After the filming of Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” on campus in 2022, “the bomb” returns to Princeton — this time as a special exhibition for the 50th Anniversary of Princeton’s Program on Science and Global Security (SGS).

“It was so overwhelming that I had to remind myself to breathe,” Alexandra Bodrova said, a Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Ph.D. student in the program, “Finally, after what felt like an eternity, a strong sense of hope and a desperate urge to act emerged. Act here and now.”

In the Bernstein Gallery of Robertson Hall, “the bomb” exhibition prompts viewers to grapple with the existence and threat of nuclear weapons. The exhibit, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the SGS at Princeton, opened on Sept. 19 and will remain on display until Oct. 25 before going to the next stop on its nationwide tour.

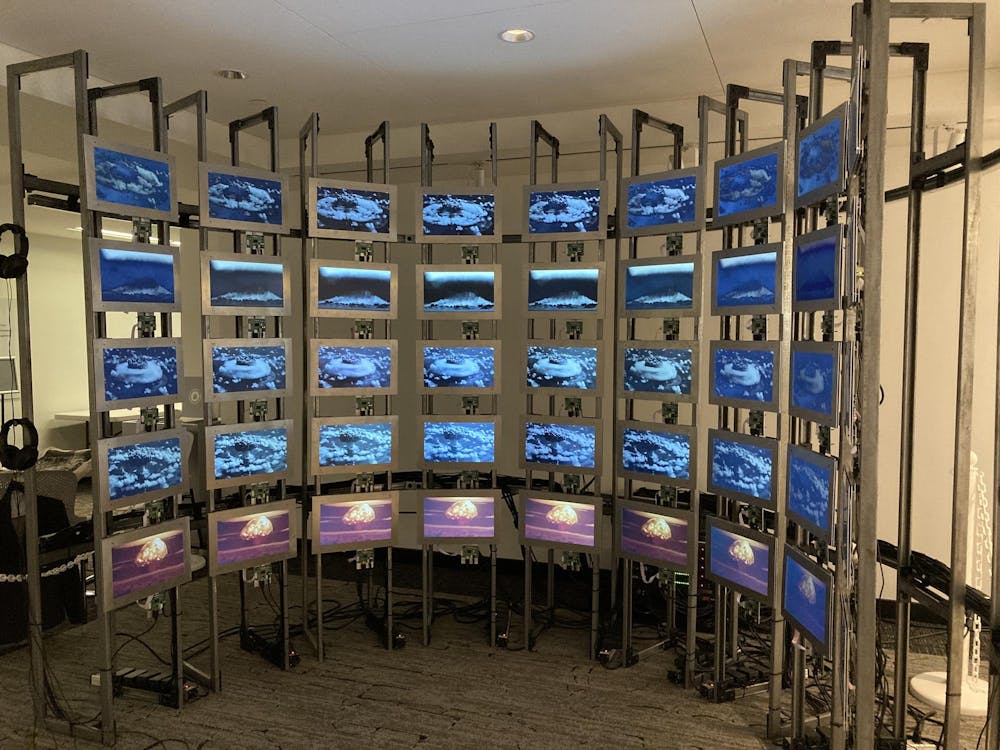

“The bomb” was designed by filmmaker Smriti Keshari and journalist Eric Schlosser ’81. The installation, a semi-circular arrangement of 45 screens, resembles a nuclear weapon command-and-control center. Each screen displays video footage related to global nuclear affairs, ranging from the first nuclear test to arrays of nuclear weapons ready for launch on land, underground, and at sea.

The exhibit aims to spotlight the technological fragility of nuclear systems, which are often seen as symbols of power and national strength. Rather than presenting viewers with a definite answer about the ethics of nuclear weapons, the artists said they hope that “the bomb” will prompt viewers to ask more questions.

“The bomb” was inspired by Schlosser’s book “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety,” which explores the complexities and dangers of nuclear weapons.

The artist, Keshari, said the book left a profound impact as it helped her to understand the nuclear reality of today’s world. “It takes you through all of the emotions,” she said.

To prompt reflection by the viewer, Keshari deliberately omitted narration and text from the wall of screens simulating a nuclear command center.

“All of those kinds of emotions were what I wanted to evoke, and what I wanted an audience to be able to feel,” she said. “And not [to] tell them [whether] this is good or bad, but really take them through this emotional journey at the very heart of nuclear weapons and leave them wanting to ask more questions.”

Schlosser said the exhibition also emphasized on the vulnerability of technological systems, with visible wires and screens and stories about real accidents. For example, in 1980 when a security officer at an Arkansas missile silo used the wrong tool to repair a fuse, he caused a short circuit, leading to the nuclear missile’s detonation inside the silo.

“It’s that kind of crazy, haywire system,” Schlosser said. “It’s one thing if you’re plugging in your home entertainment system, and you set off your smoke alarm, but when there’s a nuclear weapon involved, the consequences are just catastrophic.”

The exhibition highlights the delicate, volatile nature of controlling something as powerful as a nuclear bomb.

“At the heart of my book, and at the heart of the film that Smriti and I made, is the issue of how we control the complex technological systems that we make,” Schlosser said. “We’re much better at creating them than we are at controlling them.”

Controlling nuclear weapons has been a focus of researchers of the SGS, which was established 50 years ago.

“I think what distinguishes our group is that we are mostly technically trained folks, and we try to use these skills to inform and design policy,” said Alex Glaser, an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and SPIA.

To celebrate its anniversary, the program looked to share its work with a broader audience by taking an interdisciplinary approach, displaying “the bomb” and presenting the Bruce Blair Memorial Lecture, featuring a panel on nuclear disarmament.

The panel was hosted by SGS Co-Director Zia Mian, with special guests including the exhibition artists, Keshari and Schlosser, and Annie Jacobsen ’89, journalist and the author of “Nuclear War: A Scenario.”

The panelists described the historical and contemporary risks of nuclear weapons, the challenges of highly centralized command-and-control centers, and the accidents that are derived from technology, military requirements, and war plans.

In his speech, Schlosser noted that nuclear systems, though embodiments of power and science, are as intricate as they are complex. Most nuclear incidents in history result from unforeseen accidents or even measures intended for safety, he pointed out.

“When you look back at these [systems], you see incredible technological skill of our weapons designers, you see great administrative skill of the people who created the management systems, great heroism, and a good deal of luck,” Schlosser said. “Luck is something that you don’t want to rely on when you’re talking about potential catastrophes.”

Jacobsen’s book, “Nuclear War: A Scenario,” explores a hypothetical scenario in which the international nuclear state of affairs indeed goes wrong. Her reporting is based on many interviews with people at the center of nuclear decision-making, from Dr. Richard L. Garwin, author of the first hydrogen bomb design, to government officials like U.S. Secretary of Defense and Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Leon E. Panetta. Some of these figures had not given interviews previously.

“[I used to believe] that there’s kind of a nuclear priesthood — people [who] know more than me and don’t want to share that information,” Jacobsen said. “One of the most hopeful things about my reporting was that I found the exact opposite to be true. You can see that in the list of interviews, people who are knowledgeable and are willing to share this knowledge.”

Like Jacobsen’s reporting, Keshari’s work on “the bomb” also aims at engaging the public in the nuclear conversation using art and film as her avenue.

“Again and again and again, it’s culture that has been at the forefront,” Keshari said. “It’s the arts, it’s writers, it’s poets, it’s musicians, it’s film, and I think that’s such a power we have. That was really at the heart of the making of “the bomb” and how you could take people through this emotional, visceral, visual relationship to understanding nuclear weapons.”

Students from various backgrounds and years of study have visited the exhibit in the Bernstein Gallery. In particular, students from SPI/MAE 353: Science and Global Security: From Nuclear Weapons to Cyberwarfare and Artificial Intelligence, took a class trip to see “the bomb.”

Hajra Hamid ’25, a SPIA major, recalled “the bomb” as an eye-opening experience that represented a “very real possibility of mass destruction.”

“The way the screens surround you creates an immersive experience that really drives home the catastrophic power of nuclear weapons,” Hamid wrote in an email to the ‘Prince.’ “Even though you’re not physically present in a nuclear disaster, the installation gives you a haunting sense of how omnipresent the nuclear threat truly is.

For other students, the exhibit represented a bridge between the conceptual theories they learn in class and the realities of nuclear warfare. Sujay Swain ’25, an electrical and computer engineering major also in SPI 353, recognized the impact of the exhibit’s technical elements.

“As an engineer interested in policy, it really pushed me to think more critically about these issues,” Swain wrote. “Understanding how close we are to a catastrophic nuclear disaster made the exhibit feel like a warning rather than a piece of history. That was both scary and inspiring.”

Bodrova, a MAE Ph.D. student in the program of Science and Global Security, described feeling “a whirlwind of emotions” from deep fear to profound grief.

“From that moment, my priority has become reclaiming control and turning hope into action,” Bodrova said. “I believe that together, we can ensure the devastation I witnessed on those screens remains a lesson from history, never to repeat in our present or future.”

Leo Yu ’26, a computer science major, worked with a few other students to design a survey about how the exhibit impacted students’ perspectives.

“Viewing this exhibit and my work creating the survey prompted me to re-examine how invisible nuclear weapons are — almost as invisible as they are destructive,” Yu said. “The multimedia format definitely helps bring at least part of the reality of nuclear weapons into the gallery space.

After Princeton, “the bomb” exhibit will be presented at universities across the country, though future locations have yet to be announced. According to Keshari, “the bomb” has been featured at many film festivals and art festivals, including the Glastonbury Festival and the Nobel Prize ceremony.

“When I asked a lot of people, early in my days of nuclear weapons, why they got involved in the subject matter, it usually went back to a photograph or a film that they saw when they were a teenager or in college that kind of was that first seed,” Keshari said.

“We’ll never be able to measure [the impact of our work],” she continued, “but I really hope “the bomb” is that seed [for the audience].”

Chloe Lau is a staff Features writer and contributing Prospect and News writer for the ‘Prince.’

Coco Gong is a staff Features writer for the ‘Prince.’