In 1835, the College of New Jersey was on the brink of financial ruin.

“The whole of the available funds … little exceeds $2,000 per annum,” Daniel Newell, a representative of the Alumni Association, wrote in a letter called “The Case of the College of New Jersey.”

“The college prospectively is in danger, unless something is speedily done,” Newell wrote.

Newell and his fellow officers of the Alumni Association, Samuel Miller and John Maclean, Class of 1816, asked alumni to contribute $100,000 within the next year, an enormous sum that would help the college construct new dormitories, expand its library, and raise professors’ salaries. With these funds, they promised that the hallowed but fragile institution would gain a “permanent foundation.” Without the funds, they feared that the College of New Jersey would not survive.

Alumni from New York, New Jersey, and South Carolina responded with enthusiasm. Among them was David Leavitt, who offered $1,000 in October 1835 if the college would admit students “irrespective of Color” and grant them “like privileges.” His offer was enormous — enough to raise the salaries of three professors and insure a new building.

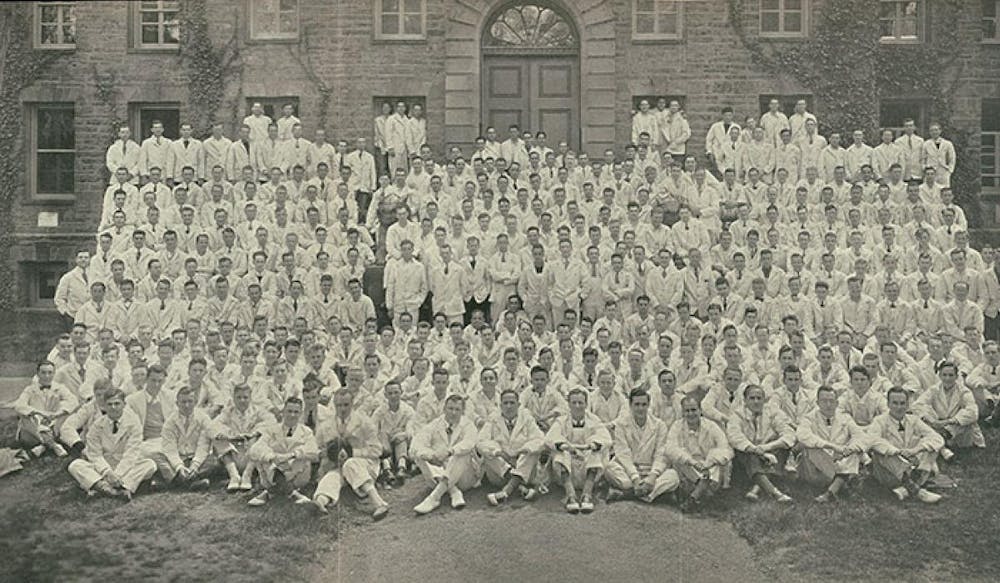

But the Board of Trustees declined it, preferring that the school remain white and Anglo-Saxon at the expense of a transformative donation. The college, now known as Princeton University, would not admit its first class of African American students until 1945.

More than a century after the donation drive helped propel Princeton into the world-class liberal arts institution that it is today, the story of Leavitt and his rebuff is now all but unknown.

***

The New York Times once described Leavitt as a “millionaire … [with] rural tastes.”

Born in Bethlehem, Conn. in 1791, he made his fortune as the president of the American Exchange Bank and the Brooklyn White Lead Company. When he was not working in New York, he was in one of his sprawling country estates across the northeastern United States.

His three hundred acres in Great Barrington, M.A., were home to the largest barn in New England: a structure of “universal admiration” that was accessible from three Gothic Revival entrances and cooled by the Housatonic River. He owned thoroughbred horses, maintained Italian-style gardens, and had an art gallery with Emmanuel Leutze’s Washington at Valley Forge hanging on the wall.

In Princeton, N.J., Leavitt stayed occasionally with his daughter and grandchildren at his family estate named Fieldhead. Photographs in his grandson’s scrapbook show a home filled with bookshelves and college memorabilia, from black-and-white banners to souvenir calendars.

According to the New York Chamber of Commerce, Leavitt was as well-known for his “active and liberal politics” as for his wealth.

On Oct. 21, 1835, he traveled to Utica, N.Y. for the first annual meeting of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, where he represented Brooklyn Heights and served as one of several vice presidents.

Declaring themselves “friends of immediate emancipation” in their First Annual Report, those at the convention pledged to “prevent our valued republican institutions from becoming a cloak to the most odious and irresponsible despotism.” They declared that all attempts to justify, preserve, or reform slavery were contrary to the Bible and human reason.

These were not moral abstractions to Leavitt. As he stood under the high ceilings of Utica’s Bleecker Street Church that morning, he might have come to the realization that Princeton was sinning against God.

Just a month before, a mob of about 60 undergraduates had marched towards Witherspoon Street, the center of Princeton’s African American community, and dragged a white abolitionist outside by the throat.

“Kick him out of town!” they screamed as they beat him into the ground. “Kick him to death!”

It was in the wake of this sobering incident that Leavitt offered part of his fortune to the college on Oct. 28, 1835, perhaps hoping that the most important institution in Princeton would renounce its entanglement with sin.

***

Yet Maclean was too entangled with slavery to consider renouncing it entirely.

At the same time that he was calling for donations to the College of New Jersey, he was also soliciting funds for The American Colonization Society (ACS), a group founded in 1817 to send free African Americans to Liberia.

Maclean had been raised in a wealthy household on the College of New Jersey’s campus, with enslaved individuals named Lydia, Sal, and Charles cooking his food and cleaning his plates. His father, John Maclean Sr., was then serving as the president of the College.

From 1824 onwards, Maclean attended nearly all meetings of the ACS Princeton chapter, rising from secretary to vice president just as he rose through the ranks of the College from professor to president. Between the college and the ACS, he was a man of parallel worlds.

When he wrote one evening in the chapter’s meeting notes that the “free Blacks of the State of New Jersey shall have the preference,” he was referring not to their admission to the College of New Jersey, but to their choice of vessel on the journey to Africa.

Leavitt’s dream would wait another 110 years.

Anna Salvatore is a senior Features contributor for the ‘Prince.’

Please send corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.