More than 10 years ago, history professor William Chester Jordan GS ’73 was walking with a group of students in front of Nassau Hall. As the group approached FitzRandolph Gate, instead of walking straight through the center, the students split and filed out the two side gates, as students tend to do.

Amused, Jordan asked them about the peculiar behavior. The students told Jordan the common legend on campus: that if students walked through the main gate before they graduated, they would never leave.

It was then that Christopher Eisgruber ’83, then the University’s provost, walked up. Overhearing the exchange, Eisgruber scoffed at the superstition. When he had gone to school here, there was the same superstition, he explained, and he walked in and out of the main gate all the time as a student.

As Eisgruber walked away, one of the students turned to Jordan and made the fitting observation. “And he never left,” she said.

Former University president Shirley Tilghman and Eisgruber, at the reviewing stand at the end of the 2013 P-Rade.

“Presidents” by Joe Shlabotnik / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The story captures many of the essential aspects of Eisgruber. He is the first undergraduate alum to lead the University since Robert Goheen ’40 left office in 1972. And yet Eisgruber, highly regarded by many of his colleagues, often struggles to connect with the students who attend the University he’s dedicated his life to.

Last week marked the 10-year anniversary of the University Board of Trustees unanimously approving the search committee’s recommendation of Eisgruber as University president.

The Daily Princetonian conducted interviews with Eisgruber’s colleagues, current students, University administrators, and former coworkers, and reviewed hundreds of letters, speeches, and articles by and about Eisgruber. This analysis reveals a tenure characterized by a commitment to expand access to the University at a scale that, if successful, would rank him among Princeton’s most notable presidents. Eisgruber has a substantial track record of success thus far, including expanding the student body, reintroducing a transfer program, and increasing financial aid.

The ‘Prince’ analysis also reveals a reserved relationship with community members and, specifically, a poor connection to student activists, leading to the impression of an administration intent on incremental rather than dynamic change.

Eisgruber declined multiple requests for an interview or to answer written questions for this profile.

Selection as President

“PRESIDENT EISGRUBER: Provost named next U. president” blared the ‘Prince’ on April 22, 2013. Eisgruber was hardly a surprising choice. According to a 2012 article by the ‘Prince,’ former dean of the School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA) Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 was a close contender for the role of University president, but many expected Eisgruber, right-hand man to outgoing President Shirley Tilghman, to take the role.

Professors interviewed in an earlier ‘Prince’ article said that Slaughter’s national fame, political connections, and her time at the helm of SPIA offered her distinct advantages.

However, some professors said that ultimately the decision would come down to what the Trustees thought of Tilghman’s tenure.

“If they viewed Tilghman’s tenure as successful, the committee would most likely choose an ‘in-house’ candidate like Eisgruber from within the University to continue down the course Tilghman had set,” the ‘Prince’ reported.

Eisgruber said he had never considered himself a candidate for president. He had told the ‘Prince’ in 2012, “I have always assumed that I would return to my teaching and research — which I love — after my time as provost is done.”

At the press conference announcing him as president, Eisgruber said he eventually changed his mind after reflecting and realizing that “this was a very important time for the University.”

“This was also a very important time in higher education, and one where ideals that I care deeply about are going to be affected in very significant ways,” he said.

A history of succeeding

“There are all sorts of politicians who have colorful personal lives. I don’t.”

That’s Eisgruber, describing himself in an interview with the ‘Prince’ one year into his presidency.

Over the next few years, many would try to dig into Eisgruber’s background, but stories about Eisgruber often focus more on his achievements than his personality.

The child of two German immigrants, Eisgruber was born in Indiana and moved to Oregon at age 12 when his parents took positions at Oregon State University. Eisgruber was known in his youth for his intelligence and commitment to both his schoolwork and extracurricular pursuits.

For example, Eisgruber led his high school competitive chess team to the national championship in 1979, his senior year. According to an interview his childhood friend gave to the ‘Prince’ in 2014, Eisgruber’s team cleaned parking lots and parked cars to raise funds for the trip to the championship. They ultimately went — and won.

At Princeton, Eisgruber concentrated in physics, but took many politics classes and was interested in philosophy. Jeffery Tulis, a politics professor who taught Eisgruber at Princeton, told the ‘Prince’ in 2014 that he “never had an undergraduate student even come close to the talent he showed.”

Eisgruber graduated at the top of his class before earning a masters as a Rhodes Scholar and later a Juris Doctor (JD) from the University of Chicago Law School, where he was editor-in-chief of the Law Review.

Reading the then-27 year old’s resume, Judge Patrick Higginbotham, who Eisgruber clerked for, said his first thought was: “This guy’s either brilliant or a fraud.” Eisgruber would also clerk for Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

In 2014, his college roommate, Hyam Kramer ’83, told the ‘Prince’ that “It’s hard for me to see anything ill about him, because really there was nothing ill with him.”

In an interview the same year, New York University President John Sexton, who gave Eisgruber his first job as a law professor in 1990, characterized Eisgruber as a uniquely flawless character.

“He’s a rebuke to all of us who suffer from original sin,” he said.

When questioned about times he has struggled in life Eisgruber inevitably cites a single C that he received in physics in his first year at Princeton.

Eisgruber’s seemingly invulnerable personality may contribute to the appearance of distance from the student body. Teddy Schleifer ’14, who covered Eisgruber for the ‘Prince’ extensively as he stepped into the presidency, told the ‘Prince’ that he felt Eisgruber was “not totally aware of just how big of a public figure he was about to become” when he became University president, which led to a rift between him and the student body.

Yet those closer to Eisgruber speak about his more human side. In a statement to the ‘Prince,’ politics professor Melissa Lane wrote that she was particularly affected by Eisgruber’s address at Opening Exercises in 2021, in which he spoke about his experience being diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma, a benign tumor that grows deep inside the ear.

“I was profoundly moved by his honesty about the acoustic neuroma that he has, and the lesson he shared with the entering class about the importance of remembering that ‘everyone has vulnerabilities, pain, and struggles that they conceal from the world. That is true no matter how impressive, authoritative, or composed someone may appear,’” Lane wrote to the ‘Prince.’

Stanley Katz of the School of Public and International Affairs, who has known Eisgruber since Eisgruber was hired as a faculty member in 2001, and worked closely with Eisgruber in the program of Law and Public Affairs (LAPA), shared that Eisgruber is an “an extraordinarily thoughtful person.”

He emphasized Eisgruber’s unique ability to connect with students he teaches, sharing that “almost all the students I’ve known who’ve taken something with him, but particularly his freshman seminar, have had good experiences.”

Time as provost

Eisgruber’s tenure as provost gave an indication of how he would be as president. Former University President Tilghman told the ‘Prince’ in 2014 that she did not have as defined an agenda as Eisgruber’s so early in her tenure. She said that Eisgruber’s term as provost prior to his taking on the presidency prepared him for the role. Eisgruber, who told the Princeton Alumni Weekly (PAW) recently that he didn’t initially want the provost position, served in the role for nine years.

“President Eisgruber knew the University and the way it functions and is administered extraordinarily well, because of his nine years as provost. That was a huge advantage,” Tilghman said in a recent interview with the ‘Prince.’

Tilghman described Eisgruber as the “finest provost Princeton’s ever had.”

“I was just enormously impressed with his judgment, his intelligence, his good nature,” she continued.

She specifically highlighted Eisgruber’s leadership during the 2008 recession, given that the provost is the chief budget officer of the University.

Tilghman told the ‘Prince’ that Eisgruber was able to absorb the “decline in the endowment, and do so without harming the University and that was an enormous undertaking, and he executed it, I think, really brilliantly.”

His previous administrative experience also led Eisgruber to enjoy significant faculty support at the beginning of his term.

“The University has been doing very well for a long period of time in large part because of his work with President Tilghman as provost,” then-politics department chair Nolan McCarty told the ‘Prince’ in 2014.

“I don’t expect that things will change very much,” McCarty predicted at the time.

Eisgruber’s inspiration

Despite Eisgruber’s initial claims that he was uninterested in higher roles at the University, University administration and Princeton’s history are topics he seems deeply invested in.

In a recent interview with the ‘Prince,’ former Dean of the College Nancy Malkiel said she learned that former University President William G. Bowen’s book “Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education” was a significant influence on Eisgruber. Malkiel is currently writing a biography of Bowen, who served as president from 1972 to 1988.

“The argument of that book is that admission officers should put what President Bowen called ‘a thumb on the scale’ in favor of the admission of low-income students,” Malkiel said.

Increasing access to the University has become a cornerstone of Eisgruber’s approach. Eisgruber often cites the anecdote that Princeton could admit up to 18,000 students without reducing the quality of the incoming class.

Malkiel added that Bowen’s book is “very data driven, it has extraordinary analytic underpinnings,” perhaps fitting with the technocratic approach that many ascribe to Eisgruber.

Eisgruber also took some inspiration from Princeton’s most famous, and now most controversial, president, Woodrow Wilson. In 2014, Eisgruber cited his aim to incorporate more of Wilson’s oft-cited motto “in the nation’s service” into University culture, with a desire to expand Princeton’s impact.

At his first Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) meeting, Eisgruber cited two ambitious goals, both of which would serve to expand access to Princeton: possibly reversing the University’s policy on not admitting transfer students, and expanding the student body.

Tilghman told the ‘Prince’ in a recent interview that Eisgruber was a “very careful decision-maker.”

“I never saw him make an off-the-cuff decision where he hadn’t really thought it through carefully,” she said.

Eisgruber would take years to fully implement his ambitions, but he was working at them from very early on.

The decision on grade deflation

The first major debate that Eisgruber waded into was over a policy of his predecessor’s. Grade deflation, which stipulated that no more than 35 percent of undergraduate grades given in a department should fall within the A-range, was implemented in 2004. Spearheaded by Tilghman and Malkiel, the policy was intended to combat an excess of As at Princeton.

In his first couple months as president, students pressed Eisgruber over his stance on grade deflation, a policy widely unpopular with the student body. As always, Eisgruber started first with caution. In his first interview with the ‘Prince’ as president, Eisgruber shared his support for the status quo on grade deflation, calling it a “grading fairness policy.”

By October of his first year, Eisgruber was willing to reevaluate the policy. Citing worry over the impact on prospective students’ perceptions of the school, Eisgruber charged an ad hoc committee of nine faculty members with the task of reevaluating grade deflation.

The ‘Prince’ reported at the time that, for Eisgruber, the “complaints from the student body regarding the grading policy have always been taken seriously, but that up until this point, these simply have not matched with the data the administration has gathered.”

Clarence Rowley ’95, professor of mechanical engineering, chaired the committee and told the ‘Prince’ in a recent interview that Eisgruber was “very interested in data.”

The final report from the committee included information on historical trends of grades, variation of grades across departments, impact of grade deflation on graduate school admission, and student perception of the policy.

Rowley noted that student input was “important,” and the report cited anxiety students experienced due to the “culture of competition” that the grade deflation policy caused.

Eisgruber said at the time that conversations with alumni were especially persuasive, as they, unlike enrolled students, had no personal stake in the issue.

In 2014, faculty members voted to reverse grade deflation, allowing each department to determine its own grading policy. It was a significant moment for Eisgruber’s early tenure.

Nearly nine years after this first major success of the Eisgruber administration, there are administrative concerns that the balance of grades has swung too far in the opposite direction. At a November 2021 Undergraduate Student Government meeting, Dean of the College Jill Dolan told students “the steep increase in [amount of] ‘A’ grades” is concerning. Dolan pointed to data showing that there has been a .172 point increase in average GPA since 2015.

At the Black Justice League protest

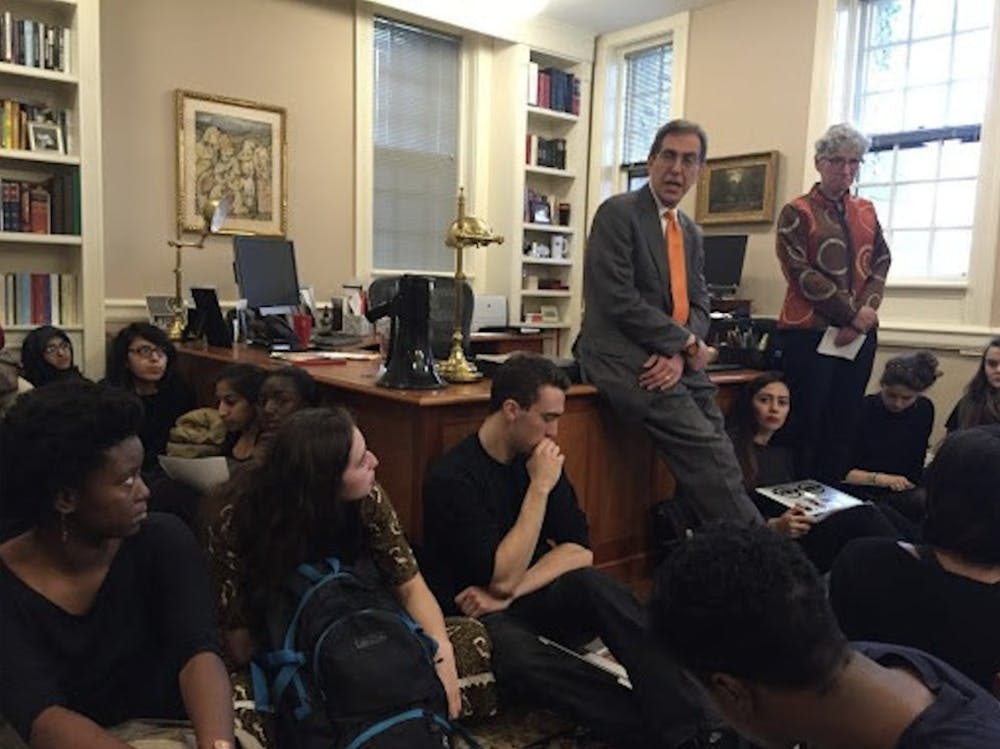

One of the most definitive pictures of Eisgruber is him sitting at his desk, surrounded by protestors from the Black Justice League (BJL) during the 33-hour sit-in in his office.

Students in President Eisgruber’s office on Nov. 18, 2015.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog, 2015

As protestors discussed their demands, Eisgruber noted the limits of his own authority, and Dolan noted that change happens “little by little.” The argument of incrementalism was not one that appealed to the protestors.

The BJL, a student organization founded in 2014 — in the wake of the police murder of Michael Brown — and dedicated to fighting anti-Black racism, told the ‘Prince’ in 2020 that they only managed to get meetings with the University administration after organizing public demonstrations.

In December 2014, the group confronted Eisgruber at a faculty panel titled “What Kind of Diversity: Is Princeton Too Narrowly Focused on Race and Ethnicity Rather Than Economic Diversity?” BJL members particularly took issue with a comment made by Russell Nieli GS ’79, then a senior preceptor in the James Madison Program.

“The racial diversity we have in this country is bad diversity and let me explain why,” Nieli had said.

After the encounter with Eisgruber, BJL members were invited to a number of meetings with University administrators.

“At that point, they were very much trying to placate,” Joanna Anyanwu GS ’15, a former BJL member, told the ‘Prince’ in 2020.

Destiny Crockett ’17, another former member of BJL, told the ‘Prince’ in 2020 that the group “got the run-around” in the meetings.

“We would meet with one person, and then they would say, ‘Oh, you should meet with this other person,’” she said.

In November 2015, the BJL held their organized sit-in, presenting Eisgruber with a list of demands, including mandated cultural competency training for faculty and staff, an ethnicity and diversity distribution requirement, and the removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from the then-named Wilson School and College. The protesters occupied Nassau Hall, saying they would stay there until their demands were agreed to.

“We are tired of talking to people. It’s conversation, conversation, conversation. We try and protest; we meet with the administration every other week,” one BJL organizer, Asanni York ’17, said at the time. “We’re done talking. We’re going to be here until he signs this paper. We’re going to be here until things are met.”

Ultimately, Eisgruber agreed to a list of revised demands, including a promise to consider a distribution requirement, affinity housing, and Wilson’s legacy on campus, 33 hours after the Nassau Hall sit-in began.

“We appreciate the willingness of the students to work with us to find a way forward for them, for us and for our community,” Eisgruber said following the sit-in. “We were able to assure them that their concerns would be raised and considered through appropriate processes.”

Since the sit-in, some of the protesters’ initial demands have been met, including the institution of the Culture and Difference distribution requirement and, notably, the removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from the School of Public and International Affairs after the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

Eisgruber had emphasized the importance of diversifying a historically white institution prior to the sit-in. At one of his 2013 CPUC meetings, Eisgruber highlighted the need to increase faculty diversity after the Ad Hoc Committee on Diversity showed that the University remains predominantly white.

In October 2021, the University released its first annual Diversity Equity Inclusion (DEI) report to track improvements in such matters. The reports have shown some improvement in faculty diversity, though the faculty remains primarily white.

Yet the 2015 sit-in captured many student frustrations with the speed of change and the administration’s communication with the student body.

Expansion gets underway

Meanwhile, Eisgruber’s earlier ambitions of student body expansion continued to unfold. In an early conversation with alumni, Eisgruber noted that Princeton was turning down a large number of students who could “greatly benefit” from the Princeton experience and could increase the potential to “make a difference in society.”

Expanding the student body was a hefty task for the one of the smallest Ivy League schools clustered around a historic campus. Eisgruber approached the task step by step.

In 2016, the University announced its strategic planning framework, which included plans to increase the number of undergraduates by 500 — 125 per class for four years — and reintroduce the transfer program for the first time since 1990.

The transfer program was reinstated in 2018 with a focus on attracting students of diverse backgrounds, including military veterans and low-income students who have already begun their college careers in community colleges.

Eisgruber had even more ambitious initiatives planned — in his 2019 annual letter to the University, Eisgruber detailed the eight-year construction plan that would allow for the expansion of the student body. This construction plan included the now-named Yeh College and New College West and the construction of Hobson College. Through the letter, Eisgruber inaugurated a new era of construction on campus.

Stanley Katz, the longtime SPIA lecturer, said in an interview with the ‘Prince’ that members of the Princeton community are not asking enough questions about this increase in the student body.

While completely in favor of the diversification goals emphasized in expansion, Stanley Katz argues that increasing class sizes is not the way to achieve such goals and only serves to make campus “less intimate.”

“If it were up to me I would cut out all legacies … and take fewer athletes,” Stanley Katz said.

Nevertheless, of Eisguber’s oft-cited 18,000 eligible applicants, more will get the chance to attend Princeton than ever before in 2024.

The Joshua Katz affair and Eisgruber’s reputation

On May 10, 2022, President Eisgruber made a recommendation to the Board of Trustees that would significantly impact his public profile.

A years-long controversy surrounding classics professor Joshua Katz was about to reach a new national audience. Two years earlier, Katz had received a year-long suspension in relation to a relationship with a student in the mid-2000s that violated University policy. The suspension had not been publicly reported at the time. In February 2021, a ‘Prince’ investigation included information about the suspension, and told the story of that relationship, along with two other separate allegations of inappropriate conduct.

Katz admitted to the first relationship but denied any inappropriate conduct with other students in a later statement.

After the alumna with whom Katz had engaged in a relationship during the time that she was a student came forward to the University, administrators began a new investigation into the professor’s conduct. Dean of the Faculty Gene Jarrett ultimately recommended that Katz be fired. Eisgruber affirmed that recommendation to the Board, which fired Katz on May 23, 2022.

According to the ‘Prince,’ Eisgruber’s letter recommending Katz’s dismissal alleged that Katz misled investigators during the 2018 investigation. Katz and his lawyers denied this claim at the time.

Katz’s own narrative surrounding the firing gained significant traction: that he was fired as part of a politically motivated effort to remove him because of an op-ed that he wrote in 2020, in which he criticized a faculty letter proposing anti-racism measures and characterized the BJL as a “small local terrorist organization.”

When Katz had written the original 2020 piece, Eisgruber criticized Katz’s statements while also saying that there would be no official disciplinary action. “By ignoring the critical distinction between lawful protest and unlawful violence, Dr. Katz has unfairly disparaged members of the Black Justice League, students who protested and spoke about controversial topics but neither threatened nor committed any violent acts,” Eisgruber wrote. Yet, Eisgruber said in a 2020 op-ed for the ‘Prince,’ that University policies “protect Katz’s freedom to say what he did, just as they protected the Black Justice League’s.”

Professor Robert P. George, the most prominent conservative scholar at Princeton, praised Eisgruber at the time of that statement, saying that choosing to publicly condemn but not investigate or dismiss Katz was fully in line with the culture of academic freedom that Eisgruber touts.

Yet after Katz’s firing, Edward Yingling ’70 and Stuart Taylor ’70, co-founders of Princetonians for Free Speech, criticized the dismissal, citing Eisgruber’s criticism of Katz’s op-ed as evidence of bias.

George, whom Eisgruber has spoken highly of, tried to thread a needle, arguing that the issue was not one of free speech but one of due process, and instead laying responsibility for the firing on others on campus, including the ‘Prince.’ But with the issue of Katz’s firing becoming a cause célèbre in conservative circles at the time, Eisgruber’s public reputation on free speech issues has been increasingly criticized from the right.

Yingling and Taylor, for instance, said that Eisgruber had “caved to the pressure from the mob” in firing Katz. They referenced other administration decisions regarding Katz as “destroy[ing] Princeton’s acclaimed free speech rule.”

Throughout his time as president, Eisgruber has expressed the importance of freedom of speech many times. He has written frequently on questions of free speech and discussed them in campus addresses. He has at times been criticized from the left for his decision not to punish offensive speech, including in 2020 by the ‘Prince’ Editorial Board when Eisgruber initially declined to punish Katz.

Even if it did not alter his convictions, the Katz affair did change the public perception of Eisgruber on the issue of free speech, as evidenced by letters to Princeton Alumni Weekly (PAW) in which many alumni criticized Eisgruber’s handling of the issue, connecting it to questions of free speech.

Eisgruber has yet to speak publicly at length on the issue. Earlier this month, he discussed the firing briefly in an interview with PAW: “I think we made the right decisions and I think I need to leave it at that,” he said.

A series of changes during COVID-19

“The last ten days have been unlike any other we have known,” Eisgruber wrote on March 17, 2020, in a letter to the community. Princeton students had just been sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, marking the most momentous world event in Eisgruber’s tenure.

The University’s pandemic response succeeded in keeping case counts on campus extremely low for a year and a half, even after some students returned to campus for the Spring 2021 semester. The University was also praised for significant engagement with the town during the pandemic.

Eisgruber’s leadership in particular was praised by department heads.

Alan Patten, current Chair of the Department of Politics, wrote in a recent statement to the ‘Prince’ that, “Eisgruber was a thoughtful and prudent leader in the time of the pandemic, who kept his eye on the big-picture goals and values of the University.”

Yet Eisgruber’s role on pandemic issues from a student perspective was notably low-profile. Eisgruber wrote infrequently on the pandemic itself, and major University announcements were often signed by Vice President for Campus Life Rochelle Calhoun.

Eisgruber has taken a more public role at other moments during his tenure. For example, in 2019, Eisgruber stood on the steps of the Supreme Court in support of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, next to María Perales Sánchez ’18, a DACA recipient, and Brad Smith ’81, president of Microsoft. The University successfully sued the government after former President Donald Trump threatened to revoke the order.

In contrast, Eisgruber’s tenure during the pandemic was marked less by public-facing gestures and more by the culmination of many of Eisgruber’s long-sought plans.

As students studied at home, construction was proceeding on two new residential colleges and plans were being reviewed to build a third.

This fall, the Class of 2026 walked through FitzRandolph Gate as the largest class in the University’s history, sitting at 1,500 first-years.

A slew of University policy changes in the aftermath of the pandemic also shows an administration with continued ambitious goals to remake the University. In 2022, the University renamed concentrations to majors. This change overturns more than one hundred of years of Princeton history: the concentration was established by Woodrow Wilson himself.

Also in 2022, after years of activism, the Board of Trustees voted to divest from all publicly-funded fossil fuel companies. The move was a major milestone for the University, yet what activists remember of Eisgruber’s role was his unwillingness to engage with them at the time.

Hannah Reynolds ’22, an organizer with Divest Princeton, told the ‘Prince’ that the group “repeatedly asked President Eisgruber to meet and he repeatedly maintained that he had no influence over the decision [to divest] and that he was unwilling to meet with students who ‘had an agenda.’”

Reynolds feels Eisgruber’s response was “misleading” as Divest observed “he plays an influential role in Board of Trustee decisions.”

In an interview with the ‘Prince’ last Fall, Eisgruber praised Princeton’s process around the divestment decision, saying that it emphasized reaching a “community judgment,” rather than having an unexplained announcement come from University administrators.

“If we were to do something in response to a particular group on campus without it reflecting the deliberations of the entire community, including those who disagree with that group, then we would be unfaithful to this process,” he said. “There’s no doubt that the activists played a significant and important role in contributing to these conversations.”

The pandemic era also saw the start of construction on a massive new engineering complex, which Eisgruber has highlighted as a recent goal. Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, Andrea J. Goldsmith, shared in an email with the ‘Prince’ that a major part of her decision to join Princeton in 2021 was excitement over “the bold strategic plan that President Eisgruber crafted early in his tenure.”

Goldsmith said that Eisgruber’s “historic investment in the engineering school” will “catalyze collaborations … launching interdisciplinary research.” She is confident that “under President Eisgruber’s leadership, Princeton and its School of Engineering are poised to play a critical role in mitigating the threats and seizing the opportunities facing our country and our world in the decades ahead.”

Engagement with the student body

Eisgruber’s tenure will continue, after the Board of Trustees voted in April 2022 to extend his term by five years, specifically citing his expansion of the student body and his stalwart defense of free speech. Eisgruber’s effort to remake the campus has not stopped — construction projects are all across campus, and large swathes of Princeton in 20 years will be Eisgruber’s legacy. With expanded financial aid for the coming year, the socioeconomic diversity of Princeton’s class may increase as well.

Yet Eisgruber continues to face criticism from the University community for what some describe as a closed-off style of leadership and a lack of engagement with the student body.

Schleifer, the former ‘Prince’ reporter, says that he believes Eisgruber should engage with the student body like a politician would, like a “constituency that he needs to cater to,” adding that Tilghman had a “normal relationship” with students and was open to interviews with them.

Stanley Katz, the SPIA lecturer, says he feels President Eisgruber is “notably isolated.”

“I think it’s a mistake … it’s his job … but I think he can be more effective if he could manage to spend more time with more people,” Stanley Katz added.

Stanley Katz blames Eisgruber’s bureaucratic approach for the lackluster connection between students and the presidency, saying “there are simply more folks between [President Eisgruber] and you.”

In another interview with the ‘Prince,’ John Raulston Graham ’24 noted that Eisgruber does not often share his experiences as an undergraduate at the University.

“He’s an alumnus, just like many other past Princeton presidents, and I’m sure he has tons of experiences at Princeton that could endear him to students,” Graham said, adding that “it’s sad to me that I don’t hear about those.”

“I would love to hear what it was like for Eisgruber to go to events for students at Princeton that we still have, because there’s so much continuity,” he said. Graham added that he would also like to see Eisgruber at more athletic and student performance events.

Eisgruber does hold informal conversations with students, speaking at the different residential colleges with undergraduate students, and at the Lakeside commons for discussions with graduate students. This semester, Eisgruber also held scheduled office hours on April 5. Students could sign up online and were required to provide topics of discussion in advance.

Eisgruber was also criticized last fall for comments about student mental health which some saw as reflecting a disconnect with the student body.

In a rare discussion with the ‘Prince’ in November, the ‘Prince’ asked Eisgruber about the University’s role in preventing mental health crises, and whether he saw “there being a tension between the rigor and productivity demanded of Princeton students and student mental health.” The issue was being widely discussed on campus at the time, as the interview happened a month after the fourth student death by suicide in two years. Eisgruber first pointed to the “mental health epidemic in the country,” then addressed the more specific query.

“I think high aspiration environments, and that includes academically rigorous environments, are fully consistent with and helpful to mental health. I think part of what creates meaning and connection in our lives is engagement and demanding collective enterprises,” he said.

“I don’t see any evidence that academic laxness or academic mediocrity would somehow be better from the standpoint of mental health,” he concluded.

Eisgruber faced stiff criticism from students following the publication of the Q&A.

In a guest contribution published in the ‘Prince’ a month later, Eisgruber cited multiple studies about the causes of the mental health crisis, but students have continued to criticize his inability to connect with the subjective reality on campus. “Structurally, it does not seem like my voice as a student is being heard,” Jupiter Ding ’24 told the ‘Prince’ regarding Eisgruber’s comments and subsequent response.

Eisgruber, however, tends to use other avenues to share his thoughts. In recent years, the President’s Page in PAW has become his place to weigh in on major campus debates — writing discursive essays to a primarily alumni audience on issues such as institutional restraint and campus events such as commencement.

In his interview with the ‘Prince’ last fall, Eisgruber spoke more about the obligation he sees for a Princetonian, such as himself.

“All of us are blessed to have a place on this campus — and I have felt blessed in my life to have been a student and a faculty member here. That gives you opportunities that are rare in the world,” he said.

He continued: “And I think your obligation as somebody who has experienced those rare blessings is to ask ‘How do I pay it forward? How do I make a difference in the world for the better with what I’ve done?’”

Sandeep Mangat is a head News editor for the ‘Prince.’

Bridget O’Neill is an assistant News editor for the ‘Prince.’

Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.

Correction: A previous version of this piece inaccurately named William Bowen as an undergraduate alumnus; he was a Graduate School alumnus. A previous version also inaccurately characterized the specifics of the incident Yingling and Taylor were referring to regarding Princeton’s free speech rule. The ‘Prince’ regrets these errors.