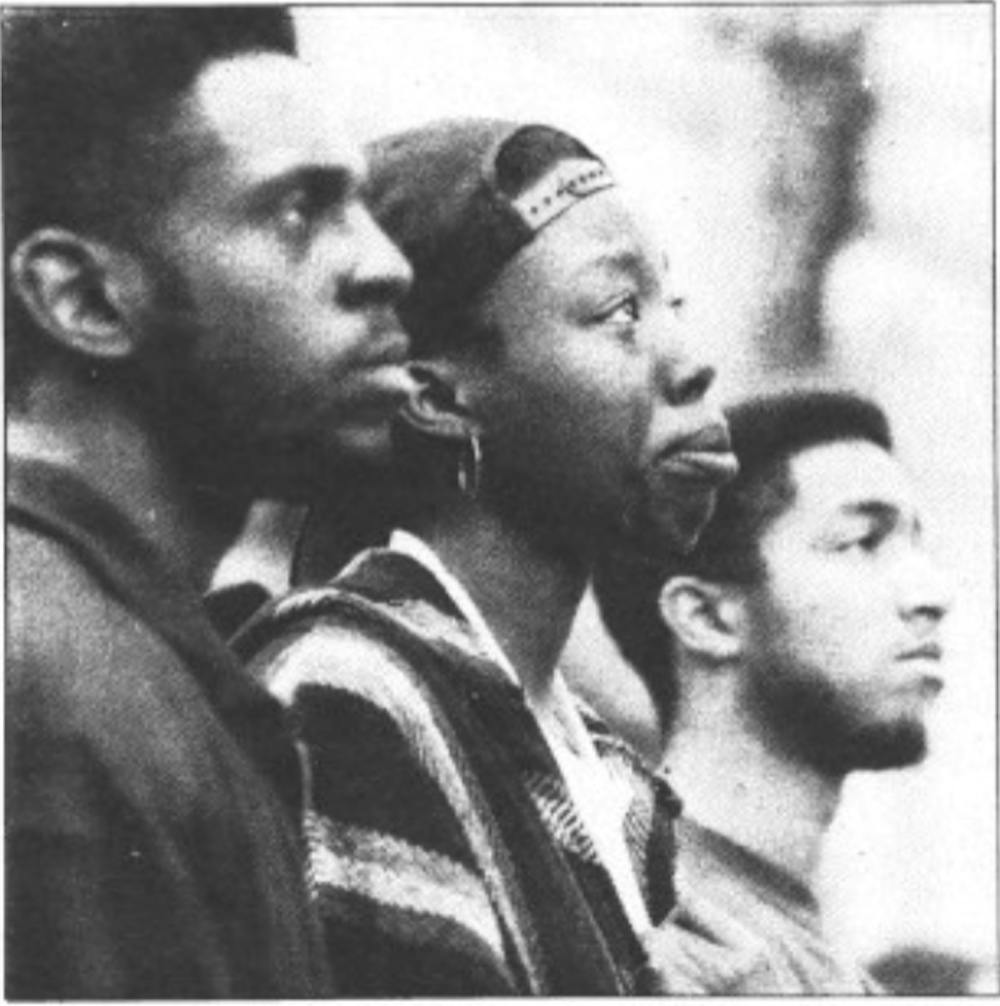

The NAACP also advocated for ending police brutality, particularly after the not-guilty verdict of the 1992 Rodney King case. In 1991, Rodney King, an African American man, was critically beaten by four officers of the Los Angeles Police Department after a high-speed pursuit. As riots erupted across the country, Jackson-Weaver coordinated with other campus groups to host a rally to protest the police officers’ acquittal. The event occurred in Firestone Plaza to centralize social activism on campus. Students, faculty, staff, and even student leaders from the Princeton Seminary united to bring attention toward inequality and racism in the United States.

“We were asking the institution to really be serious about interrogating not just race and what it meant socially as a student of color, but also what it meant in terms of the curriculum, faculty, and staff representation and undoing decades, even centuries of institutional racism,” said Dr. Jackson-Weaver.

Events like the Haitian relief fast and the Rodney King rally further encouraged a wave of determination amongst Black women in the chapter.

In 1998, Misha Charles ’01 reinitiated Princeton’s chapter of the NAACP after the group became inactive due to low membership. As president, she petitioned for the University to create a department of African languages. The NAACP gained 622 signatures from students, along with endorsements by faculty members in support of their proposal. Although Princeton established a program in African Studies in 1975, it remains the only Ivy League institution that does not offer a major in the discipline for undergraduate students.

By the late 2000s, the University chapter had disbanded once again until student Paige Floyd, who studied at Princeton from 2006 to 2008, recruited over 200 students to revive the NAACP’s presence on campus. She worked with Dr. Jackson-Weaver, the Associate Dean of Academic Affairs and Diversity at the time, to strategize methods to improve inclusion and social activism on campus.

“I wanted to be a mentor, someone who could help them leverage the initiatives and the work that they were doing in a way that would translate into their career path,” Jackson-Weaver added.

“It [the NAACP] really helped me to develop my personal skill set. It also helped me have a sense of pride in my heritage and connect with people from all across the country,” said Floyd.

Despite challenges to maintain PU-NAACP’s activity over time, Middlebrooks desires to carry on the torch of her predecessors. She hopes to foster collaboration between students and the local community and organize initiatives for professional development and scholarship displacement (where receiving third-party scholarships results in a reduction of financial aid).

“The NAACP gives students a different kind of voice. It is an organization that empowers them,” she said.

Dr. Jackson-Weaver recognized women, particularly Black women’s vital contributions to civil rights efforts, despite historically being overshadowed by male leadership. She sees the Princeton NAACP as a way to recognize their history and ensure that it is never forgotten.

“Women get things done. We make the community better, we make the world better, and we don’t do so looking for a spotlight. We do it because we care and we want to make a difference,” Jackson-Weaver said.

As the University chapter of the NAACP prepares to make a formal return this upcoming semester, Middlebrooks and fellow officers seek to continue the work of past generations by advancing the interests and rights of all students.

“It is a continuation of women’s leadership that has always existed but has been obscured,” Jackson-Weaver noted. “I’m excited for the work that they’re going to do, and they’re building on a wonderful legacy.”

Synai Ferrell is a staff Features writer and staff Podcast writer at the ‘Prince.’

Please direct any corrections requests to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.