“Of course, we took the robes off to race,” John Miller ’73 said. “The only thing I had on was a pair of sunglasses.”

It was 1971. Miller and Romerio Perkins ’74 had been drinking for a few hours after skipping class. By 1 a.m., the two stood in silk robes before a rowdy crowd of students.

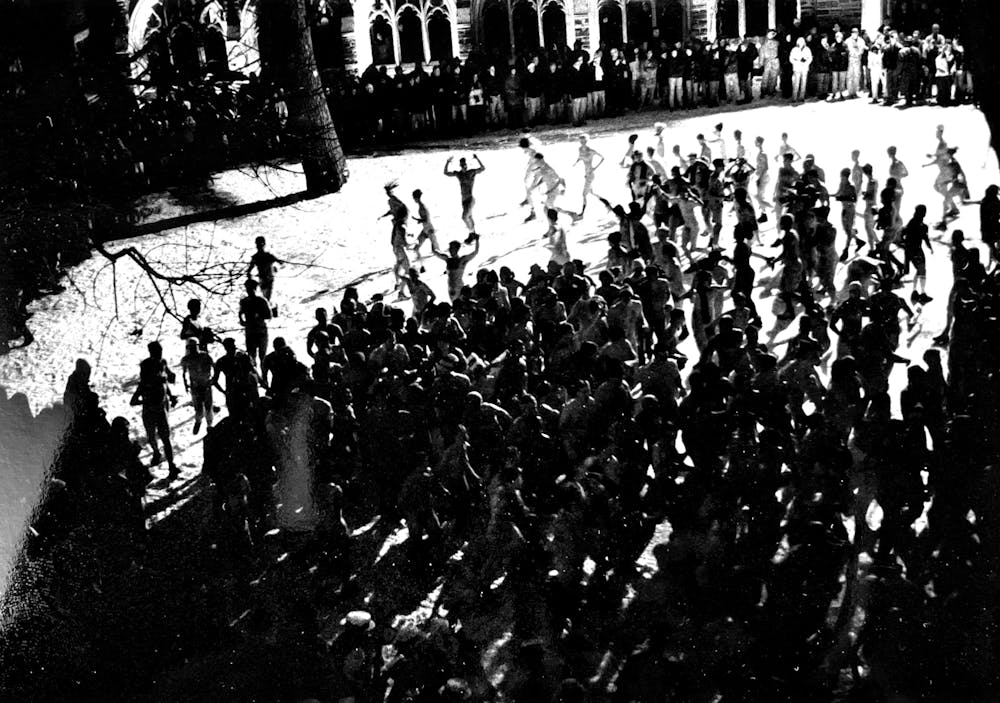

Spectators lined the edges of the Holder courtyard on both sides of a roped-off 50-yard stretch ahead. Half a dozen referees milled about, ensuring nothing got out of hand, but didn’t interfere. And then, the race was off.

“I don’t know how word got out, but it really did spread,” Miller said.

It was the first Nude Olympics, an ad hoc drunken athletic event that would blossom into an established winter-time tradition on campus. Over the next few decades, hundreds of sophomores participated each year, stripping in Holder Courtyard on the night of the first snowfall.

“I think that was really the start of it all, it was totally spontaneous,” Miller said. “It really did become an institution.”

The Nude Olympics lasted for nearly thirty years, peaking in the 1980s and ’90s. According to Heidi Anderson ’94, there were even t-shirts made featuring censored stick figures to celebrate the occasion.

“By the time I was there,” Donna Riley ’93 said, “[there were] hundreds of people in the Holder quad naked, doing calisthenics.”

In the days before cell phones were commonplace, word of the event was spread by mouth and landlines. In some years, there was a torch-bearer or trash can Olympic flame.

But for the most part, the logistics remained simple — the night after it first snowed on campus, willing sophomores showed up to Holder courtyard for the festivities, preferably wearing as little as possible. The unpredictability of the first snowfall, for many students, was part of the tradition’s fun.

“If that means you’re going to have to find a way to do Nude Olympics on a Monday night when you’ve got a paper due on Tuesday morning … it’s something to work around,” Kirk Palmer ’89 said. Palmer was a Holder resident as a sophomore.

“People from all over campus did come to participate, but [there was] a little bit of an extra incentive if you were a local,” he added.

Over the years, the tradition grew ever more riotous. Michael Jennings, Professor of Modern Languages Emeritus, was the Master of Rockefeller College –– the role now referred to as Head of the College –– from 1990–1999 and influenced the ultimate ban of the Games.

“Students think, ‘if it’s a Princeton tradition, it must have started in 1760.’ This didn’t start in 1760,” Jennings explained. “It started in a big way in the late 1980s, where large numbers of students, and for the first time, women, started to participate.”

But the tradition died before the turn of the century as administrators grew increasingly concerned with excessive drinking at the event, along with disreputable student behavior and safety risks concerning female participants. Threats of suspension discouraged participation, and the Nude Olympics quickly turned from legacy to legend, now prompting stories — but no streaking — as the first snowflakes land each year on campus.

Forging the naked path

In 1980, The Daily Princetonian reported that “30 of the nation’s finest men [were] gingerly doing jumping jacks in the snow,” after lighting an “eternal flame” in a garbage can at the center of Holder courtyard.

The more determined participants made the event into a full athletic competition. By the late 1980s, the Games included wrestling, jumping jacks, sit-ups, push-ups, and wheelbarrows. Other students, like Anderson, preferred to run around and streak rather than take a calisthenic-intensive approach.

Often, the naked Olympians would leave Holder courtyard. Palmer, who participated in 1987, said the festivities regularly extended into Firestone Library later in the night.

“That was especially fun … to interrupt the people who [were] studying, run past them, and maybe do some jumping jacks in the library,” he said.

Some of the unclothed athletes even made their way onto Nassau Street. J.B. Winberie’s restaurant and bar was a common destination for runners to wreak scenes of havoc and disorder. The Class of 1994 had to reimburse the eatery $1,500 for incurred damages after their Nude Olympics night. The next year, over thirty participants were arrested for disorderly conduct in town.

Jamison Abbott ’96, who broke tradition and participated as a first-year with some fraternity friends, spent the night following the Nude Olympics in jail.

“About 50 people ended up in the Wawa, and it was chaos,” Abbott said. “They were knocking shelves over and throwing stuff, and it was pretty bad.”

Abbott was arrested with another first-year for stealing a banner, wall clock, and gallon of ice cream from the store. He pled guilty to shoplifting and disorderly conduct and was ultimately hit with a fine and 30 hours of community service.

He returned home for the winter holidays a few days after being thrown in a police car. When he finally came clean to his parents, the news didn’t come as a surprise — it was already reported on the radio.

Going co-ed prompts safety concerns

Although there was never an official gender restriction on the Nude Olympics (the only qualification was being a sophomore, preferably intoxicated), the first few classes of naked frolickers were all men.

The first year that saw major female participation was 1987, a shift covered by the ‘Prince,’ which garnered mixed reactions from male and female students alike.

“Women always have the right to run naked in my backyard,” Holder resident Mark Rubin ’90 told the ‘Prince’ in the 1987 article. “I'm no chauvinist.”

Others saw female participation in the games as contradictory to recent feminist organizing campaigns against pornography. Still, many looked positively on the co-ed participation.

“I understand the issues around gender equality [and] people being uncomfortable, but I felt like [ours] was pretty good, clean, fun,” Palmer added.

Anderson recalls that women were well–represented at her Olympics in 1991 — the same year that Tiger Inn became co-ed as a result of the Sally Frank ’80 lawsuit that reached the New Jersey Supreme Court. The previous fall, Ivy Club had accepted its first women as well.

“Things were more equality-based. None of us felt threatened, or [none] I personally [knew] of,” Anderson added. Though she didn’t recall problems with the activity itself, Anderson noted naked groups gathering around dormitory entrances made residents feel uncomfortable since key card locks had been placed for the first time on entryway doors, adding obstacles to entry.

Riley holds a different view. The same year, she remembers a “critical mass of women” participants, although the demographics leaned majority male and white. The over-drinking before the event concerned her more.

“For women, the Nude Olympics wasn’t a safe place to be,” explained Riley. “People couldn’t be naked without being very drunk, created this environment where groping [and] sexual assault happened. It wasn’t possible to do it responsibly with that many people.”

When she was a first-year, Riley recalls hearing of a woman in the class of ’92 who was sexually assaulted in her year’s Nude Olympics. That story, in combination with the budding tradition of the Take Back the Night March in protest of campus sexual assault, “informed [her] thinking pretty heavily on what [she] would do that night,” she said.

Riley planned an alternative sledding event in the Forbes backyard for women who wanted to enjoy the first snow without taking off their clothes or drinking to excess, borrowing trays from the dining halls.

While Anderson enjoyed participating in the Olympics, she believed that “if people drank too much or were touched too much, that does supersede all.”

“It’s frustrating when people take things to the extreme or can’t just purely enjoy it,” she said.

Ultimately, these safety concerns, combined with the increased rowdiness, led to a University-imposed ban of the Nude Olympics and for the tradition to fade from an annual tradition to storied lore.

Death of a tradition

Over the ’80s and ’90s, student behavior grew ever-rowdier, with one University spokesperson calling it “mob-like.” In 1993, the University considered setting up lights in the pathways used to deter participants from the Olympics.

Former Dean of Student Life Janina Montero began a residential college advisor (RCA) campaign in the early 1990s to warn students against dangerous behavior during the Games.

In 1992, Princeton borough police arrested over 30 students on charges of lewdness and disorderly conduct following the event. Abbott, the student arrested outside Wawa the following year, thought behavior had gotten much more out of hand by his time compared to when it started in the ’70s.

“It’s a shame it got to the point where the University had to say ‘Look, this ends now; anyone who sets foot outside naked is done,’” Abbott said.

“I wasn’t worried about liability, I was worried about students being hurt, or worse,” Jennings said, whose room in Rocky gave him a clear view of the risky consequences of the Games.

Along with Master of Mathey College David Carassco, Jennings was responsible for the letter that got University President Harold Shapiro GS ’64 to ban the Olympics in 1999. They held multiple concerns regarding the event, one of which was the growing presence of outside spectators.

When Palmer participated in the tradition in the late 1980s, he didn’t notice anyone taking photos or any outside observers. To his recollection, everyone was a student.

“Back then, you would have stuck out like a sore thumb if you brought a camera to this,” Anderson said, who participated in 1991. “If you were a freshman spectator snapping camera pictures, that would not have been received well.”

Though photography of the event was rare, the crowds were growing. The ‘Prince’ estimated that 500 spectators gathered to watch the 1991 games.

“As more students participated, and especially more women participated, the notoriety of the event began to spread,” Jennings said.

He recalls that the crowd of spectators grew over the years, expanding from only students to include adults from the community. Jennings said the audience got “creepier and creepier,” and that many men in particular brought cameras to the event.

By the mid-’90s, Abbott said, “there were definitely outside people with cameras.”

“If we lived in a world where young people could run around without clothes on and be safe, I’d have no problem with it,” Jennings said.

Student drinking also grew ever-more excessive. After ten sophomores were hospitalized for alcohol poisoning from the 1999 Olympics, administrators came out strongly in favor of stomping out the bacchanalian tradition. President Shapiro formed a committee to review recent iterations of the Games, citing concerns over alcohol abuse and student safety.

“President Shapiro is serious about stopping any event of this nature, and the trustees stand firmly behind him,” the ‘Prince’ quoted Dean of Student Life Montero as saying. “The University’s resolve is entirely unambiguous.”

The news was not received positively by everyone. In response, Al Walling Class of 2000 reportedly promised to run the following year.

“You better tell Public Safety to lay off the doughnuts, because they’re going to have to catch me,” he said.

But when the University promised a year-long suspension to anyone participating in drunken, naked events after the first snowfall, the Nude Olympic flame quickly died. Through decades of first snowfalls since, there have never been any widespread revivals of the antics.

In general, streaking and related activities no longer proliferate on college campuses the way they did in the twentieth century. With the rise of cell phones and social media, distributing photos of such activities has become easier and easier, making individuals averse to participating.

Today, the legacy of the Nude Olympics lives on through alumni sharing their stories from the event over beers and laughter at Reunions, as the curious undergraduates working at tents and pouring their drinks listen in. Although some campus traditions have stood the test of time, others, from the Nude Olympics to the annual theft of the Nassau Hall clapper, have faded to relics.

Miller looks back on the first Nude Olympics as a “college party night, one of those things that happens in one’s life.”

“Maybe they’re not the most proud events you’ve ever had, but they certainly make a good story,” he said.

Gia Musselwhite is an assistant Features editor for the ‘Prince.’

Paige Cromley is a head Features editor for the ‘Prince.’

Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.