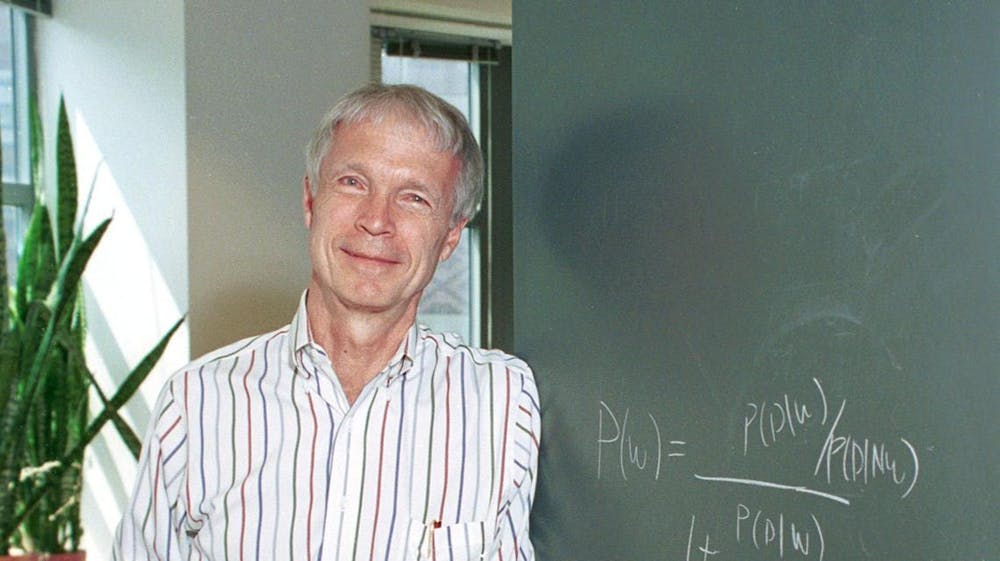

Professor Emeritus John Hopfield was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics on Oct. 8. He won the prize jointly with Geoffrey Hinton, known as the godfather of artificial intelligence (AI), for their work in “foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

The Daily Princetonian, with The Cornell Sun and The Swarthmore Phoenix due to time constraints, interviewed Hopfield to discuss his career in physics, influences, and life as a Nobel laureate.

Hopfield expressed that his “upbringing was different” from many of his peers. He explained that his parents both had advanced physics degrees and “knew about how the devices of the world functioned.”

Hopfield’s father, John Joseph Hopfield Sr., had a PhD in physics from UC Berkeley, while his mother, Helen Hopfield, earned her M.A. in physics from Mount Holyoke College in 1924.

Hopfield himself obtained his undergraduate degree from Swarthmore College in 1954, and his PhD from Cornell University in 1958.

At Swarthmore, Hopfield followed a liberal arts education to major in physics under advisor William Elmore, then chair of the Swarthmore Physics Department. Hopfield recounted first meeting Elmore, after applying to Swarthmore planning on majoring in either chemistry or physics. “[Elmore] got out his pen, drew a black line through chemistry, and said, ‘I don’t think we need to consider chemistry.’ He was right, but that was a decision point.”

Hopfield touched on how his liberal arts education led him to learn about “very broad things which were not part of the curriculum.” He attended regular colloquiums — known as “collections” at Swarthmore — hosted by the college. He recalled hearing a lecture about the American Civil Liberties Union, explaining that he always went to the collections, “and found it just engrossing.” He added, “it was a big part of my education, of my liberal education.”

Hopfield spoke fondly of his days at Cornell, and specifically his doctoral thesis advisor, Dr. Albert Overhauser. He described Overhauser as someone who had been somewhat ostracized by the scientific community for his initially-doubted work on spin resonance in lithium metal, but was a “marvelous” thesis advisor and a “great listener.”

“He didn’t tell me what to do,” Hopfield remembered. “He gave me a couple things that were puzzles which he didn’t know how to solve. I took over those puzzles and solved [them]. And that was my thesis. But he never told me what to do. He came in and listened.”

Hopfield said that he tried to emulate Overhauser’s advising methods with his own advisees.

“I’ve begun to treat my best students with the same passion he had, encouraging thinking for yourself about a system. And don’t be afraid if what you’re thinking does not look popular,” he said.

Hopfield was hired at Princeton in 1964 in the Department of Physics, and taught until 1980. He then spent a stint teaching at CalTech before rejoining Princeton in 1997, where he is now the Howard A. Prior Professor of Molecular Biology Emeritus.

When he first joined Princeton, he worked in condensed matter physics, until he “ran out of problems to work on.” That’s when he started looking toward biological questions.

“That’s not really the purpose for which Princeton had hired me,” Hopfield said. “They had a biology department. They hadn’t hired me to be in it. And so at that point, I did wander … where I was jointly between chemistry and biology, and free to do different things, free intellectually. I was no longer in a niche which Princeton had put me in and I had previously agreed to.”

In his defense of his intellectual move to biology, Hopfield explained “there’s a physics to how life works.” He noted that biological physics is too broad, so he couldn’t research all of it. However, he did look into “one of the particular questions, which always lies there”: how do humans think?

Hopfield explained that physics offered him a different approach to this question, with ways that are “related mathematically to some entirely different phenomena which are studied in physics.”

When asked about his work that contributed to his Nobel Prize win, Hopfield explained that machine learning is “a field which didn’t exist 20 years ago.” Machine learning is a branch of computer science and AI which allows computers to adapt and learn new procedures without assistance.

Hopfield suggested that machine learning is “not broad enough to take seriously as an undergraduate major.” He advised that students should seek foundational knowledge in a field such as computer science or neuroscience. “You will always, to some extent, remain with the label of your undergraduate major. Be sure to find a fairly broad label,” he said.

Post-Nobel Prize has been a new exciting chapter for Hopfield. “I had never seen 100 emails before in my life,” he said. He expressed that his life was changed by the announcement; “the whole next two months that I had previously planned did not exist [anymore].”

Hopfield concluded, “It was wonderful. Still is.”

Mahya Fazel-Zarandi is a senior News contributor for the ‘Prince.’

Assistant News Editor Victoria Davies and Senior News Editor Charlie Roth contributed reporting.