The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone. For information on how to submit a piece to the Opinion section, click here.

When the cornerstone of East Pyne Hall was laid in 1897, Princeton alumni were resolutely furious. They dubbed it the “Crime of ‘97,” rebuking the discordant look of the Victorian Gothic building and mourning the demolition of the old chapel and East College. They felt that the new style of East Pyne could not compare to the erstwhile aesthetic of the university. Sound familiar?

The “Crime of ‘97” overshadowing Nassau Hall, ca. 1920s.

Courtesy of Princeton University Archives, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Today, of course, East Pyne is upheld as a scion of Princeton architecture and criticism has turned elsewhere. In 1999, Catesby Leigh ’79 lamented Frist and Woolworth as “architecture whose spiritual horizons have narrowed to the point of utter inconsequentiality.” While these buildings have gained acceptance, the deconstructivist Lewis Library was recently denounced as a “Minecraft glitch,” and many now bemoan the austere aesthetics of Princeton’s contemporary construction.

But this reproach ignores how architectural ideals are determined and who a style is meant to serve. Princeton’s newest buildings are not intended to reinvigorate the past. Rather, the new style disengages from traditional footprints and facades to draft a novel visual language for Princeton.

Many of the cherished historic buildings on our campus obey a decorative agenda, holding that the outward appearance of a structure can be divorced from, and supersede, our residential uses for it. Conversely, the new style posits that a structure’s form must be thoroughly attuned to the human interactions it will facilitate. Princeton’s contemporary, post-decorative pursuit denies the separation of appearance from function, abandoning the project of visual hegemony and taking assertive aesthetic risks.

Architect’s rendering of Hobson College facing east towards Guyot.

Courtesy of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism studio (PAU)

The nostalgic architecture most frequently heralded in critiques is that of Ralph Adams Cram, the prodigious early 20th-century architect behind much of Princeton’s upperclass housing. Cram sought to evoke the elite educational atmospheres of Oxford and Cambridge in his work, assuming homogeneity in gender, ability, and lived experience among its inhabitants. This is readily observable: his structures rely on single-gender occupancy for facilities, exhibit low accessibility, and, built before the relatively recent notion of ‘campus culture,’ contain a dearth of communal spaces.

Yeh College (left) and New College West (right) upon completion in 2022.

Courtesy of Denise Applewhite / Office of Communications

As opposed to Cram’s more imitative approach, the architectural firm TenBerke’s design for Yeh College and New College West started from scratch to discern how a community could thrive at Princeton. Their approach was guided by ambitious ideals including the permeation of the outdoors indoors, degendered privacy, total accessibility, the primacy of community, and sustainable climate control. The colleges feature spaces for performing, dining, art-making, and socializing unseen in Cram's older sites. Thus, they don’t “look like” anything else on campus — that’s the point. Our housing need not be imitative, it can boldly put forward a new thesis about the nature of communities.

Art Museum progress by Winter 2023, facing northeast

Courtesy of Robert Mohan

To enjoy purpose-built architecture, we cannot construct nostalgically. Whitman College lies stuck in an architectural ‘uncanny valley’ as an unsuccessful hybrid of the contemporary and traditional. It attempts to replicate Cram’s masonry charm without access to its traditional artisans or reference points. The result is disorienting: Whitman’s Community Hall is nearly devoid of decoration beyond the first eleven feet of height, a far cry from the intricate beams, colorful stained glass, and wooden grotesques of traditional neo-Gothic halls. Although it has some exceptionally well-designed vignettes, such as its drawbridge entrance and central tower, the complex as a whole does not form a confident aesthetic assertion.

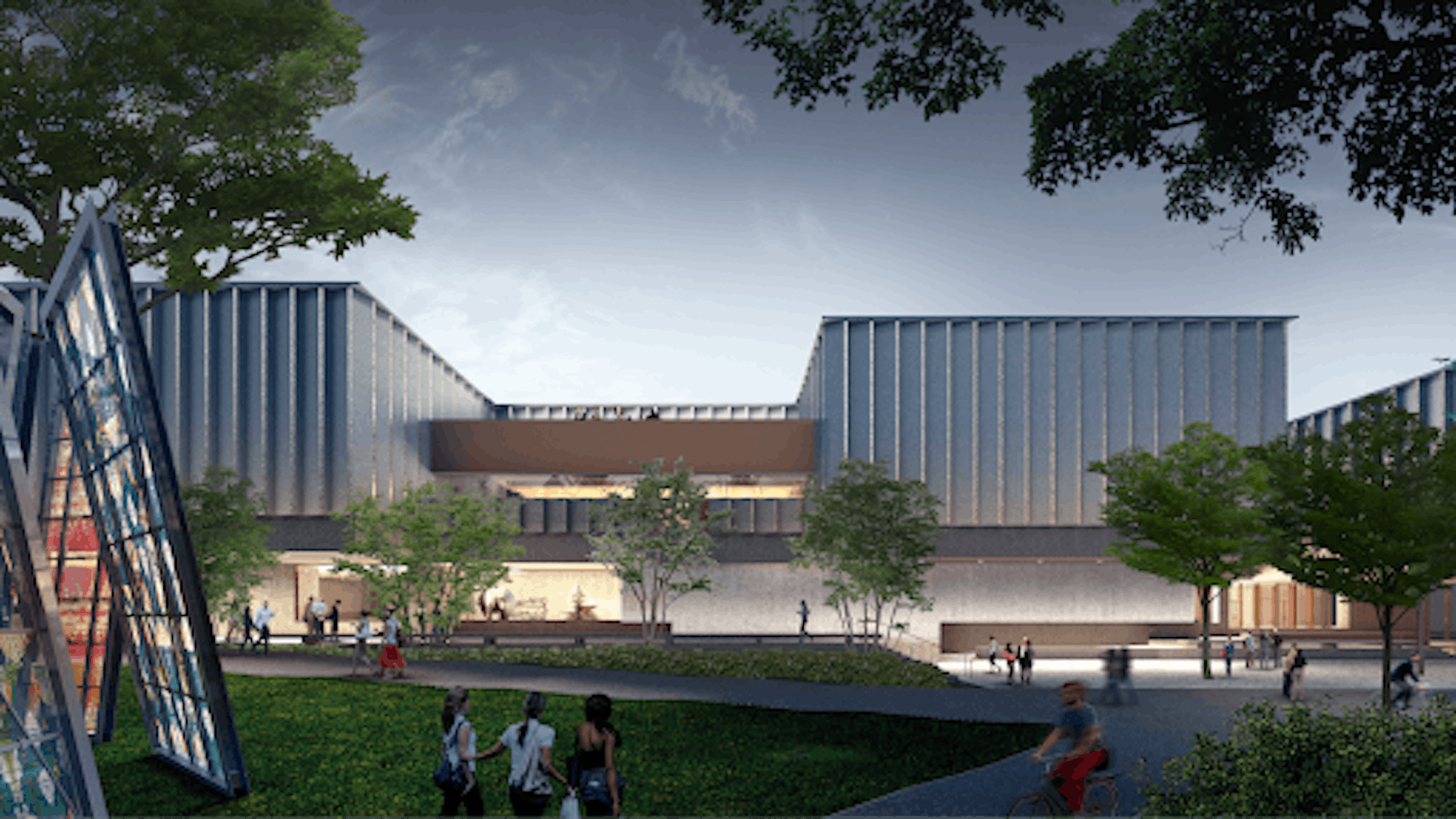

Architect’s rendering for the new Princeton University Art Museum, facing east.

Courtesy of Adjaye Associates

On the other hand, the contemporary projects are unapologetically of our time: they ditch the mimicry of revival and the irony of postmodernism, preferring an aesthetic of sincerity. The monolithic buildings reflect the University’s collectivist ethos, suggesting stalwart communities and grounded institutions. The peripheral arms of Yeh wind across greenspaces to conjoin at strange angles, the edges crisp and the brickwork clean. Forget Cram’s isolated entranceways and tight passes — this is architecture intentionally scaled up, where buildings become expansive hubs for connectivity. Beyond their aesthetic merit, these works also vigorously promote sustainability, the profusion of mass timber across the new projects serving as a fine case study in both material sincerity and carbon-conscious engineering.

Architect’s rendering of Hobson College as seen from Whitman Lawn.

Courtesy of PAU

Critics of this contemporary aesthetic often construe the project as a struggle against tradition. Noted architect Mark Alan Hewitt argued that in the construction of the new residential college bearing her name, Mellody Hobson ’91 should press for architecture that “represents continuity rather than obtrusive change.” Julianna Lee ’25 shared a similar opinion, asserting that continuity in style allows Princeton to “remain Princeton.” Unlike Hewitt and Lee, I believe that the great, ineffable continuity of Princeton lies in its lineage of students. This communal continuity beautifully transcends the current built landscape and instead seeks to manifest in a range of new physical spaces.

Princeton is decisively ushering in new institutional values, and new construction is styling the campus to reflect them. When Hobson College’s concept plan was revealed in February 2022, Princeton Municipal Planner Michael LaPlace pushed back, saying that “the colors, the massing, the height seems… corporate and very fish-out-of-water.”

Although LaPlace’s assertion may have felt accurate in 2022, Hobson’s environs will have greatly changed by the time it is completed in August 2027. By that time, “central campus” will no longer only refer to the cozy brick of Brown Hall, Jones Hall, and McCosh Infirmary. The neighborhood will include the angled stone panels of the new Princeton University Art Museum, the roman-brick Frist Health Center, and the perforated steel facade of the Class of 1986 Fitness and Wellness Center. Although this picture might frighten our school’s more skeptical contingent, I very much look forward to seeing it actualized.

In stark opposition to the alleged “cultural and architectural decline” underway at Princeton, I firmly believe that the university is experiencing an architectural renaissance. We find ourselves in the midst of tremendous growth in built space — a staggering 2,381,700 additional square feet. As a result, critical evaluations of style, feel, and function have reached the forefront of the institutional conscience, producing architecture with refreshing candor. Yes, at times, this architecture disregards the past, but not callously — instead, with a firm conviction to materialize the communal and academic ideals of the present, set in brick and mortar.

Robert Mohan is a junior from Phoenix, Arizona studying Art & Archaeology (History of Art). He can be reached at robert.mohan[at]princeton.edu.