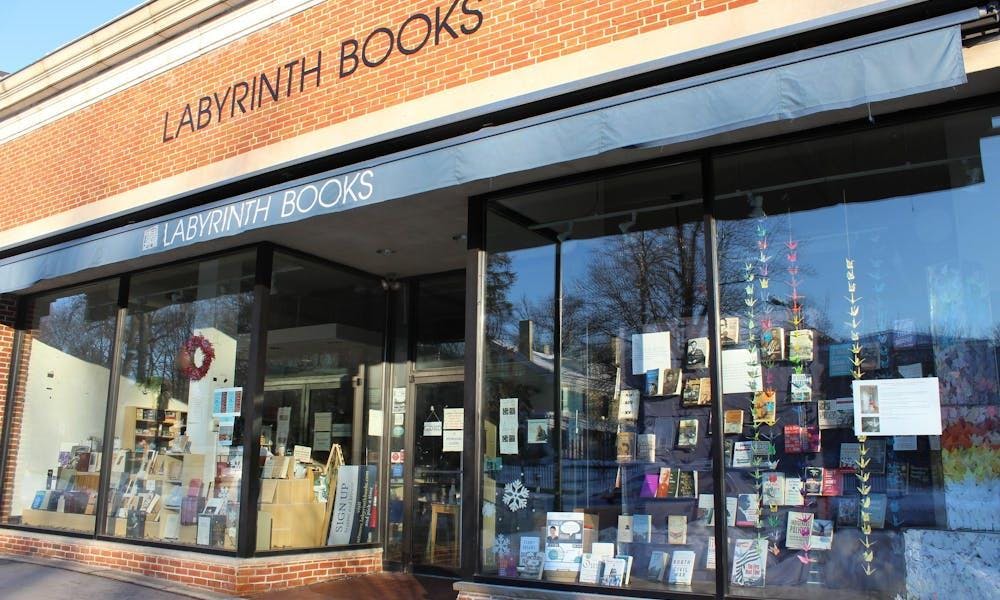

The beginning of a new semester comes with a routine we’ve learned by rote. Greet the old friends, vow to “get a meal sometime!” — you probably won’t, and that’s probably fine. Purchase binders, folders, and notebooks if you’re the write-by-hand sort. Then, go to Labyrinth with a few sturdy amici in tow and prepare to haul your dog-eared copies of Plato and Joyce home in anticipation of classes beginning. It was a good life, looking back.

With the advent of “eCampus Online Bookstore,” this solemn rite must now be done alone, hunched over a laptop screen. There is some associated convenience: no sore shoulders, fewer trips, and no dreaded “out of stock” messages. Caitlin Donahue, Course Materials Manager at McGraw, says the switch to eCampus also allows the harried (but universally sweet) Labyrinth employees to focus on their roles running a local bookstore, instead of helping hunt down a copy of “Virtue Ethics for Consultants.”

However, for student book buyers, eCampus is slower and more expensive than Labyrinth was. Ultimately, the switch replaces an economic and spiritual pillar of the community with yet another e-commerce conglomerate.

First, take “slow”: some books took over a week to arrive with the new service and weren’t in students’ hands until well after the start of fall courses. The advantage of buying at Labyrinth was efficiency: you walked out of the store with most of your books, and received those that required a separate order within two days. Princeton’s twelve week semester means that coursework comes at you fast, and a lost week of reading can mean falling behind when a course has barely begun.

Choosing from a selection of books in-person also allowed for far more choice, especially for students who need to buy used books for financial reasons. “The Peaceable Kingdom” by Stanley Hauerwas costs $29.24 to buy on eCampus, but only $13.98 to buy from Labyrinth — and eCampus takes a full three to five more business days to receive after ordering.

And the inability to decide what level of disrepair is acceptable is frustrating. eCampus only allows you to choose between new, used, rentals, and ebooks. The stochastic assignment of copies by a faceless algorithm removes the tangible benefits of buying books in the physical world.

However, this argument about price and convenience cannot capture why I care so deeply about buying course books at Labyrinth. Sure, my English-major opinions on books are many and ardent. Still, we all should fear a post-Labyrinth universe.

Selling marked-up course books most definitely turns a profit. When Labyrinth did it, we could be relatively certain that our money was going toward a local bookstore in a time when these invaluable businesses are dropping like flies. From 1998–2020, over 50 percent of America’s independent bookstores closed down for good. The total amount I paid for my books each semester has remained roughly the same from freshman year to now, but my money now disappears into the online aether with the click of a button.

Who are we paying, and why haven’t the prices dropped with the customer-service element removed? eCampus spent a decade as one of Amazon’s partners before breaking off to go into the business of textbook rentals and sales after Amazon broadened its scope, leaving a sizable gap in online course book sales. At least one new book a student ordered from eCampus arrived in Amazon packaging, which should set off alarm bells. Has Princeton redirected our book money from a local business to one of the wealthiest companies on the planet – and are we paying even more for the privilege?

Meanwhile, Labyrinth is a veritable Princeton institution and a symbol both of this particular community and the necessary, waning brotherhood of independent booksellers across the country. Without the revenue from thousands of students buying multiple books at a time, will Labyrinth’s position in the marketplace become untenable?

The pestilence of the modern world is how quickly it alienates us from the human aspect of everything. A book has passed through dozens of caring hands before it reached yours. That chain takes corporeal form in a place like Labyrinth, where the workers give directions and effusive recommendations while you browse. They care about the wares they peddle — and so did everyone else who made possible the precious hundreds of bound pages you throw in your bag, on desks, and atop the odd creepy-crawly in need of squishing. A book is the triumph of years and lives; it reminds us that the pursuit of higher knowledge is a fundamentally human endeavor. You have to try hard to be disaffected and lethargic when you’re holding a sweet-smelling, fresh tome of your very own. Door swings open; Jersey sunlight floods in behind the customers. Muted swish of paper on paper. Doorbell jingles: you are here, you are here, you are here.

Anna Ferris is a junior in the English department. She can be reached at annaferris[at]princeton.edu