Have you ever wondered what chickens talk about? Edward “Ted” Borer has, and through the careful study of his own backyard hens, he has pinned down three words in chicken: a calm good morning cluck, a past-tense verb for having laid an egg, and an alarming squawk that means trouble. As a dedicated gardener and chicken-caretaker, Borer placed a quote by the Dalai Lama above his coop, as well as a Tibetan prayer flag and a federal cross, to playfully encourage peace and compassion among the rowdy flock. He also keeps a live camera trained on the coop. “I’m an engineer,” he said, “What did you expect?”

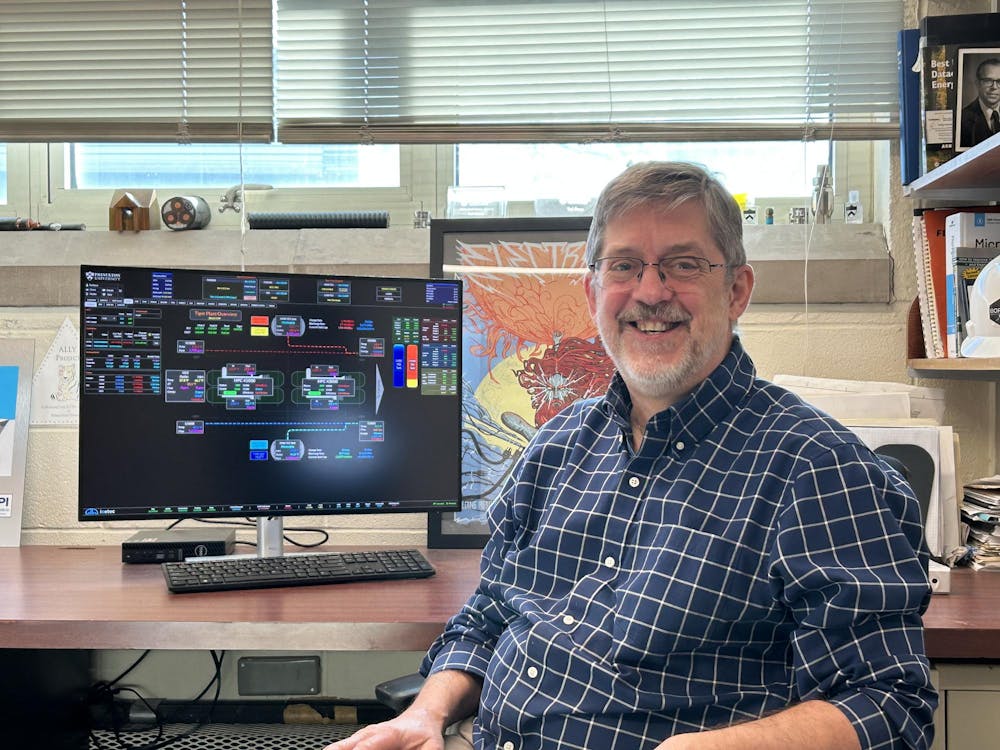

Borer is not just any engineer. Until recently, he was Princeton’s own Energy Plant Director, overseeing the Princeton Energy Plant, and more recently, the two new geo-exchange facilities: the Thermally Integrated Geo-Exchange Resource (TIGER) and Central Utility Building (CUB). After 30 years of stewarding Princeton’s energy, Borer retired on Jan. 3 and is now embarking on a new chapter of his life as a part-time private energy consultant. David Weis, who started working as a contractor at the Energy Plant in 2005 and officially joined the Princeton staff as an Energy Plant Controls Engineer in 2023, recently stepped into the director role.

Throughout his time at Princeton, Borer has extensively shared knowledge of the systems tucked at the edges of campus and buried hundreds of feet underground, with both Princeton and non-Princeton audiences. He has given TIGER Talks, delivered guest lectures, helped advise student theses, provided U.S. Senate briefings, and was featured in a New York Times piece on U.S. colleges implementing geo-exchange. All the while, he has been leading the team that keeps Princeton’s power on and the geo-exchange transition running smoothly behind the scenes. The Daily Princetonian recently sat down with Borer in his photo-adorned MacMillan Building office to learn more about his life: past, present, and future. Unsurprisingly, energy was a recurring theme.

For Borer, it all started with LEGOs. “LEGO blocks, tinker toys, erector sets, treehouses, train sets,” he said, rattling off his childhood pastimes. “I had this visceral need to take things apart, understand how they work, build stuff, work with my hands. I was sitting there building stuff out of LEGO blocks before kindergarten. I just need to.”

Despite his innate fascination with machinery, Borer explained that the mathematical theory behind it did not come easily for him. “I suffered through every math class from second grade on. I mean, I was not a good math student,” he said. Borer described himself as an “experiential learner,” explaining, “Once I learned each thing, I loved learning it as a tool.”

At first, college presented the same academic challenges, but that changed when Borer’s father helped him secure a job at a Philadelphia Electric Company power plant. The reality of the power plant did not match the theory he was learning in school. “You get to a real power plant, and it’s crazy hot, and you’re sweating and dripping, and covered with coal dust,” he said.

But this did not deter him; instead, seeing the real deal inspired him to continue with his degree. “I remember driving [to the plant] one time at night and seeing, oh man, this is where all the power for the whole city, the whole region is coming from … I remember that one moment, thinking, ‘this is pretty cool,’ and getting excited,” he said.

After that experience and a quippy lecture from his dad, Borer’s grades improved. “I think the main motivation was finally doing something where I could see the effort I was putting into school, and the reward of getting to actually play with these things,” he explained. “For me, a lot of this is just joy, it’s just playing. It takes a lot of work, playing, but it’s fun.”

The pictures adorning one wall of Borer’s office provide a visual archive of his early work experience in the energy industry. “The [photo on] the far right is a coal-fired power plant,” he said, pointing at the image. That plant also had a steam turbine generator. “I loved working with those guys. It was really fun, and challenging,” he added.

Photographs of energy plants and machinery on Borer’s office wall.

Courtesy of Raphaela Gold '26.

Borer also spent a couple of years working in nuclear energy. This involved converting energy from coal to natural gas, which was similar to Princeton’s energy landscape when Borer arrived on the scene in 1994.

At the time, Borer was a project manager for the construction of the cogeneration plant, which has been heating and cooling campus through the combustion of natural gas since 1996. Since then, he has seen Princeton through the early stages of its transition to geo-exchange. This will become the University’s primary energy system over the course of the next decade, and according to Borer, it already powers around 17 percent of campus buildings — much more efficiently than the cogeneration system.

“I’m super proud of helping to plan the path to carbon neutrality,” said Borer. “I grew tremendously by overseeing the construction of the cogen plant. I grew a lot from overseeing the construction of the double storage plant, and then being involved in the leadership … of these expanding energy plants and planning out 10, 30, 50, 100 years of energy future,” he continued.

Borer also noted the importance of being part of Princeton’s “community of thought,” which he appreciates for encouraging everyone to pursue their passions. For example, in 2019, Borer had the idea of leading a 21-day plant-based experience for students, professors, and staff. He had switched to a plant-based diet for health reasons, and wanted to bring people together to discuss it. The program featured a range of speakers, from a farmer to religious leaders to dietitians.

Borer reflected that even though the project “had nothing to do with engineering, [it was] all to do with being part of a community of thought, and Princeton being open to ‘Hey, you wanna try something? We could do that.’ And I was blown away.”

When asked how he feels about leaving Princeton, Borer said, “Super emotional, like every emotion.” He is already anticipating the loss of making daily small talk with his colleagues. “I’m already grieving not having these hallway conversations,” he said.

Borer, in turn, will be missed by his coworkers. Princeton Energy Plant’s Chief Engineer Eric Wachtman, also soon to retire, has worked at Princeton for 33 years and remembers working with Borer in their early days as operator and project engineer respectively. “As you can tell, Ted is extremely proud of what he does, and cares about what he does, and he loves to talk about what he does,” said Wachtman. “He’s one of the most passionate men about energy, what he did, and what he provided for the University that I’ve ever met.”

One thing Wachtman will not miss one bit is driving with Borer at the wheel. At Borer’s retirement gathering, Wachtman recounted an anecdote about the stressful experience of the time Borer drove the two of them to check out a new gadget. “He’s a terrible driver, but he can ride a bike. I would never get in a car on the passenger side with him ever again, but I would get on the back of a bicycle with him,” he said.

Weis, who has recently become Director of Campus Plant, said of Borer, “He has this infectious enthusiasm and a willingness to try new ideas … I’ll miss that a lot.”

Weis hopes to emulate Borer’s quality of conveying difficult scientific concepts in an accessible way to all audiences. “What really shines out … is how he communicates with whoever he’s talking with: He will meet whoever they are where they are,” he said.

Now that TIGER is up and running, one of Weis’s goals is to leverage the data and knowledge the team has already collected to further optimize the plant. “There might be ways we can do things a little differently, or do things at different times of the day or times of the season in order to increase the overall performance and efficiency,” he explained.

Borer noted that Weis’s experience is well oriented toward the future of the plant. “Dave brings a more appropriate skill set for today’s and tomorrow’s than I do for today’s and tomorrow’s. My match has been better in building the cogen plant and operating. I’m totally celebrating who Princeton picked,” he said.

So, what exactly will Borer be getting up to outside the gates? He plans to serve as an expert advisor through his own company, helping other people accomplish what Princeton has accomplished at many different scales. “I think ‘calling’ is a little bit audacious, but I feel compelled to go out and continue this kind of work,” he said.

This means working with institutions of all sorts, from military bases to airports to college campuses, who aspire to reduce their carbon footprints but may not have Princeton’s level of engineering or financial resources. “I can … basically hold your hand through this process. Princeton stepped on these stones to get across the creek. This one’s a little wobbly, that one’s sharp, that one’s slippery, but I can help you get across the creek,” explained Borer.

But working 10–20, rather than 40–60, hours a week will give Borer some spare time to fill with his plethora of hobbies. “I aspire to challenge myself. What percentage of the food I eat in a year can I get out of my own garden?”

Borer and his wife enjoy gardening and canning the fruits of their labor to give away as jam over the holidays. Naturally, Borer also uses canning as a metaphor when he describes geo-exchange to non-engineers. He is also an avid cyclist, with over 100,000 miles of bicycling behind him, mostly from commuting to and from work, and he is striving for even more now. And, as the father of four children all of whom are in college or beyond, Borer is looking forward to spending more time with his wife and adventuring together.

Borer also hopes to engage in unpaid service work through his church, which periodically leads trips to build water purification systems in impoverished areas of Mexico that lack clean water. To prepare, he studies Spanish on Duolingo daily in the hopes of having interesting conversations while volunteering.

Over the last year, as Borer has been meditating on what to do next, he landed on a succinct morsel of wisdom for himself and others, “Each of us should say: What am I any good at? What does the world need? And what do I enjoy? And try to seek the center of that. Because if any one of those components isn’t there, you could do better.”

Raphaela Gold is a head Features editor for the ‘Prince.’ Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.