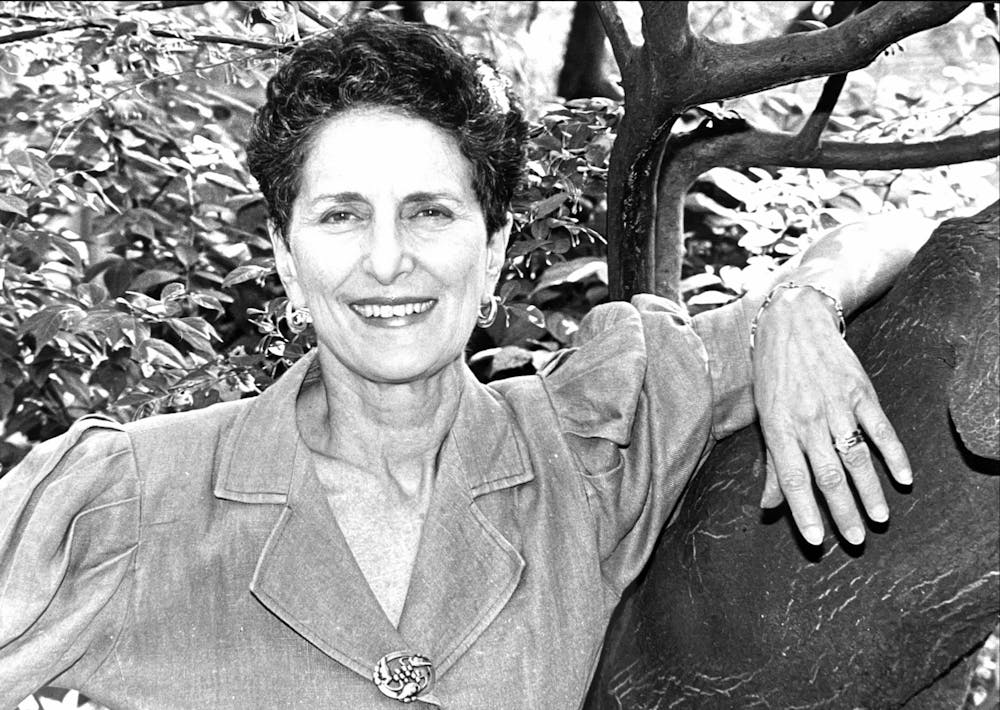

Natalie Zemon Davis, a pioneer in the study of women, gender, and the marginalized in historical scholarship, died in her home in Toronto on Saturday, Oct. 21, at the age of 94.

According to her son Aaron Davis, the cause of her death is cancer.

A renowned historian of early modern French society and culture, Natalie Davis was the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History Emerita at Princeton, where she was a member of the history faculty from 1978 until her retirement in 1996.

Natalie Davis’ scholarship focused on peasants, women, workers, and populations who were otherwise marginalized in the writing of history. At a 2019 conference celebrating Natalie Davis’ 90th birthday, Joan Wallach Scott, Professor Emerita at the Institute for Advanced Study, called Davis a “historian of hope.”

A key figure in the establishment of gender history and microhistory, Davis’ scholarship drew influences from cultural anthropology and literary criticism, as well as inventive ways of reading through archives.

Peter Brown, the Philip and Beulah Rollins Professor of History, Emeritus, spoke to the ‘Prince’ about the lessons Natalie Davis taught the history profession in reading archives.

“What Natalie did was show how archives could be used creatively,” he said. “Natalie taught us how to ask the archives why they are there in the first place. Why do people keep these things? What do they reveal when you read over their shoulder?”

Natalie Davis recognized early on in her career that women’s history could not be a historical field isolated from the rest of the discipline. Instead, she pushed for gender as a line of inquiry that studied social relations between men and women as a worthwhile historical category.

Her most prominent work, “The Return of Martin Guerre” (1983), told the story of a 16th century case of imposture in France, in which the peasant Martin Guerre seemingly returned to live with his wife after abandoning her several years earlier. When it was revealed that the person in question was actually a man by the name of Arnaud du Tilh pretending to be Guerre, he was tried and executed.

Previous historical accounts had mostly overlooked the role played by Guerre’s wife, Bertrande de Rols, but Davis made her to be a central figure who played along with the imposture instead of the unaware victim she was previously thought to be.

The book was a follow-up to a popular 1982 film of the same name in which Davis was a historical consultant to the film’s screenplay.

A movie still featuring Gérard Depardieu and Nathalie Baye in a scene from The Return of Martin Guerre, for which Natalie Zemon Davis served as a historical adviser.

Courtesy of Princeton University Archives

The granddaughter of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Davis was born on Nov. 8, 1928, in Detroit. Her father, Julian Zemon, worked in the textile industry, and her mother, Helen Zemon, née Lamport, was a homemaker.

After graduating from Cranbrook Kingswood School, Natalie Davis attended Smith College and received a bachelor’s degree in 1949. In 1948, she met Chandler Davis, a Harvard mathematics graduate student, poet, science fiction writer, and fellow leftist radical; the two married six weeks later, despite her parents’ objection that he was not Jewish.

“I’d attended a Students for [Henry] Wallace gathering, and I noticed a handsome guy holding a ping-pong paddle. I loved tennis and ping-pong, so I thought, ‘Well, that’s a good sign.’ Chan was smart, on the political left, interested in music and poetry, and he liked smart women,” Natalie Davis said in an interview in 2018. “We married the summer after my junior year.”

In 1950, the couple moved to the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor, where Chandler was offered a teaching position and Natalie continued her doctoral studies, having started them at Harvard. Natalie and Chandler Davis were married for over 70 years, until his death in 2022.

For the couple’s radical political activities and their association with Communist Party USA, the federal government seized their passports in 1952.

In a 2014 interview, Natalie Davis recalled how the ordeal placed great stress upon her as an expecting mother and graduate student who needed to travel to Lyon, France to access the archives there for her research.

Chandler Davis was later dismissed from his position at the University of Michigan in 1954 and indicted for contempt after his refusal to answer questions in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee. The event made it extremely difficult for Chandler Davis to acquire another academic job in the United States amid the political climate of the 1950s.

Natalie Davis herself did not receive her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan until 1959, and even then without a formal advisor.

The couple, in addition to raising three young children, managed to make a living by teaching part-time, editing journals, and working other odd jobs, until Chandler Davis was sent to prison for six months in 1960. At the time, the couple was living in Providence, R.I., where Natalie Davis taught at Brown University.

After Chandler Davis’ release, the couple moved to Canada to teach at the University of Toronto, which had offered him a tenure-track position in 1962. Chandler would remain here for the rest of his life, while Natalie Davis was on the faculty there from 1963 to 1971.

At the University of Toronto, Natalie Davis, together with Jill Ker Conway, who later became the first woman to be named President of Smith College, designed and taught a course focusing on the history of gender and women. Their efforts were met with objection and skepticism from some members of the faculty.

Natalie Davis joined the history faculty at UC Berkeley in 1971, and taught there until she joined the Princeton history department in 1978, in part because the commute between Berkeley and Toronto was too overbearing. The second female member of the history faculty at both UC Berkeley and Princeton, Davis played a role in establishing women’s studies programs at both institutions.

Anthony Grafton, the Henry Putnam University Professor of History, who joined Princeton at around the same time as Davis, recalled the early days of their time as colleagues in the history department.

“She was not shy. I remember we had a funny initial contact, because I was hired after she first turned Princeton down. When she decided to come to Princeton, I was already here,” Grafton recollected. “Which could have been awkward, but she walked into my office when she was at the Institute [for Advanced Study], sat down, put her boots right up on my desk and just started talking very naturally. And it just went from there.”

Grafton recalled that Davis was placed in a corner basement office of McCosh Hall for several years, and she would always offer people to come by for tea.

Natalie Davis was named as the Director of the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies in 1990, succeeding Lawrence Stone, who had led the center as its first director for over twenty years. According to David A. Bell GS ’91, the Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, who is currently the Director of the Davis Center, her leadership made the department much more welcoming to women and people of color.

For nearly twenty years, Natalie Davis regularly taught HIS 348: Society and the Sexes in Early Modern Europe, in addition to HIS 349: History of France, 1480–1685.

In the spring of 1980, Natalie Davis designed the undergraduate seminar HIS 442: Jews in Early Modern Europe (1500-1800), A Comparative Perspective, with Mark R. Cohen and the late Theodore K. Rabb. She co-taught the seminar with them until her retirement. From the primary sources assigned for this class spawned the publication of The Autobiography of a Seventeenth-Century Venetian Rabbi: Leon Modena's Life of Judah (1988), which is still assigned reading in a junior seminar taught by Yaacob Dweck, the Philip and Beulah Rollins Professor of History.

Natalie Davis also regularly taught the graduate seminar HIS 552: Religion and Society in Sixteenth Century France. According to Bell, who was enrolled in the seminar as a graduate student, Davis often took her students to her home at 78 Alexander Street and discussed history over tea and cookies.

Carla Hesse GS ’86, the Peder Sather Professor of History at UC Berkeley, remarked on the kind of teacher that Davis was, as well as how her devotion to social causes connected to her care for her students.

“She liked [my first major research paper for her] very much, but said ‘Okay, you’ve learned how to widen your lens, now learn how to move your tripod.’ That stayed with me my entire life. She wanted you to see it [the big picture] from the perspective of those who are marked most marginalized in a society.”

Hesse also recalled that when she and a group of other students were arrested and jailed for blockading Nassau Hall in the spring of 1985 in demand of Princeton’s divestment from South Africa, “Natalie Davis came riding down on her bicycle with her checkbook, saying ‘I want to bail my students out.’”

A lifelong advocate for social justice, Davis was a supporter of civil rights in her student days; her colleagues interviewed for this obituary agreed that had she been well enough to do so, she would have been outspoken about her beliefs on the ongoing conflict between Hamas and Israel.

She sustained a lasting friendship with the late Toni Morrison, the novelist and Nobel laureate who was the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities at Princeton.

Davis sought Morrison’s feedback on her academic writings as she turned her attention to studying slavery in the Dutch colony of Suriname. At the time of her death, Davis was near completion on her book, “Braided Histories,” an exploration of the Jewish and Christian slave owners as well as the enslaved Africans living on their plantations in 18th century Suriname.

In a postcard, Davis wrote to Morrison about giving a copy of Morrison’s 2003 novel, “Love,” to her daughter Simone.

“So Love,” wrote Davis, “is going down the generations.”

Davis transferred to emerita status in 1996, and returned to the University of Toronto, where she remained for the rest of her life.

Natalie Zemon Davis and Robert C. Darnton in April of 2006, at a celebration of the latter's retirement from Princeton.

Courtesy of Carla Hesse GS '86

As a celebration of Natalie Davis’ retirement, members of the history faculty dressed up as historical characters featured in her works, such as Glückel of Hameln, and — following a script written by Grafton and Sean Wilentz, George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History — playfully informed her on how she had mischaracterized them in her writings.

Natalie Davis became the second woman to ever serve as the President of the American Historical Association in 1987. Among her many honors are the 2010 Holberg Prize and the 2012 National Humanities Medal. She was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1979 and made a Companion of the Order of Canada in 2012.

Natalie Zemon Davis is survived by her brother Stanley Zemon, son Aaron Davis, daughters Hannah Taïeb and Simone Davis, four grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Allan Shen is a senior News contributor for the ‘Prince.’

Please direct any corrections requests to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.