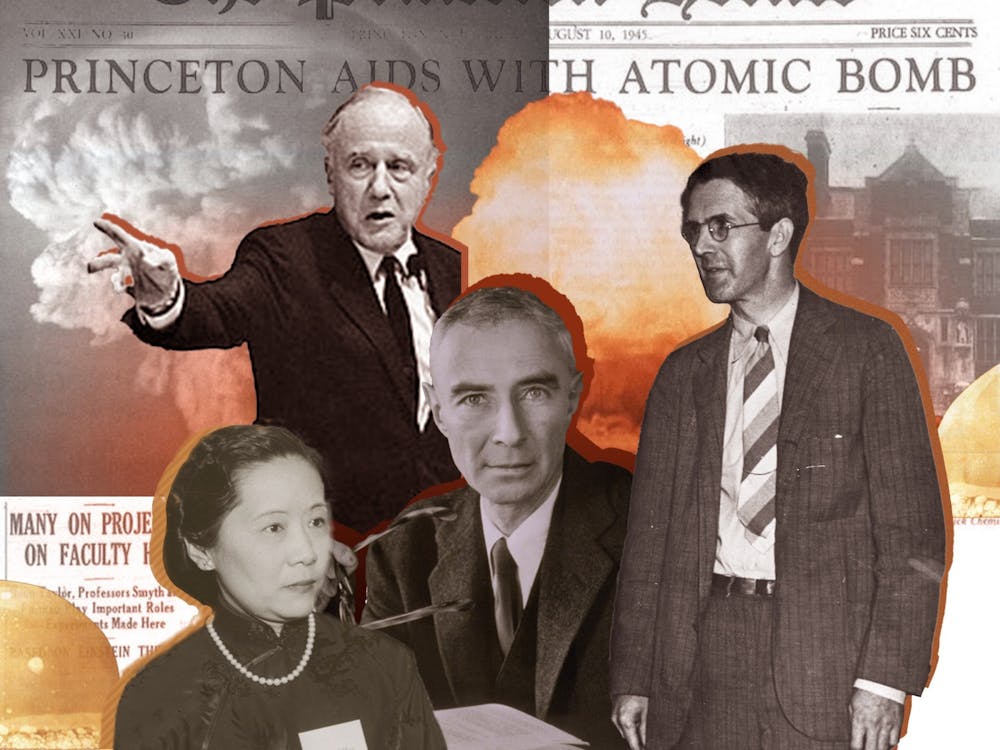

Last spring, filming for Chistopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” stirred excitement at the Institute for Advanced Study and in Princeton’s East Pyne courtyard. The 1940s-era biopic, which opened with positive reviews on July 21, invites reflection on the role University faculty members, Princeton residents, and J. Robert Oppenheimer himself played in the Manhattan Project and the subsequent development and governance of nuclear weapons.

“The big news of the week — the big news of the century — in the world of science.”

That was the front page of the Princeton Herald a few days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki took over 200,000 civilian lives, brought World War II to an end, and eternally raised the stakes of global war. The Herald covered Princeton’s instrumental role in developing “the greatest discovery in modern warfare.”

Dr. Zia Mian, co-director of the University’s Program on Science and Global Security (SGS), points to that headline as giving a crucial insight into atomic history.

“You might think that you wouldn’t be so proud of having worked on nuclear weapons, given where we are now at Princeton,” said Mian in a recent interview. “But back then, it was seen as this great thing Princeton had done. Princeton benefited afterwards because of its special role [in the project].”

Princeton’s part in this atomic history involves a range of players, from J. Robert Oppenheimer himself to the rarely-credited women who “crunched the numbers,” and the physicists responsible for the world’s first anti-nuclear non-governmental organization.

Oppenheimer at Princeton

Oppenheimer’s story stands out among those central to the Manhattan Project, the wartime operation that was responsible for the development of the world’s first atomic bomb. A faculty member at UC Berkeley, Oppenheimer is commonly attributed with helping bring quantum mechanics to America.

In 1942, he was recruited to direct the laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, which became the most famous nuclear development site to come out of WWII. The Trinity site — where the bomb was first tested in July 1945 — stood 220 miles south. Notably, the development of these sites displaced parts of the Navajo Nation and southwest Pueblo nations who inhabited the land.

Following the war, Oppenheimer surrendered the helm of atomic weapon development. Reportedly, he told President Harry Truman “[he felt he had] blood on [his] hands” when meeting him in October 1945 after the introduction of such a threat into the world and the destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

While Oppenheimer would refer to his role in the bomb’s creation as “the fulfillment of an expectation” for years to come, he championed policy regulations of atomic weapons and advised against the US government’s development of the thousands times more powerful hydrogen bomb without success.

In 1947, he was appointed with support from his future foe, Lewis Strauss, to become the third director of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey. The IAS, though officially independent from Princeton, has had a strong relationship with the University and shared library resources since its founding.

IAS Archivist Caitlin Rizzo noted that there was a scholarly cross-exchange between the two institutions through “seminars, conferences, and even positions to attract the best scholars.” Albert Einstein is also associated with Princeton through the IAS, of which he was a founding member.

Oppenheimer became an important figure in Princeton life. He lectured in McCosh 50 while bringing young scholars and new disciplines to the IAS. At the same time, he was shifting his public efforts to atomic regulation as Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)’s science advisory board.

“When you open any door in Washington, Oppenheimer’s in that room,” said Dr. Michael Gordin, a historian of science at Princeton, about Oppenheimer’s days on the board. “For that period of time, he was a key advisor to many aspects of atomic policy.”

Early connection to the development of the bomb

“Oppenheimer himself has often been discussed as ‘the father of atomic bombs,’” explained Assistant Professor of Anthropology Dr. Ryo Morimoto, in an interview with the ‘Prince.’ “But the reality is that he happened to take the leadership role of a project that involved the entire nation.”

The University’s involvement in the Manhattan Project began earlier and was far more extensive than just through a connection to Oppenheimer. The August 1945 edition of the Princeton Herald covers this complex history. This record begins in February 1941, when Princeton researchers experimented with the first steps towards harnessing the nuclear chain reaction for atomic weaponry.

Many experiments were conducted in Palmer Physical Laboratory, the home of Princeton’s Physics Department (located in what is now Frist Campus Center) and Frick Chemical Laboratory.

Gordin, who specializes in early nuclear history, commented on Princeton’s involvement in the Manhattan Project.

“Physics was a reasonably small field in the U.S., up until the 1920s. It really started to grow in the 1930s, and Princeton is one of [its] centers. It makes sense that when you’re going to recruit people to work on a physics-based project, you would [recruit] from Princeton,” Gordin said.

One of these figures was Professor Henry DeWolf Smyth GS Class of 1921, a leading faculty member in the Princeton Physics Department from 1924–1966. During the war, Smyth taught practical physics principles like mortar round trajectories and anti-aircraft targeting to US officers. Additionally, he consulted for the Manhattan Project and held membership in the National Defense Research Committee’s uranium section.

Notably, Smyth wrote a 60,000-word technical report on the Manhattan Project’s military research and use of atomic energy, with the subtitle “The Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government.” This account was released by the United States War Department on August 12, 1945, days after the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The public weight of the Smyth report “tells you the kind of trust that the Manhattan Project leadership had in Smyth and the Princeton Physics Department,” said Mian.

“[But] part of what that official history did was to tell the world the kind of science and technology the public had the right to know about. Princeton, through Smyth, played this fundamental role in establishing the barrier of the great wall of secrecy that has surrounded nuclear weapons.”

Unsung contributions

Smyth recognized eight notable Princeton researchers in his public report, including prominent physicists Richard Feynman ’42, John Wheeler, Eugune Wigner, and Robert Wilson. Many of these scholars hold renowned legacies at Princeton today for their groundbreaking achievements.

However, the men credited by Smyth are far from the comprehensive list of Princeton involvement in the Manhattan Project. According to Gordin, Princeton faculty contributed to Manhattan Project work in many ways, from particle accelerator experiments on campus to on-site work at Los Alamos and other secretive bases. Over two dozen faculty members were employed at Los Alamos alone.

“It wasn’t just famous physicists [who] went … they took their graduate students with them,” said Mian.

A few women held official research status on the Manhattan Project during the time. Two of these groundbreaking physicists were Chien-Shiung Wu and Elda Anderson. Wu was the first woman to join Princeton’s physics department faculty and made important contributions to uranium enrichment. Anderson, meanwhile, developed the first test sample of uranium-235 on Princeton’s campus.

Professors’ work at design and operation sites also often became a family affair. The wives of faculty members did not just move with them, but they were regularly employed at the sites doing calculations on key experiments.

“The word ‘computer’ used to be a job description, not a device,” said Gordin. “Almost always, it was a woman. There [was] a lot of that at Los Alamos—because of secrecy, the labor pool they [had were] the families.”

Despite their essential work, these women did not receive much credit for their part.

To this day, many other historically marginalized groups have also been written out of the Manhattan Project narrative. No African Americans worked at Los Alamos, but the facility at Oak Ridge, Tenn. was a segregated community for scientists, engineers, and construction workers alike.

“There was no effort to try and address this discrimination,” commented Mian. “All the existing social relations were just distilled down to their purest essence and put to work on a military project.”

Morimoto said that there is a record of Native people working in facilities, but only a few — like Herbert York at the Oak Ridge site — are credited in the records. Native people, like the Navajo in the American Southwest and the Deline in Northwest Canada, were even coerced into mining uranium for the project as one of the only job opportunities available to them.

“I think the challenge is to tell the alternative narratives that exist as a way to try and change the present and the future,” added Morimoto.

Concerns about nuclear weapons

In decades to follow WWII, Princeton administrators would justify the secrecy and consequences of Princeton’s involvement in the Manhattan Project as “in the nation’s service.” But the atomic bomb’s impact on society was highly contested by scientists and policy-makers, even prior to the first nuclear test at Trinity.

Oppenheimer was one of many physicists who came to fear the global implications of atomic weapons — especially elevated to the level of the hydrogen bomb — after Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrated their potential for destruction.

“In Princeton proper, there were several gatherings of those that feared [the bomb’s] development,” wrote Rizzo.

Soon, the Emergency Committee of the Atomic Scientists — the world’s first anti-nuclear organization — was born with headquarters at 90 Nassau Street. The group was founded by Einstein and fellow physicist Leó Szilárd. The Emergency Committee fundraised, wrote articles, gave lectures, and created the first documentary films about the dangers of nuclear weapons, according to Mian.

But some who contributed to the development pushed back, even denying the impact of the bomb.

Smyth and others on the project denied the lasting damage of nuclear radiation and questioned the accuracy of Japanese reporting on the catastrophe months after the war. Such damages were, of course, proven true — radiation poisoning was directly tied to massive spikes in diagnoses of leukemia and other cancers.

According to Morimoto, “there were [also] people like John Wheeler who continued [their research] thinking it was in service of nation and humanity.” Wheeler directed Project Matterhorn B at Princeton, developing hydrogen bombs for the US government during the Cold War.

Oppenheimer’s own credibility took a hit during the second Red Scare, the rampant American anti-Communist era in the early 1950s, when he was publicly humiliated in an AEC hearing led by Strauss over his security clearance. The story was covered by the ‘Prince’, with prominent Princeton scholars like physics professor Wigner taking up his public defense.

Oppenheimer died in 1967 — with a memorial held at Alexander Hall — but Oppenheimer’s legacy in atomic policymaking and nonproliferation lived on at the University. Since its inception by a group of physicists in 1974, Princeton’s Program on Science and Global Security has made global policy efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons and gather together science graduate students with a future in security policy.

Commemorating that history today

“It’s a very interesting, complicated, difficult story to tell,” says Mian. In the years since, that challenge has only fueled leaders on campus.

SGS’s current work, for instance, is focused on eliminating the culture of nuclear secrecy that began with the Smyth Report by bolstering public knowledge through seminars and research journals.

“It’s about accountability,” said Mian. “[We believe] everybody needs to know about how nuclear weapons work [and should] have a right to decide.”

Meanwhile, Morimoto facilitates Nuclear Princeton, a Native American and undergraduate-led project started in 2020, and teaches an affiliated course by the same name. According to the project’s mission statement, Nuclear Princeton works to “[focus] attention on Princeton’s involvement in nuclear projects and explore the ways underrepresented, particularly Indigenous, communities have been impacted by [science, technology, and engineering] projects.”

One major accomplishment of the project, Morimoto explained, is its online archival work that has taken strides to make science history more accessible and promote “long-term thinking about [its] impacts.”

As part of Morimoto’s Nuclear Princeton course, for instance, he takes students to the Mudd Manuscript Library to look at declassified documents from 1945. But he says one of the most interesting relics there is an irradiated roof tile from Hiroshima University. The tile was gifted to Princeton in 2012 as a thank-you and historic memento, after the University donated “one book and just enough money to plant one tree on [Hiroshima’s] campus” in 1951.

“Hiroshima basically said, ‘Oh, please use this material to disseminate the idea of peace to your students,’” Morimoto explained. “The problem has been that it’s just been kept in the archive [and] hasn’t been utilized in a way that the Hiroshima group asked for.”

Nevertheless, Morimoto recognized that Princeton actively employs faculty members like him who are teaching students about the history and environmental impacts of nuclear weapons.

Mian shared a similar sentiment, noting that Princeton physicists were both involved in making the weapon and actively campaigning against them.

“There are a lot of interesting contradictions that coexist in this [story],” said Morimoto.

Gia Musselwhite is an assistant Features editor for the ‘Prince’.

Please direct any corrections requests to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.