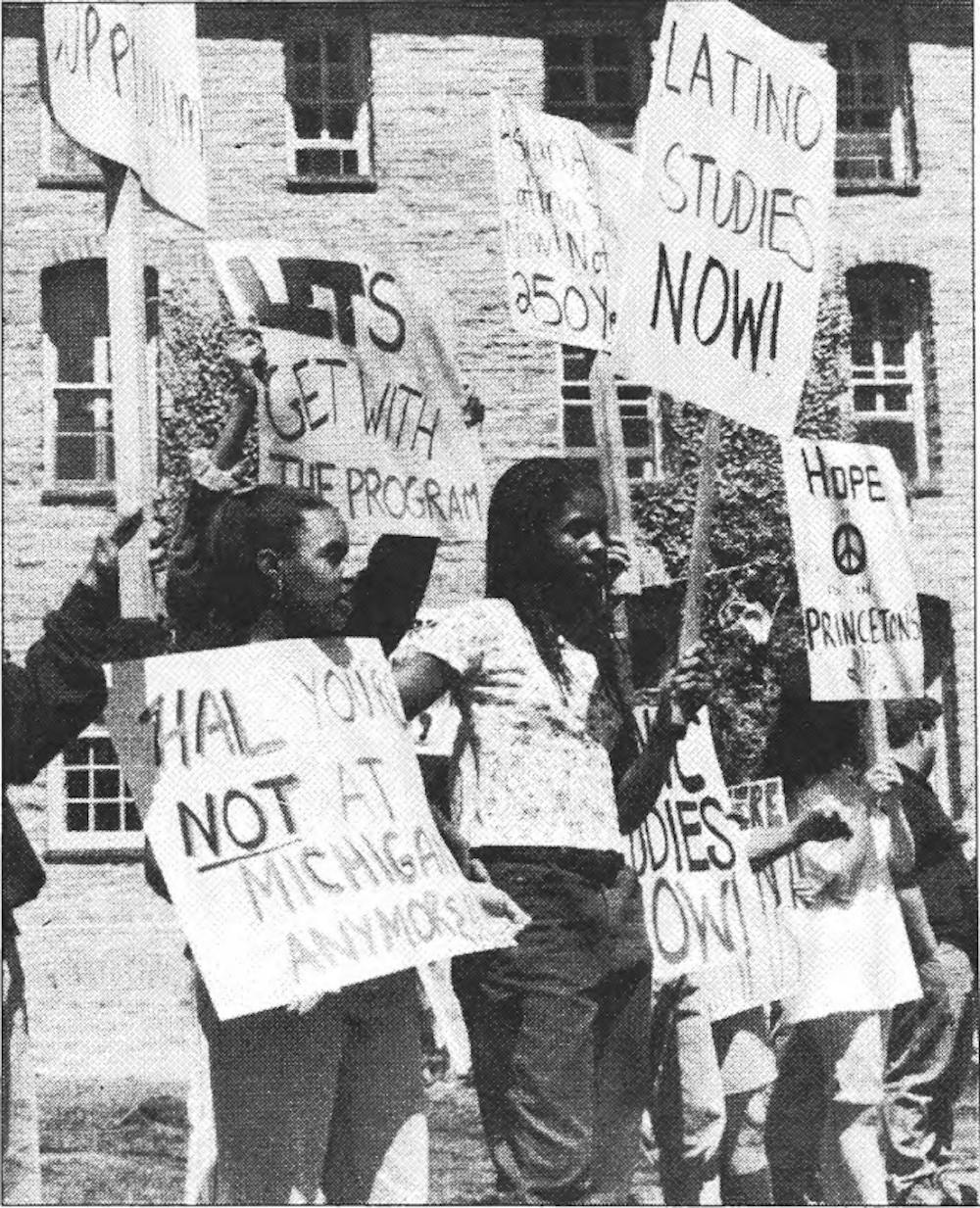

At 11:40 a.m. on April 20, 1995, a group of 17 students stormed Nassau Hall and began a sit-in to protest the lack of diversity in Princeton’s curriculum. The group decided to occupy the room adjoining the office of then-University President Harold Shapiro ’64 after realizing the main office was bolted from inside.

Their list of demands, directed toward the University administration, included “the hiring of faculty to teach Asian-American and Latino studies, increases in related library holdings, the addition of courses to the university curriculum and the establishment of a Center for Ethnic Studies.”

When explaining the motivations behind their protest actions, April Chou ’96, a participant in the sit-in, told The Daily Princetonian, “I think what led to the sit-in was a recognition that we had exhausted the efforts of working within the system to really make change.”

“We saw our efforts as a way to really bring attention to issues that matter and to really try and create further momentum towards institutional change,” she added.

According to a ‘Prince’ article written at the time, the protest group comprised a “coalition representing the Asian-American Students Association, the Chicano Caucus, Acción Puertorriqueña and unaffiliated students.”

Rebeca Clay-Flores ’97, another protest participant, explained, “I think the administration was surprised at how diverse the group was. Because we were like all the races represented.”

April Chou described their efforts as “multiracial, multi-class [years], a mix of undergraduates and graduate students and a real coalition of students who were involved.” She noted the significance of this collaborative effort, explaining, “It’s really about a broader set of concerns related to diversifying the curriculum, the faculty and the courses we got exposed to as students.”

At the time, Shapiro issued a press release which characterized the sit-in as an “inexcusable occupation of university office space.” In the statement, he also described the student's actions as “deeply offensive (to him) personally” and constituted a “clear violation of university policy.”

In turn, he was “not willing to discuss (the diversity of the curriculum) or other issues.”

Gary Chou ’96, one of the protesters’ spokespersons, shared an explanation for Shapiro’s reaction. “You see this when people are more concerned about the tone you take with something than the message of what you’re attempting to deliver,” he said.

“[The protest] was something that was very important to a small group of people, moderately important to a larger group of people and not at all important to a significant number of people as well,” said Peter Horn ’97, who helped organize and provide meals for the protest participants.

Much forethought and attempted collaboration with administration preceded the protest. Gary Chou explained that students had tried to “work through proper channels to lead the University into a better place.”

For example, in 1993, the Asian American Task Force, comprising a group of undergraduate and graduate students, published a 22-page document titled “Preliminary Proposals and Recommendations on issues related to the Princeton University Community” after consultation with students, faculty, and administrators.

Only after the students saw that their efforts were disregarded by administration did they rethink their approach. “I don’t think anyone who chooses to protest is making a decision very lightly to just jump in and do that,” Gary Chou noted.

He continued, “I think few people realize how much love actually plays into the decision to protest. I think people tend to think protest is a thing that you do when you’re mad and angry, and there’s a negativity associated. [If] people are willing to sacrifice to put a target on their back in the service of improving something, they must care deeply about this thing.”

Reflecting on responses to their protest, April Chou added, “We were extremely grateful and also felt a deep sense of solidarity because the student body came out to support the effort.”

The sit-in ended 36 hours after it began, with the demonstrators declaring victory that night after University administration had issued a written commitment to a focus on developing the Asian American and Latino Studies programs. Tangibly, it pledged a fund of $6 million, previously dedicated to the American Cultures Initiative, to the exclusive hiring of two to four faculty with expertise in these fields.

“I don’t think the University has committed itself fully. I haven’t seen enough results,” Jane Liu ’01 told the ‘Prince’ four years after the sit-in. Liu noted that it had taken the University a full four years to make its first Asian American Studies hire, Grace Hong — a specialist in the department.

On the other hand, Nancy Malkiel, a professor emeritus of History who served as Dean of College from 1987-2011, argued that changes and developments were made in the ethnic studies department, but they just “weren’t made known to students.”

Still, in 2015, some students continued to express that faculty hiring in Latino Studies and Asian American Studies was insufficient. In an article in the ‘Prince,’ Briana Christophers ’17 wrote that “with so few courses being offered and variation between semesters, there’s no guarantee that a student will be able to take a course in the future if it isn’t offered” in the Latino Studies department.

Christophers also pointed out that there was still no program in Asian American Studies. Evan Kratzer ’16 explained that the University had not “charged any department with the development of the program.” Instead, their main proposal for change was hiring more faculty for the program.

Since 1995, with the pressure of student and alumni activism and advocacy, the University has developed programs in both Latino studies and Asian American, in 2009 and 2018 respectively, through the Effron Center for the Study of America. This coming fall, the University will offer 9 LAO courses and 6 ASA courses.

Reflecting on the present, Gary Chou noted, “I have a lot of respect for the students in the more recent era. “They are addressing much more immediate and harder problems in a lot of ways, and that’s super hard,” he explained.

“I recognize that the University has to balance the importance of freedom of speech and the safety of community members,” added April Chou, but emphasized her belief in the importance of protest. “I think there needs to be room for the deep history and the important role of students and community members... being able to stand up and give voice to their values and beliefs."

Ifeoluwa Aigbiniode is a staff Features writer for the ‘Prince.’

Amy Park is a staff Archives writer for the ‘Prince.’

Please direct any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.