I would characterize my first year at Princeton as a melting pot, in which people of various backgrounds and ideas swirled together in our beloved Orange Bubble. The friends I’ve made come from different backgrounds, with many of them being second-generation Asian Americans. Some of them would converse with each other in Mandarin and compare regional dialects. Others would share funny Vietnamese quips that are better kept amongst ourselves. My boyfriend only spoke to his mother in Korean over the phone.

I’ll admit it, I’m jealous.

Not of them, per se, but of their bilingual abilities. I’ve grown up surrounded by an enormous first-generation family. I recall my aunties and uncles gossiping in Tagalog while their children played Nintendo Wii in the next room. Growing up, we always responded to them in English — now, some of us have lost the ability to understand entirely.

I consider myself to be the most fluent in Tagalog among my cousins, but still, my Tagalog is broken. While I can understand the language, my mind stalls and jumbles the puzzle pieces of vocabulary and grammar required to hold a fluid conversation. This is a prime example of receptive bilingualism: a native-like comprehension of a language but no active command over it in speech.

I’ve been in a one-sided battle with my culture my whole life, even as a proud Filipino. Speaking Spanish since middle school and learning Korean at Princeton, I can’t help but feel like I’m betraying my mother tongue by putting other languages first.

A few months ago, my twin sister, a fellow Princeton student, discovered Princeton’s new Less-Commonly Taught Language Summer Initiative (LCTL), a funding opportunity that provides resources for students to independently learn a language not taught at Princeton. After some applications and paperwork, I was connected to a tutor in the Philippines, taking 1.5-hour lessons twice a week.

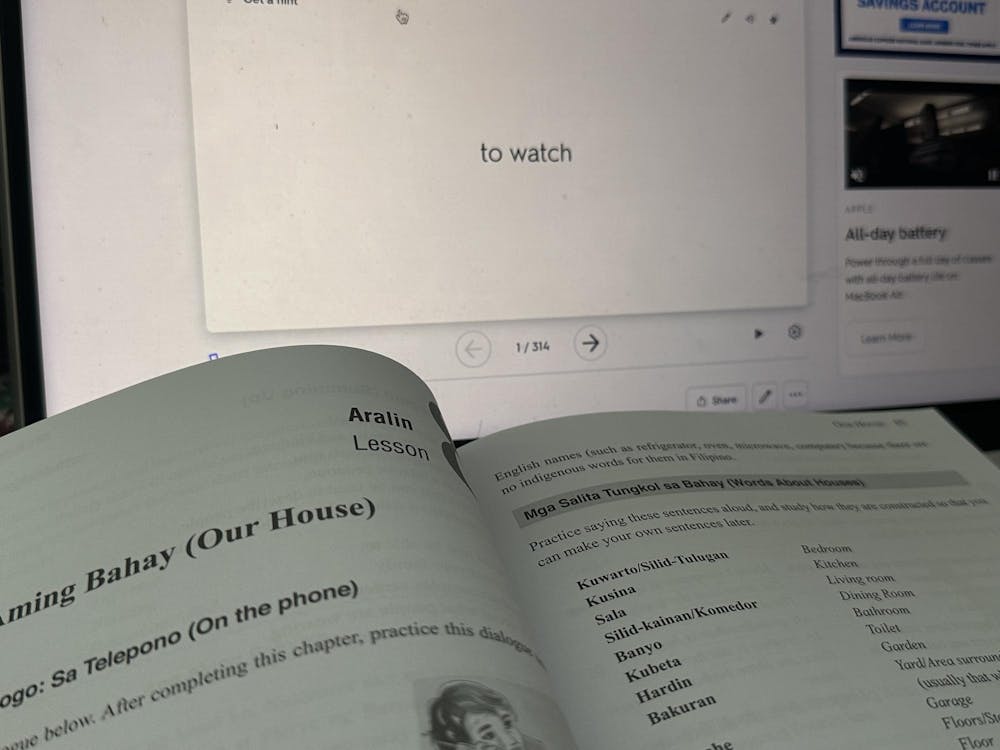

My tutor quickly remarked that I was already proficient in the language, which felt like a double-edged sword. We flew through the first few chapters of my textbook, which were mainly vocabulary and greetings. However, when it came to freestyle conversations, I was slow to form sentences. More importantly, when presented with sentence structure, I’d struggle to explain why the sentence is the way it was. I needed one thing: to practice.

Outside of lessons, I made a Quizlet for verb tenses — but with a twist. In Tagalog, the conjugation of the verb is also contingent on the intention of the verb. Who is doing the action? What is the verb acting upon? Is the verb doing something for someone’s benefit? For example, the word gawa meaning, to do or to make, can be gumagawa if focused on the maker but ginagawa if focused on the thing that is being done. But, it can also be ginagawan if you’re making something for someone. As a result, my Quizlet is now 400 words and counting. I have found that memorizing each root verb — along with its various conjugation cases — has been more useful in conversation, as it makes my intentions clearer to the listener.

An important part of learning a language is immersion. While I’ve understood Tagalog my whole life, I had to force myself to speak in Tagalog back to my family members. Being a talkative person, it was difficult to pause and consciously string together words. However, I’ve noticed myself responding with a smoother, more natural tone.

I’ve also been incorporating talking in Tagalog at work, where almost everyone speaks the language. I talk to the staff in short sentences just for practice. But more memorably, a patient asked me, “Pilipino ka?” or “Are you Filipino?” I was confident to answer more than I was before, even though it was just small talk. Many of the elders have begun speaking English in my Filipino-American neighborhood, so sharing our language brings us both a sense of belonging and community.

As the summer draws to a close, I’m reflecting on a question asked on the LCTL application: how will you use the language you will be studying when you return to Princeton? As an active member of the campus organization Princeton Filipino Community, I understand the importance of promoting and celebrating Filipino culture in all forms. Whether that be continuing my studies in the language to study abroad in the Philippines or to teach my peers some phrases in Tagalog, being Filipino isn’t all about knowing the language. It’s about putting community first in your words and actions.

Brianna Melanie Suliguin is a staff writer for The Prospect. She is a part of the Great Class of 2027 and is from Toms River, N.J. She can be contacted at bs7122@princeton.edu.