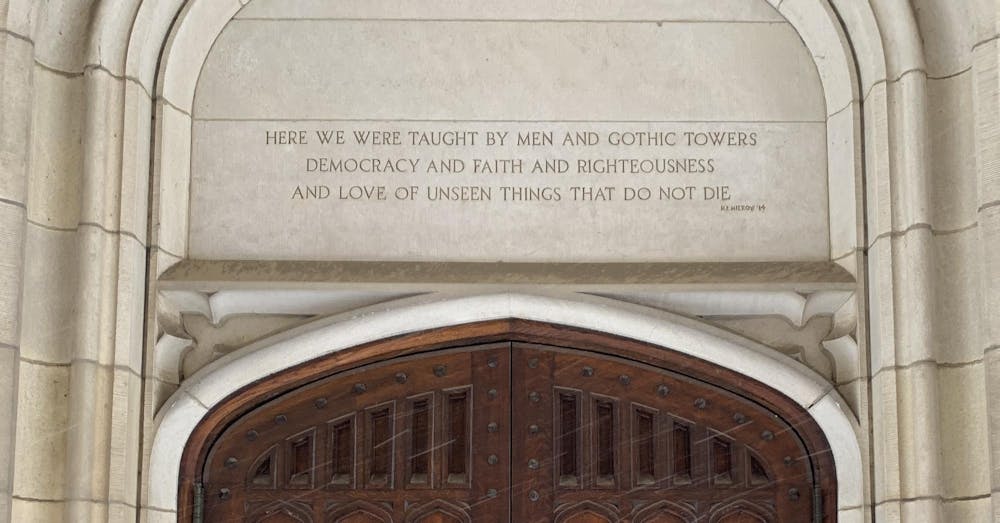

“Here we were taught by men and gothic towers / Democracy and faith and righteousness / And love of unseen things that do not die” declares an inscription under an arch bridging the two sides of McCosh Hall. Here at Princeton, even the walls roar that attaining democratic virtues is a primary pursuit of students.

It might be confusing, then, to find that this democratic education does not include actually participating in one: To undergo the apprenticeship for good citizenship, the University demands compliance with its program. This exchange is not something that students should attempt to reject by calling for increased participation in Princeton’s governance. An institution committed to investigating and discovering the truth cannot leave such important concerns to the whims of the yet-to-be-educated majority.

Throughout the Ivy League, students are increasingly uncomfortable with the idea that when they enter their universities, they give something up — other than the thousands of dollars that grant them access in the first place. Pushes to introduce democracy into university governing schemes have recently proliferated. Yalies voted in favor of “democratizing” the board of trustees in 2023, expressing via referendum that they believed students, professors, and staff should be able to vote on candidates for the Yale Corporation’s board of trustees. 4,000 Columbia University students withheld their tuition in 2021 in hopes of achieving a “democratized University” which would “respect the democratic votes of the student body.”

At Princeton, democratization efforts focus on giving students more control over the University’s funding structures. One of the four principal demands of Sunrise Princeton, an organization engaging with “climate justice organizing” and focused on redirecting the University endowment, is to “democratize governance” to give students power. Members of Princeton Israeli Apartheid Divest recently criticized the Council of the Princeton University Committee (CPUC) Resources Committee for failing to appropriately solicit community input on the proposal to divest from a slew of investments in and research partnerships with groups associated with Israel.

Theorizing the University as a democracy which should base its decisions on the opinion of students, however, is a fundamentally misguided approach to higher education. To demand that university life change according to our desires is to prioritize our current notions of what is good, necessary, and important in life, rather than actually commit to the life of a student, which involves acknowledging one’s own unenlightenment in those crucial ideas. An education — which is intertwined with the apparatus which enables it — is not a commodity, and students are not consumers with purchasing power.

After all, what does it mean to be a student? Is it to know exactly what you need, and how you should go about obtaining it? Or is it to humble yourself, accept your lack of knowledge, and proceed to listen and learn? The latter is what Princeton requests from its students, and rightly so.

In the midst of gaining an education, students are bound to reason some things correctly. Changes they call for are not necessarily wrong; student advocacy can often promote useful ways to develop Princeton and its mission. Yet the reason these changes are good is not because a majority (or loud minority) of students want them. It’s not possible to judge virtue through a vote, but it’s imperative that Princeton considers that before making reforms. This is why the Board of Trustees and particular administrators are entrusted with the power of change, because they also have the task of judging on these bases. They don’t always get it right, but at least that’s their task, which is not what is entrusted to the crowd.

Becoming an undergraduate entails signing a metaphysical contract with an educational institution. “I don’t know things,” we say. “Teach me.” And the University does (or should).

This is not a nefarious contract, but an exchange central to the educational process that institutions like Princeton strive to maintain as sacrosanct. In this manner, the University functions more like a monarchy than a democracy: I often refer to Old Nassau as the Kingdom of Princeton. President Christopher Eisgruber ’83, our leader, plots the path of this community. He supervises the University’s interests, and though he shares power with the Board of Trustees, he is also a member of this group and is in fact absolute. The University Bylaws do not contain any provision for his removal.

In this position, he has many subjects: the scholars, the staff, and the students. He also has peers (the donors) and foreign advisors (the alumni). While undergraduates love to think that we form the core constituency of Princeton, to which our leaders are interested in responding, we do not. Educating us is a core mission of the institution, yes. But meeting our desires is far from its goal. King — sorry, President — Eisgruber recently explained why he does not grant us a major voice in institutional affairs.

“The fact that you’re here today, and some building’s going to get finished after you graduate, doesn’t mean that your views about that should be the deciding views about what happens,” he said in conversation with the Daily Princetonian last year.

It is precisely this situation that students clamoring to be listened to often forget. The University does not exist to meet our desires: we come to the University to receive what it exists to offer. Becoming educated in order to lead an examined life can also constitute preparation to be good members of democratic societies. Thus, the fact that a University does not use democratic means to grant this education may seem counterintuitive: how can it be that one must first submit to being a voiceless subject in order to become a citizen?

This is no easy paradox to understand, but that does not mean it is a problematic one that needs to be resolved. Indeed, willingly subjecting oneself to being a Princeton student gives undergraduates the freedom to explore precisely these sorts of questions. True learning, in the University setting, cannot take place on a plane where all community members are equal. It is our role as students to follow the instruction of our instructors.

A democracy is founded on political equality, but a University exists to allow an unequal power structure in which we, the students, commit to gaining knowledge through being educated by our more learned superiors. We recognize that students are less able to interact with knowledge because they do not yet possess a college degree. While in pursuit of their diploma, students should certainly engage in rigorous discourse within the framework their educational guides provide. But they do not belong in the boardroom. To propose that their opinions should have any binding effect, particularly via a democratic process, is to reject the idea that students are, in fact, students, people who have not attained the same knowledge as graduates, and are thus less capable of responding to complex problems. It is to reject the very value of a college education.

An undergraduate recently criticized the University’s decision to keep the John Witherspoon statue on campus, noting that it was the result of “universities having an autocratic structure, not [being] democratically controlled by its community.” This is true, though I think it’s an example of the University functioning exactly as it should. How to govern an institution older than the nation itself cannot and should not be determined by students, who have only belonged to Princeton for a fraction of its lifespan.

Abigail Rabieh is a senior in the history department from Cambridge, Mass. She is the Public Editor at the ‘Prince,’ and can be reached via email at arabieh[at]princeton.edu or on X at @AbigailRabieh.