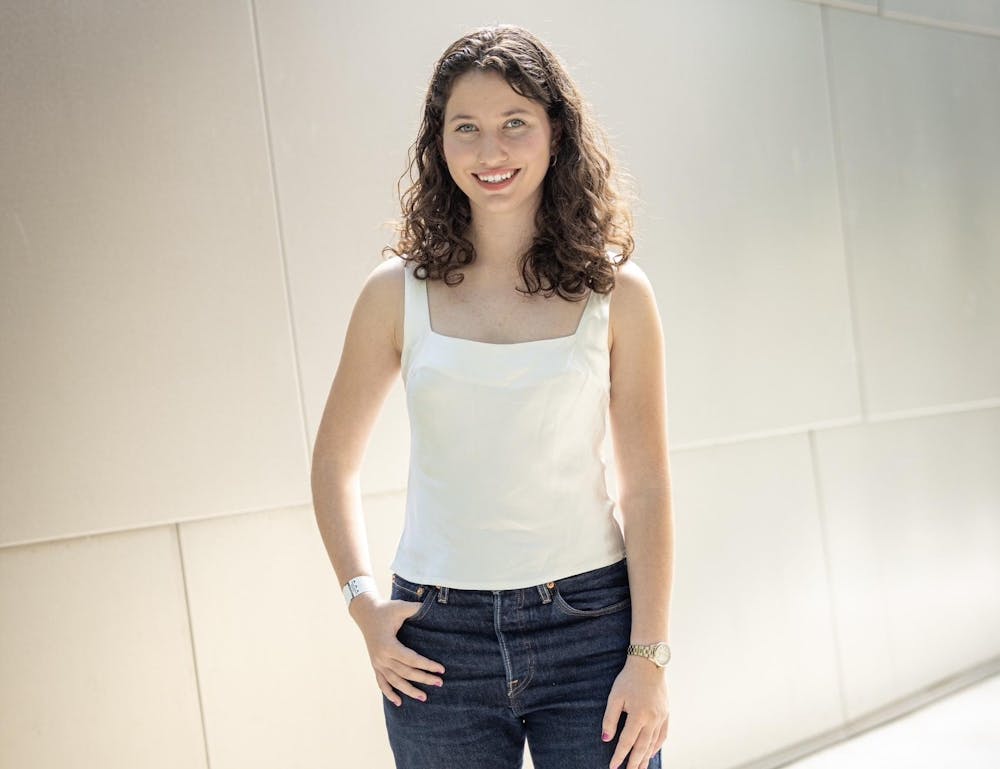

Dim sunlight illuminates the halls of the Effron Music Building on a sleepy Monday afternoon. Up two flights of stairs is a musician’s tree house and a hall of practice rooms lined with wooden floors, accompanied by faint sounds of music. In one of these rooms, Marvel Jem Roth, a composer and first-year Princeton student, settles naturally on the piano bench to speak about music and composition.

A budding composer from Los Angeles, Roth has worked with and composed for the Colburn Youth Ensemble, Luna Composition Lab, National Youth Orchestra, and the LA Philharmonic. Her work has been performed by the Kronos Quartet, among others, and she herself has performed in the orchestra under the direction of famous conductor Gustavo Dudamel during World Orchestra Week.

The Daily Princetonian sat down to discuss her work in composition.

This interview was edited for clarity and concision.

Daily Princetonian: Tell me about your path to composing. How did you start out; where are you now?

Marvel Jem Roth: I started playing piano when I was four years old, and I loved it, and then I reached a point where I was practicing, and I kept being told “you’re really good, but you’re not perfect.’” That drove me crazy when I was young, because I wanted to be perfect, and I was so frustrated with that notion that I started to dislike music. So instead of playing like Bach fugues, I started improvising — what was my idea of “perfect” in music? Of course, these were not perfect improvisations, but it was kind of just me finding music as more of a self expression.

Eventually I found composition. I was in a program called the LA Phil Composer Fellowship Program, and they took about 15 young composers in high school, mostly seniors, and I was fortunate to be selected as a sophomore, so I got to take the program for three years. I got to write for the LA Phil and a lot of musicians in the LA area. My final project was for the LA Master Chorale, and they really taught me how to notate and express myself clearly, and what the side of perfect composition is, which isn’t necessarily the ideas, but how you communicate on paper. I really fell in love with that art of engraving, or notating. Since then, I’ve gotten to do some pretty cool things. I love composition. I’m still studying it here.

DP: What is it like seeing your work performed and hearing it come to life?

MJR: It’s so many emotions. I’m always scared, I’m always excited. There’s always an acceleration to it, because a lot of composers write with something called playback, which is like MIDI that works in your notation software like Sibelius or Dorico and you can kind of hear a computerized version of music. I don’t listen to playback when I compose, so everything is purely kind of how I imagine it, or how I’ve written it on paper, or what I’ve played on piano when I’m starting to come up with concepts. So hearing notes out loud for the first time, especially writing for orchestra, there’s so many components and so many colors. It’s really overwhelming, but it’s really beautiful. I think the orchestra is one of the most magical things we have. There’s all these components behind stage; there’s librarians, managers, conductors, and there’s such a bureaucracy to the orchestra in a beautiful way. To hear music out loud, at the end, I’m always so grateful.

DP: What’s your favorite ensemble to write for? Do you have a favorite genre or style?

MJR: Orchestra. Orchestra with choir is something I haven’t written, and I would love to. I’ve written them separately.

I mainly write classical music, contemporary classical. But I had training in Broadway, and I had training in jazz, so I have a lot of different genre qualities that come out in my music, especially my improv. That [improv] is something that is part of the classical tradition, but more so is thought of as a jazz tradition. I incorporate a lot of improvisation in my music.

DP: Do you have someone or something that you draw a lot of inspiration from?

MJR: I draw a lot of inspiration from who I’ve studied with. Andrew Norman, Thomas Koch, Sarah Gibson, who unfortunately, recently passed. She was one of my most inspirational mentors and a beautiful pianist, beautiful composer, such a giving person. More recently, I’ve studied with Angélica Negrón, who’s incredible, Ellen Reid, and now at Princeton, I’m in a course with Steve Mackey. I’m really loving his class

More specifically in what I’m writing, I write a lot about nature. Something I’ve been really interested in lately is distortion. I recently had a piece come out called “lens.” It was played by the Kronos quartet, and it was just played this Saturday at the LA Phil as part of the noon to midnight concert, which is incredible, and I’m so grateful. That piece is all about the natural and urban landscapes of Los Angeles and how media is able to distort those. I’m playing with distortion now in a piece I’m writing about fairy tales, the Bible and feminist perspective and how that gets distorted. I don’t like writing music about things. I like writing about my feelings about something. I write about my reactions to ecofeminism or my reactions to revolutions that went poorly. And I think those are all things that make my music a little bit more authentic.

DP: Where is your dream venue on campus to have one of your pieces performed?

MJR: Richardson. I was just there with the Piano Ensemble, and it’s such a beautiful space and so unique to Princeton.

DP: Agreed. What do you hope to convey when you’re composing a piece?

MJR: I hope to convey something about myself I didn’t know before I wrote it. I often find who I am when I’m writing. I wrote an orchestra piece called Rebounds. I realized that I was really going through so many changes in my life in such a short period of time, and the piece really ended up conveying that. I didn’t understand it until I heard the full orchestra playing it live that that’s really what I was writing about, not just the rebounds I was visualizing.

DP: So it’s like a process of self discovery.

MJR: Process of self discovery, yes.

DP: Could you walk me through the process of composing?

MJR: It’s different for everyone. I always write paper and pencil. I have a notebook that makes me look slightly insane; it has triangles and scratches and sine waves and lines and all kinds of, on the surface, very strange looking sketches, which each convey a different element of the music that I’m thinking of. When I don’t know where to start, I always start there, and then I go to short score, which is writing on staff, on paper and pencil, usually at the piano. I record myself improvising because improvising is how I started composing, and it’s very integral to my style. I sit at the piano and play things, and I go inside the piano and I pluck the strings, or I’ll bow the strings, just trying to get sounds. Then based on those sounds, I can notate.

When I compose, I think about the instruments first. So when I wrote a clarinet choir piece, I was very much thinking about the capability of the clarinet’s dynamics and the different ranges of the clarinet. Timbre is something I really think about, the process of how we’re going to shift timbres to store timbres, as I said, or how we’re going to really play with the instruments to make it more than just “this is a violin.”

Then I continue writing. Most composers can’t compose front to back. I very much compose front to back. I struggle to go in the other direction, because I find my pieces are so much about the development of things. Every now and then I start in the second minute, but I rarely start at the end. I can’t start at the end. I workshop with musicians, I do some revisions, and then it usually has a performance, if I’m fortunate.

I would say another massive part of my time composing is in the engraving and going in the computer, just making sure the musicians’ parts are beautiful, the score is beautiful, legible, clear, and really communicates everything I want, without me having to be there. My ideal piece is something that communicates everything, creatively and emotionally, but in a way that no questions are asked and we can really just make music without spending too much time deliberating things besides intention.

DP: How long is the composing process?

MJR: The quickest I’ve written a piece was a day. The longest it’s taken me is four months. It really depends on the size, on the scale.

DP: Anything else?

MJR: Thank you.

Annika Plunkett is a contributing writer for The Prospect and a member of the Newsletter team. She can be reached at ap3616@princeton.edu.