Campus Club, as students know it today, is a forum for student groups to convene for Undergraduate Student Government (USG) study breaks. But the site where students sip on Coffee Club seasonal lattes was once a tap room, where members and their guests danced into the early hours of the morning. The dining room on the first floor where students gather with friends to pore over problem sets was once where Campus Club members assembled for meals.

In 2005, Campus Club closed its doors due to economic difficulties, as one opinion writer eulogized, “Death comes quietly on the Street, with a few souls sitting by lamplight while parties down the block swing into full.”

Today, the Cloister Club may be facing a similar fate. “CRUCIAL: SAVE THE INN,” is how the Board of Governors of Cloister Inn began their email to Cloister alumni, calling upon them to participate in a fundraising drive to stay open.

“In order to stay open through next year, we need to raise $250,000 by the end of this school year,” the Board of Governors wrote. Cloister officers have since denied that the club is at risk of closing.

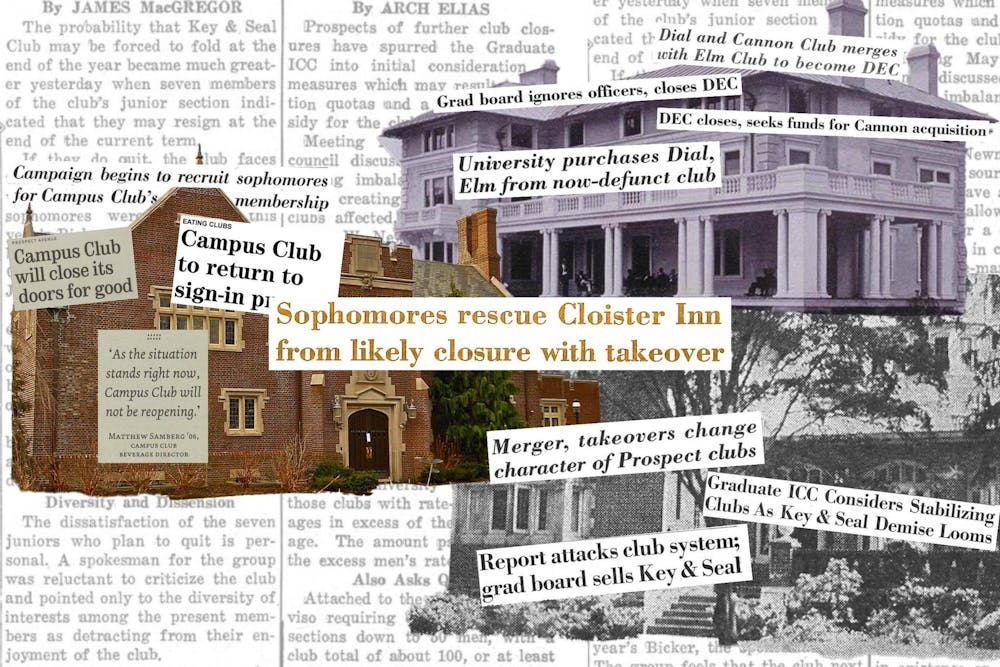

Yet the challenges Cloister faces today are not new to Prospect Street. While the composition of the street has remained unchanged since the 2011 revival of Cannon Dial Elm club, the history of the eating clubs is one of ups and downs, clubs closing their doors and bursting onto the scene, and classes flocking to clubs in takeover-style operations to make a house their home. Specifically, sign-in eating clubs have struggled.

To put Cloister’s situation into historical context, The Daily Princetonian took a close look at two successful club takeovers — both at Cloister, in 1985 and 1994 — and a cautionary tale of a club that was forced to shut its doors — Campus Club in 2005. Through archives and conversations with members involved in these takeovers, we found that clubs can be pulled back from the brink with intersectional community and pure passion on the part of prospective members — but with indecision and a lack of vision, commitment, or will, clubs can also be erased off the map.

1985 takeover leads to Cloister renaissance

In February 1985, the night that bicker results were released, a group of sophomores plotted to take over Cloister.

“We were gathered around drinking from a bottle of Old Crow whiskey the night after bicker [saying] like, ‘What are we gonna do?’” Mitch Metcalf ’87 said. “I believe it was John Marshall [’87] who said, ‘Let’s just take over Cloister.’”

In the mid-1980s, Cloister was on thin ice. With membership numbers dropping to below 20, the club’s graduate board made the decision to close the club unless there was an influx of new members.

“There was all kinds of interesting stuff going on,” David Bihl ’87, another leader of the takeover movement, said of the mid-1980s on the street. “I think Cottage had given up and had decided to go co-ed, and I think Ivy and Tiger [Inn] were sticking it out.” Ivy and Tiger Inn did not go co-ed until 1991, after notable lawsuits from Sally Frank ’80 decided by the New Jersey Supreme Court.

“There were three types of people in our class … you had the people who wanted to bicker a very exclusive club, might be Cottage, Tiger [Inn], and basically had an in … You had the folks who just rejected the bicker process and swept up the [sign-in clubs] that were in at the time … And then there was a third group, which a lot of [the takeover group] fell into, we wanted to bicker, but we really didn’t have an in,” Metcalf said.

Bihl reflected upon his initial motivation for joining Cloister, as part of a wave that ultimately kept it alive.

“The membership was so low, that made it an attractive target. We had enough people to have an impact and to have a say in the kind of club we wanted to do,” Metcalf said. Bihl remembers the membership of Cloister before the takeover being about ten people.

About 15 students who got hosed, meaning rejected from all clubs they bickered, formed the initial group behind the takeover effort. The Cloister graduate board had set a target of 40 new members putting down a $500 deposit by the end of the 1984-85 academic year and 65 new members signing up for full meal plans. The takeover group met both targets.

Bihl recalled how the early recruitment effort focused on those who were hosed from Ivy, Cottage, and Tower and failed to sign-in to Elm. They then turned their efforts to their friends who were not in eating clubs.

“Me and John Marshall, who ended up being the president, knew each other from the sailing team. We got a couple of sailors, but it was really sort of John’s roommates, a lot of people from Mathey, who they all knew, and a lot of people we had just met from the bicker process that we thought were cool people that didn’t get a bid,” Bihl said.

Metcalf and Bihl would room together with fellow takeover leader Marshall, who ended up being Cloister President, and David Jackson ’87 in their senior year.

After the takeover, debates immediately emerged over whether Cloister should keep its momentum by switching to the bicker process, which Bihl supported.

“Our thought in changing to a bicker club was stability,” Bihl said. “Who wouldn’t want to pick the next members to be part of your club?”

Metcalf took a different view on bicker, saying that the club was not ready to compete against other bicker clubs on the street.

“It’s like, look what we’ve done … Now [Cloister] is thriving, and we’re ready to play in the major leagues, and we’re ready to battle Ivy Club. It’s insane, it’s just a dumb thought,” Metcalf said.

Ultimately, internal disputes among Cloister’s new members prevented the club from abandoning the sign-in process.

“I think the non-bicker folks thought the [bicker] folks were just completely delusional, and perhaps drunk with power. Sanity prevailed, and [Cloister] didn’t go down that route,” Metcalf said.

“There were some people who were violently opposed to [bicker], and they basically said, ‘if you switch to it, we’re out,’” Bihl said. “We talked about bicker and hot tub originally, and we couldn’t even get the [original] 40 to all agree to bicker.”

In the fall of 1985, Bihl said just one member from prior to the takeover remained, reflecting hostility from Cloister’s old members towards the newcomers. Cloister’s current leadership has insisted that this will not happen if there’s a takeover in the upcoming spring, with the president Alexandra Wong ’25 writing in an email to members that current members will not “be pushed out from club culture” as a result of a potential club takeover.

Metcalf speculated as to why Cloister has been on the brink of closure numerous times in the last few decades.

“The look of the club, when you see it from the outside … it looks like the most haunted of the clubs,” Metcalf said. “You know, we’ll probably be having this conversation in 2040. Mark your calendars.”

Cloister is taken over again in 1994

Less than a decade after the previous takeover, Cloister again found itself with low membership in the early 1990s. In the midst of renewed speculation of whether the club could stay alive, a group of almost 100 sophomores banded together and took over Cloister yet again in 1994.

The ‘Prince’ sat down with four Cloister officers from the takeover group and the following class: Paul Hanson ’96, Josh Conviser ’96, Trey Tate ’96, and Amy Pannoni ’96. Hanson and Conviser helped lead the takeover effort and served as President and Vice President of Cloister for the 1994–95 term, while Tate and Pannoni served as President and Vice President the next year..

Cloister’s low membership at the time once again made it an attractive target for sophomores to take over.

“[There were] maybe 20 or 30 in the Senior class of ’94s, and then maybe seven or eight juniors from ’95,” Hanson said.

Conviser spoke about the sophomores’ mindset as Street Week approached, “It went from being like, ‘Oh my God, are we going to have to bicker and do this whole process and try and schmooze people?’ Or can we just take over and do our own thing and have this awesome group?” Conviser recalled.

Above all, the 1994 takeover group was motivated by a desire to build a new community with new traditions within the existing structure of Cloister.

“It was the control and turning it from an exclusive process to an inclusive process,” Pannoni said. “That was our pitch — everyone can be a part of this.”

“[We] created our own traditions, which I think some of which still exist to this day. We revamped everything and customized it to what our vibe was,” Hanson said.

This second takeover group is closely associated with the birth of Cloister’s “floaters and boaters” stereotype. Today, the walls of the Cloister pool room are populated with dozens of portraits of Cloister alumni from this era who have represented their country at the Olympics, most of whom competed in rowing or swimming events. Conviser, Hanson, and their roommate David Digilio ’96 were all on the crew team at various points and helped recruit their teammates to join the takeover effort.

“Ivy, up until our year, had traditionally been the swimmer club,” Tate said. “For whatever reason, Ivy decided to hose them all [in 1994]. So they joined Cloister.”

Former officers highlighted how the takeover group drew from all sections of campus.

“It was actually a pretty diverse group. We had substantial contingents from two or three singing groups, we had a lot of student government people, we actually had a lot of ‘Prince’ people … There was a heterogeneity to it,” Hanson said.

The Cloister takeover was successful, and soon demand outpaced space in the club. Future classes had to be smaller to accommodate the large class of 1996. To ensure that the few spots for future classes went to those most passionate about Cloister, the officers chose to move their sign-in window ahead of bicker and other sign-in clubs, to the chagrin of the Interclub Council (ICC).

“I was the president the second year, and I had to go to the ICC myself and say, ‘We’re going first again,’ and they were like ‘Like hell you are.’ That was ugly,” Tate said. Tate recalled how early sign-ins helped Cloister deal with high demand — if students were turned away due to a lack of spots, they could still bicker or sign-in to other clubs.

The ICC placed the club under an embargo for doing early sign-in, removing it from the interclub meal exchange program. It would only be added back in 1997. In the following years, other clubs would adopt early sign-in as well.

Just like the 1985 takeover participants, the Cloister class of 1996 recalls their time in the club as one of the happiest of their lives.

“My favorite memories from Princeton are the people I met at Cloister and are still friends now,” Pannoni said.

“Of the four of us on this call, two of us are married to other Cloister people,” Conviser said.

Campus Club sputters in the early 2000s, ultimately closing its doors

Not all clubs were saved from closure through takeover efforts. After years of speculation over its future, Campus Club closed its doors in 2005.

At the foot of Prospect, Campus began to experience difficulties with dwindling membership. Campus’ incoming class fell to about 50 in 2001 and continued to decline as the decade progressed.

To address this, Campus Club started recruiting earlier in the academic year.

“What we are aiming to do is to identify sophomores that are enthusiastic about Campus,” then-Campus Club President Dan Hantman ’03 told the ‘Prince’ in 2003. “The goal is to get people to think about committing to Campus early. That way, they can be involved in club activities sooner and get to know each other better.”

The early sign-in process failed to boost membership numbers, and Campus Club ditched sign-in entirely in May 2003 to go bicker for its 2004 recruitment process.

“My frank opinion is that [bicker] will increase and improve the club's reputation,” Campus Club Graduate Board president Lou Emanuel ’51 said to the ‘Prince’ at the time of the change.

The switch to bicker to boost the club’s reputation failed. It led at least one member to leave: in a 2004 guest contribution to the ‘Prince’ titled “When Campus Club went bicker, I went for the door,” Caroline Baker ’04 described how remaining a member of Campus would require her to “submit to an institutionalized system that is designed to reject undesirables just as much as it is to accept desirables.” She said she wanted no part in it, and left the club.

Although Campus didn’t have a successful takeover like Cloister, the idea of sophomore groups joining en masse had been floated around two years before it switched to bicker. In 2002, an email sent to numerous cultural affinity groups proposed that students belonging to racial minorities join Campus Club — though the leaders of the effort dismissed labeling their efforts as a “takeover.”

“The term takeover has been misconstrued as a political statement and movement, which is not the goal of the original people joining," said Hassina Outtz ’04 to ‘Prince’ at the time. Outtz was one of those who helped recruit new members to Campus.

The push to create an eating club for racial minorities drew pushback from some of those recruited to join the effort.

“An exclusive Latino/Black/Asian/etc. eating club would be no more than an obvious consequence of the self-segregating tendencies of this university,” Fernando Montero ’05 wrote to the Chicano Caucus listserv in response to the recruitment effort.

Takeover or not, Campus Club was a predominantly Black club in its final years. Matthew Samberg ’06, the final beverage chair of Campus Club, wrote in a guest contribution to the ‘Prince’ in 2005 that “about half of Campus’ members were African-Americans or members of the Black Student Union,” with much of the remaining half being part of the Princeton University Band.

All students who bickered Campus in 2004 were accepted. In January 2005, the club returned to being sign-in. Only a dozen sophomores joined. Campus Club announced that it would close in May 2005.

After the announcement, a group of students attempted a takeover effort to revive the club, similar to Cloister in 1985. They proposed making the club “dry” by no longer serving alcohol at parties — though members would be allowed to bring outside alcohol to the club. This would have the effect of creating a space for students who do not drink, as well as lowering membership dues.

In September 2005, weeks after the dry takeover effort began, the Graduate Board of Campus Club announced that the proposal was not feasible and the club would close its doors for good.

The demise of Campus came about after years of indecision over its future. After experimenting with bicker, the club realized that the polarizing process had an effect of pushing out members more than drawing in new ones. It dismissed attempts for takeovers or rebranding, only coming up with a proposal when it was too late. Campus Club was bought out by the University and reopened as a study space in Fall 2008.

The final presidents of Campus did respond to requests for comment.

A pattern of closure with sign-in clubs

A consistent theme of our conversations with alumni was the boom-and-bust cycle endured by sign-in clubs. To see if their observations were grounded in reality, as well as to gauge general eating club participation over time, we pulled data on the number of graduates of each eating club since 1980 from TigerNet. The data shows that overall eating club participation has declined from a peak in the mid-1990s, fueled by a decline in sign-in club membership.

Eating clubs tend to consider takeover efforts, changes to selection, or closure when the number of their graduating seniors dips to around 2 percent of the class. This is the level at which the Cloister takeover occurred in the mid-1990s, Campus went bicker, and Charter solicited takeover proposals in 2020. In 2022, just 1.6 percent of the graduating class identified themselves as members of Cloister.

The sign-in club boom-and-bust cycle is evident from the data. Colonial and Quadrangle in particular have had dramatic shifts from year to year, with membership rising to near or above 10 percent of the graduating class in some years before falling to 3 or 4 percent. Terrace has had more consistent membership, while Cloister has been in a slow but steady decline since the 1990s. Charter has also experienced large changes year-to-year — though not to the extent of Colonial and Quad — but has entered a period of stability following its successful 2020 takeover.

Even after takeovers, recoveries in membership can be temporary.

“We revitalized a club and transformed it, at least for a bit,” Metcalf said of the 1985 takeover. “All of this stuff is temporary because there seems to be a definite cycle to the clubs of a certain class.”

Among bicker clubs, membership levels have been relatively stable.

The most dramatic shift among bicker clubs can be seen in Tower’s membership, which fell from between 6 and 7 percent of the graduating class in the 1980s to just above 3 percent in the 1990s. Interest in Tower surged in the 2000s, peaking at over 10 percent of the graduating class in 2009. In the early 2010s, membership collapsed, though it began to recover in the middle of the decade.

Ivy and Cap and Gown have gradually grown, while Cottage has declined since the mid-2000s. Tiger Inn’s membership has been somewhat erratic, while Cannon Dial Elm has been relatively stable since its revival in 2011.

The stability bicker seems to bring has been attractive for sign-in clubs looking to switch to bicker.

“When the membership fluctuates year after year, it’s not always good for the club,” Hantman told the ‘Prince’ in 2003. “By keeping the admittance rate consistent year after year, finances will eventually even out and the club will have to worry less about what it can and can’t do each year.” As seen, this experiment in bringing stability to Campus failed.

When examining eating club participation on the whole, the TigerNet data shows that the proportion of seniors graduating as members of eating clubs is about the same level as it was in the mid-1980s. This level is almost 26 percentage points below the peak of eating club participation in 1994, however.

As eating clubs gradually went co-ed over the course of the 1980s and early 1990s, participation surged. In 1980, less than half of seniors graduated as part of an eating club, while almost 85 percent did in 1994. Over the course of the 1990s, participation fell, with 63 percent of seniors graduating in eating clubs in 2001. This percentage has remained relatively constant since, though the impact of individual events can be seen. In 2021, for example, less than half of seniors graduated in eating clubs, the lowest proportion since 1980, a phenomenon that can be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data reveals a seeming contradiction: while street week participation has risen, fewer seniors are graduating as part of eating clubs. This would suggest that students who do not receive spots in bicker clubs are not joining the sign-in clubs they are placed into. This explanation is supported by our recent analysis of Cloister’s 2023 recruitment cycle, in which of the 86 new members Cloister accepted, just 18 joined.

Increased alternatives to eating clubs may have also played a role in the decline in upperclassmen choosing to eat their meals on the street.

“I don’t think Independent was a big deal yet,” Bihl said. “There were some people who wanted to save money, but there were pretty few of them.” He recalled how the vast majority of the class of 1987 was in eating clubs as there were fewer alternatives.

“The options have also grown,” Hanson said. “There were no four-year colleges. You went into the upperclass housing after [living in one of] the five residential colleges at the time, and really your only alternatives were to be an RA, to live in Spelman and cook for yourself, or there’s like, two dozen people in 2 Dickinson [co-op]. I think that was it.”

When combining these two sets of data, this narrative becomes clearer. The decline in eating club participation is driven by the decline in sign-in club participation.

In 1994, when overall eating club participation peaked, 44 percent of seniors graduated in sign-in clubs and 40 percent in bicker clubs. In 2022, the proportion of seniors in sign-in clubs halved to 22 percent, while the percentage in bicker clubs remained relatively unchanged at 37 percent.

Part of this decline is a function of there simply being fewer sign-in clubs on the street. In the 1990s, there were seven sign-in clubs: Campus, Charter, Colonial, Cloister, Dial Elm Cannon, Terrace, and Quadrangle. With the closure of Campus and the closure and reopening of Cannon Dial Elm as a bicker club, there are just five.

Past officers urge sophomores to revive Cloister

At the end of our conversations with those involved with Cloister’s past takeovers, we asked them what advice they would give to the class of 2026 as Cloister entertains their takeover proposals.

“Bicker and selectivity,” Bihl said. “I think in Cloister it’s particularly important to have stability because it just doesn’t have the ability to have a large [membership].”

“Treat it like a passion, treat it like you’re saving a club, because you are, you’re saving an institution,” Metcalf said.

“How many college kids are going to get to walk in and have the opportunity to run a multimillion dollar business?” Tate said. “If you’re an entrepreneurial group, you can make it whatever you want, but you’re also getting really valuable business experience.”

Eating clubs invest hundreds of thousands of dollars to build their endowments. Some clubs have even marketed investment experience to potential members. Colonial Club maintains Colonial Investments, a group that manages over $100,000 in investment funds, and has recruited sophomores to join the group as junior analysts through listserv emails.

Pannoni urged sophomores interested in launching a takeover proposal to start now.

“It takes time to get excitement going … you don’t have to find 100 of your friends. You just need to find groups of people,” Pannoni said. “[2026] is a class that has a really unique opportunity that probably won’t come up again.”

Since its initial email to alumni, the Cloister Graduate Board has insisted to current members and the entire Princeton undergraduate community that it can operate indefinitely regardless of membership levels. However, the risk still exists that it could join the likes of Campus, Dial Elm Cannon, Key and Seal, and other clubs that have been forced to shut their doors. Cloister being pulled back to the brink raises new questions over whether there is a linked fate between the clubs that line Prospect Street — and whether the University has any role in ensuring their survival.

Former Chair of the Graduate Interclub Council (GICC) David Willard ’60 spoke to the ‘Prince’ in 2002 about the difficulties facing Campus Club. His words ring true today as Cloister’s future is on the line.

“Survival of clubs is a very important matter. To lose even one club could be detrimental to the entire system.”

Ryan Konarska is an associate Data editor and staff News writer for the ‘Prince.’

Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.