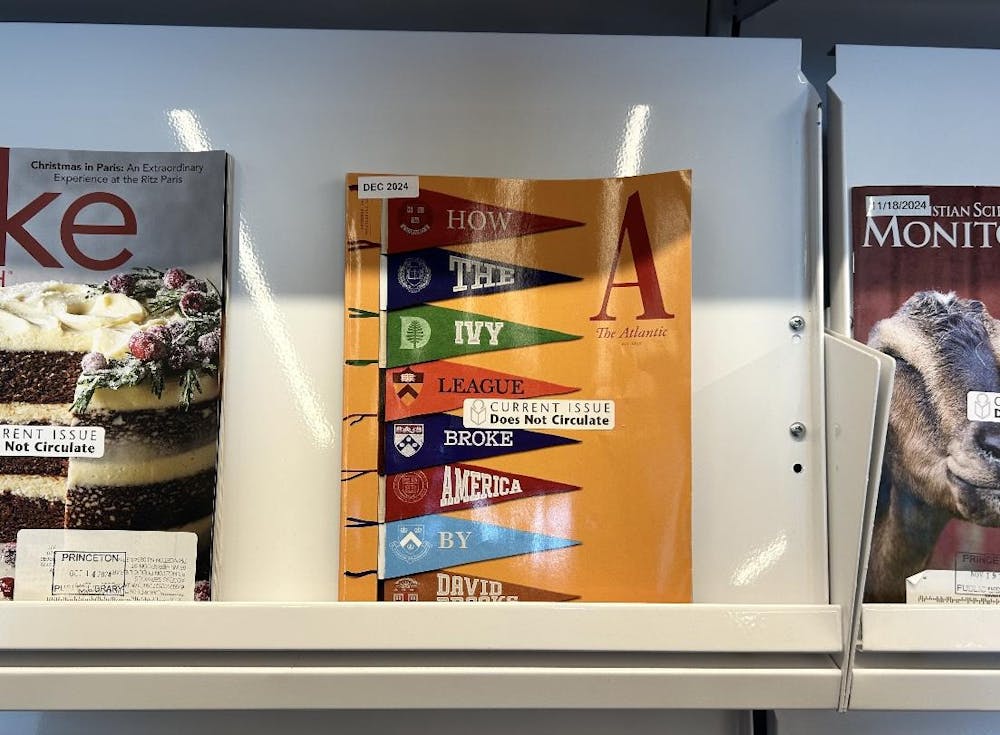

Author David Brooks recently took to The Atlantic to offer his explanation of how Ivies like Princeton “broke America,” describing these schools as the power centers of the elite class. Brooks levels his argument against the supposed “meritocracy” of American higher education by describing the six “sins” of the Ivy League. He puts forth the claim that elite college admissions overrate rigged metrics of intelligence and, consequently, they produce a generational caste system with a class of elites who believe themselves superior but are often unsuccessful.

Brooks’ argument has its merits, but ultimately it falls critically short. There’s a seventh sin of American meritocracy that Brooks overlooks, and it’s the most deadly one: because of pervasive inequity, meritocracy in America is and always will be an illusion. Brooks proposes an alternative set of criteria which he claims would fix American meritocracy, yet he fails to see that the issue lies in the country, not the system. Brooks is mistaken when he claims the Ivy League “broke America;” America has always been broken and the Ivy league merely proves it.

In a true meritocracy, people are supposed to advance through the ranks of society on the basis of “demonstrated abilities” — according to Merriam-Webster, of course. But the idea that every child, or every person, in America is capable of demonstrating the full extent of their abilities or merit is frankly only conceivable for those who themselves possess at least a moderate degree of privilege.

The inability of different social groups to adequately represent their “merit” is evidenced in Princeton’s own admissions statistics. As my colleague Raf Basas recently pointed out, Princeton is nowhere near as socioeconomically diverse as many seem to believe: students from the bottom 60 percent of the income distribution make up just 31 percent of students. Brooks furthers this point, stating that “students from families in the top 1 percent of earners were 77 times more likely to attend an Ivy League–level school than students from families making $30,000 a year or less.”

While Princeton’s current racial demographics are more representative, they ultimately still miss the mark compared to the racial diversity of Generation Z. At present, 9 percent of Princeton’s Class of 2028 is Black as compared to 14 percent of Gen Z. Additionally, just 9 percent of Princeton students are Hispanic or Latino, compared to 25 percent of Gen Z.

Should we interpret these statistics to mean that high-income White and Asian students are vastly more “meritful” than students of color or students from families in the bottom 60 percent of earners? I don’t think so.

Rather, these numbers indicate that the metrics on which we measure students — SAT scores, GPA, extracurricular activities — inherently disadvantage those from lower socioeconomic status. But then, how are we meant to evaluate students in a way that controls for limiting societal factors? In affirmative action, we at least had an idea of an answer.

In his article, Brooks puts forward alternative metrics by which we should measure “merit,” with the hopes that they would create a more egalitarian admissions process to our country’s elite institutions. He argues that aspects like curiosity, agility, and social intelligence should be weighted equally with IQ in these processes.

Personally, I think that the use of alternative metrics is a fine idea, and could even help eliminate some of the elite-funneling into these institutions. However, no metric will ever be perfect. Contrary to Brooks’ argument, the inequality that we see in elite-college admissions is not manufactured by present-day admissions processes.

Over the past decades, we have seen broad efforts to manufacture equality in admissions via affirmative action. These efforts not only failed to make university student bodies that were representative of the larger population, but were susceptible to attacks from conservatives.

The reality is that no amount of policy reform can create equal admissions in an unequal society. America is the land of inequality disguised as opportunity, and though elite institutions have played a role in that historically, they are a symptom, not a cause.

Meritocracy cannot coexist with extreme systemic inequality, and we need to stop pretending that it can. Instead of hypothesizing around how to create marginal improvements to elite college admissions we should focus on tackling the extreme inequalities that persist in American society. If we argue that elite schools are run by meritocracy, and then they admit students from the top 1 percent at much higher rates than any other group, wouldn’t the logical conclusion be that those students are inherently superior?

The myth of meritocracy not only distracts from the realities of American inequality; it exacerbates them. In a society that systematically oppresses certain groups, you cannot ignore the extreme disparities of past experiences, and evaluate every citizen on a set of criteria fit for only one group, without devaluing those with fewer opportunities.

When you disregard existing inequalities under the guise of egalitarianism, you imply that those who are less fortunate are inherently inferior. The way that we talk about this system not only impacts the real lives of real Americans, but it can also affect how we perceive our peers. As this implication becomes increasingly ingrained into our national psyche, it becomes impossible for some to conceptualize that certain people, those who have always come last in the race designed for them to lose, could ever come out on top.

Ava Johnson is a sophomore opinion columnist and prospective Politics major from Washington, D.C. Her column, “The New Nassau,” runs every three weeks on Mondays. You can read all her columns here. She can be reached by email at aj9432[at]princeton.edu.