On Thursday, Nov. 7, the Princeton University Art Museum Student Advisory Board and members of the Princeton community gathered to welcome Shahzia Sikander, a MacArthur Prize-winning artist commissioned by the University in 2017 to create several works oscillating between glass and mosaic mediums. The exhibit is installed in the Julis Romo Rabinowitz Building.

According to the Princeton University Art Museum’s website, these installations of her work, a painting on glass entitled “Quintuplet Effect” and a sixty-six-foot-tall mosaic scroll called “Ecstasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector,” were her first large-scale public art commissions, though she spoke of other public art projects she has completed since. The pieces played on what Sikander describes as “the rhetoric of imagination [that] seems so much more buoyant” within a postcolonial context. The visual possibilities are both freed from previous restraint and acknowledging the universality of the imagination itself, an especially relevant theme for a building that houses both the University’s international programs and its Department of Economics.

In the first leg of the talk, Sikander took to a podium and guided the audience through a series of photos of her body of work over time, infusing context into her installations at Princeton and explaining how much of her work strives to center female narratives. One piece with a strikingly memorable story, she explained, was her sculpture entitled “Witness,” a large golden female form with a wide metal skirt decorated with mosaics, but open, visually incorporating the surrounding landscape. Its hair curled back in braided tendrils that Sikander described as symbolizing “strength and wisdom,” while its arms, connecting back into the body, represented “resilience … autonomy, [and] carrying roots wherever you go,” and how women are “connected through memories, stories, collective consciousness,” particularly immigrant women.

Sikander walked the audience through the previous iterations of the project. In its initial location of installation, Madison Square Garden in New York City, the sculpture’s face looked out proudly, but when “Witness” moved to the University of Houston, it faced a different fate. There, it was beheaded in the middle of the night; the piece had been deemed satanic by its vandals. Sikander offered in response that “instead of censoring or destroying art” we should “embrace its ability to challenge our perspectives, to see beyond binaries, to engage with the complexities of identity” and “the right for women to be heard and seen.”

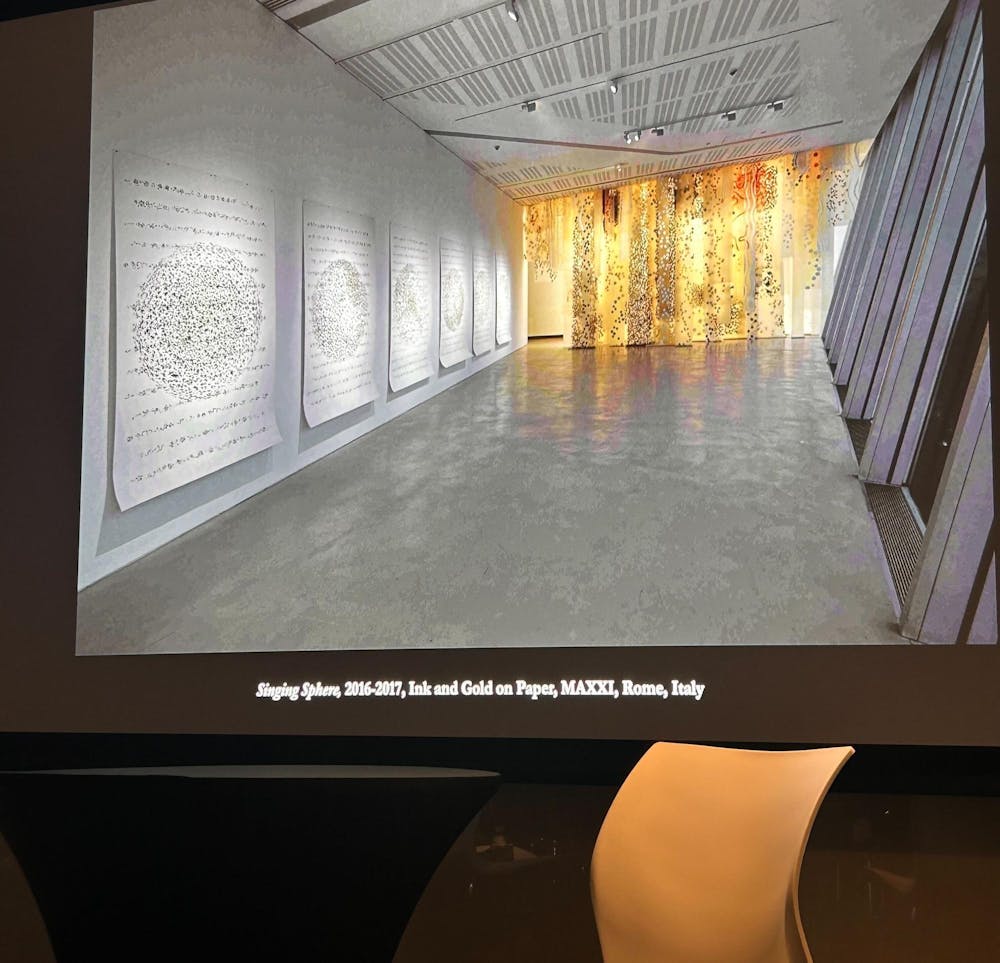

Another work Sikander focused on during the discussion was her “Singing Spheres.” In her construction of the spheres, she linked her use of “ink with oil, oil with movement, movement with time, time with history, [and] history with hierarchy.” She described how the spheres, in all their movement, represented the “feminine form” and “its redemptive power, almost as a counter to global capital” as well as the hierarchies and histories she previously noted.

In the second half of the talk, Sikander sat down with James Steward, Director of the Princeton University Art Museum. When asked about the “question of indigeneity” in her practice and training as an artist as a Pakistani-American visual artist, Sikander responded by saying “in terms of [her] background of learning manuscript painting…there should not be a fetish about what that is,” and resisted the idea, informed by colonial legacy, that the “language of artists” in Pakistan can be diminished to one specific form. Other forms, she explained, such as the abstract expressionism that makes its way into much of Sikander’s work, were also prevalent in Pakistan during the time of her artistic training.

As the talk came to a close, Sikander further emphasized this point by discussing who decides what is considered indigenous in the context of how history is told and retold from the perspectives of those holding power. The stories we understand about art history and history more generally, she said, are “embedded in the histories of [who was] the highest bidder,” but deconstructing colonial narratives, even repurposing them, “is where the creativity lies.”

Emma Cinocca is a member of the Class of 2027 and a staff writer for The Prospect. She can be reached at emmacinocca@princeton.edu.