Ellen Bernstein ’73, a psychology major, was a member of the first class of women admitted to Princeton in 1969. Though she had initially been interested in “more progressive [schools] ... Brandeis, Swarthmore, and some of the women’s colleges on the East Coast,” when she found out that Princeton was implementing coeducation, she sent in an application and was later accepted with some financial support.

“There wasn’t any question I was going to say yes,” she said in an interview with The Daily Princetonian.

Bernstein, from a “mediocre, working class, public high school,” was the only person from her school to attend Princeton that year. There was one alumnus from her high school at Princeton, and he invited her to reunions the year she was admitted. They wore buttons with their names and class years.

“It was like being dropped out of a spaceship onto an alien planet,” she said.

Bernstein remembered seeing a “little old man” wearing a striped jacket with tigers and a hat.

“He came up to me and looked at my buttons and he said ‘1873, your dad's awfully old, isn't it?’,” she said. “I said ‘no, sir. I'm coming here next year as a freshman.’ He said ‘you were one of those coeds,’ and he started to cry.”

“Coeducation was changing his old Princeton,” she added.

Bernstein and four other women from the Class of 1973 spoke with the ‘Prince’ about being a part of the first four-year class of women at the University and their experiences as students, which they described as generally positive. Victoria Bjorklund ’73, who joined the University a year later and graduated in three years due to advanced standing, also shared her experiences.

Princeton University became coeducational in the fall of 1969. Transfer students started to graduate as early as 1970, though the Class of 1973 was the first class to spend all four years at the University.

In 1967, President Robert Goheen ’40 led a study on the possibility of admitting women as full-time undergraduates. In a conversation with student reporter Robert Durkee ’69, Goheen said that “it is inevitable that, at some point in the future, Princeton is going to move into the education of women.” Additionally, he emphasized that the primary reason for adopting coeducation would be “what women could bring to the intellectual and entire life of Princeton.”

There was opposition, however. Founded in 1972, the Concerned Alumni of Princeton (CAP), which counted Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito ’72 among its membership, came out against coeducation. They believed that the administration lacked “an understanding of and respect for what it has meant to be a Princeton scholar and a Princeton gentleman.”

In 1969, 102 female first-years and 48 female transfer students enrolled. It took until 2004 for female enrollment to reach 50 percent despite admissions becoming gender-blind in 1974.

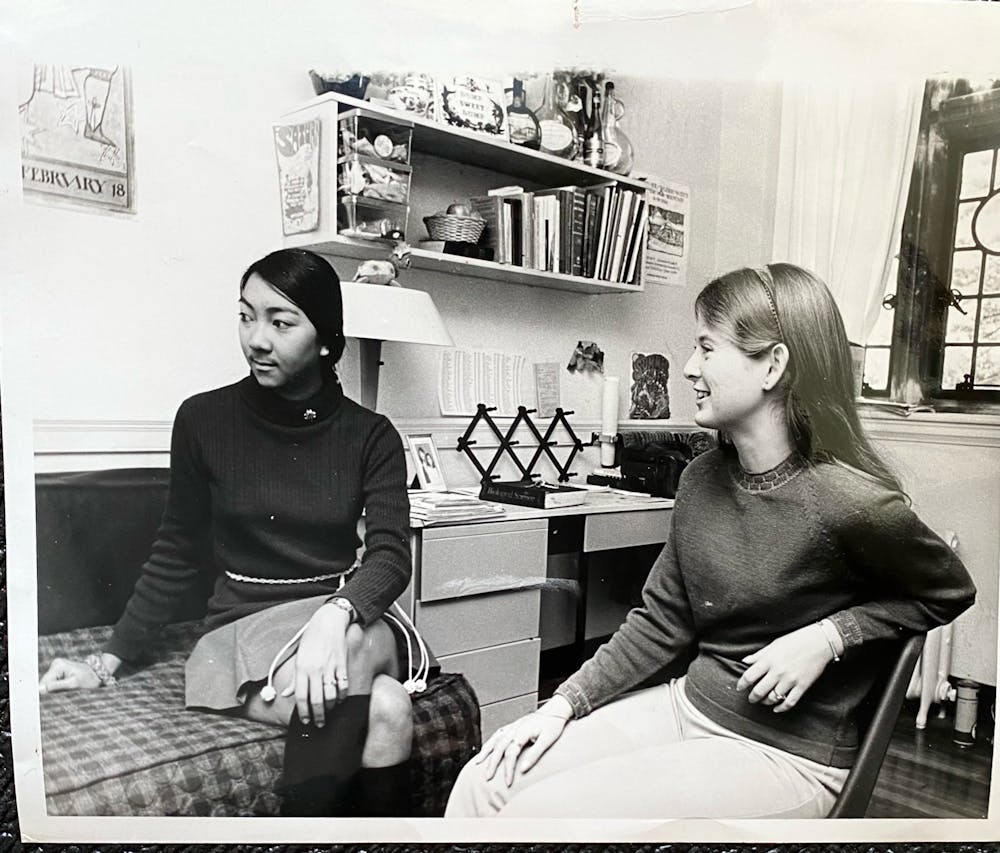

Elaine Chan ’73, a biology major, was from a family of “modest means,” in her words, but when she got accepted to Princeton, she remembers her father saying, “It doesn’t matter how much it costs. You will go to Princeton.”

Susan Belman ’73, an English major, reflected on women coming to campus, and said that she and others were “busy trying to assimilate ... trying to get their foothold in the overall Princeton community.”

“One of the things that struck me when I got to Princeton was how almost everyone I met was so happy to be a student … there was a feeling of gratitude,” Belman said. “The fact that there were so few women at the time, for me, I think that made it that much more special. I felt as though I was part of the chosen few.”

All undergraduate women in the Class of ’73 lived in Pyne Hall as first-years. Bernstein remembered that this didn’t necessarily make a coherent community, as Pyne Hall is split into entryways that don’t connect indoors.

While shared residential spaces offered some proximity, several alumni noted that seeing so few women in the classroom often felt isolating.

“Most of us were the only woman or the one of the only one or two women in our small classes,” Bernstein explained.

“I never had a woman professor and I was rarely ever in a class with another woman,“ added Victoria Bjorklund ’73, a medieval studies major.

Joanna Cayford ’73, also a medieval studies major, was the only woman in her 100-person history class. “That was the only class I think I really noticed that I was the only woman,” she said. “The other ones, not so much.”

Nevertheless, the alumni shared that they derived a lot of value from being in the classroom.

“I think that bringing a woman’s perspective into some of the discussions really enriched [them],” Chan remarked.

Cayford described her professors as “entirely welcoming” and the Princeton experience as “one of the best things [she] ever did.”

Cayford also described her social circle as primarily men throughout her time at the University.

“I had always hung out with guys. I had brothers to play cards with and the guys in my high school and all this kind of stuff,” Cayford said. “So it was very easy for me to move into the Princeton social thing, and very quickly I was basically living up at Holder Hall.”

For some, however, elements of the transition to Princeton. were not quite so smooth.

Bjorklund is an athlete and was the captain of her basketball team throughout high school. She recalled walking over to the equipment room in Dillon Gym to play basketball.

“We don’t have any basketballs for girls,“ she was told.

She then connected with Merrily Baker, who came to Princeton the fall that Bjorklund joined the University, to help establish women’s athletics.

Baker encouraged her to walk back slowly and ask again, and once she did, they handed her a ball. Baker often watched her play. Bjorklund was never allowed to be a part of a pickup game, but the next year, she received the first call from Baker that the University was going to start a basketball team.

“I’m the oldest woman basketball alum,“ she said. She mentioned that by time the team was created, the men who initially barred her from playing basketball were later happy to see her come back day after day.

Chan, Bernstein, and Cayford didn’t join eating clubs. Many were not yet coed. Bernstein remembered going to a meal with a friend and being seated in the middle of the table. She was the only woman eating there that night.

At the time, graduate student women were joining the campus community for the first time as well. Sandy Cope GS ’73, a graduate student in chemistry, became a graduate student and teaching assistant in 1969. She monitored an organic chemistry laboratory each week, which she described as “great fun.” As a graduate student, she said that her world revolved around the chemistry department. She lived in the Graduate College, where she wore “robes to dinner” at the dining hall and met students in a variety of departments.

The alumni also noted how their intersectional identities uniquely shaped their experience at the University.

As a first-generation woman at Princeton, Bernstein said that she didn’t know how to “center [herself] in the Princeton narrative.”

“I didn’t know until my junior year how many of my classmates were millionaires or were from fancy families. And, I did also know a lot of other first-generation students, but I think I blamed all my insecurities on myself and internalized it,” she said.

At Princeton, Chan mentioned that she didn’t feel academically isolated, but did feel socially isolated as an Asian American woman from a public school. She said that the University tried really hard to bring students of color to the University and would often ask her to speak on panels. She didn’t feel “tokenized,” but rather enjoyed having a voice on the panels.

“I just feel honored that I will be able to represent and have an opinion that somebody would care about,” she said.

Chan also served as an assistant to Conrad Snowden, who was the master of the Third World Center, now the Carl A. Fields Center for Equality and Cultural Understanding, at Princeton. She was able to set up programs and intercultural events for students of color.

“We could get students out of their courses and out of the lab to come in and spend time together and just to meet students so that we wouldn't feel isolated,” she said.

Chan reflected on her growing sense of self over the course of her time at Princeton. “I learned to be confident and to not pay attention to the little things, like being a woman or being female scientists, young and Asian, where our stereotype is to be timid and retiring.”

“When you speak up, most of the male managers and people in charge are not accustomed to dealing with bold Asian women. So they wouldn’t know how to say no, so I would just take advantage of that,” she added.

When Chan’s mother passed away, she gave her inheritance to the University on one condition: that they use it “to start an Asian American studies program.” There is now a certificate in Asian American Studies.

All of the women mentioned that they do not regret their experiences and would come back to the University.

Bernstein emphasized the “great education” she received, studying in the psychology department and taking a variety of classes. She remembered a Shakespeare course in the English department, where she read a giant book of his work.

“If I could go back [to Princeton] now, I would go in a minute and I would study with [African American Studies Professor] Eddie Glaude [’97], [Sociology Professor] Matthew Desmond and [African American Studies Professor] Imani Perry. I would want to take advantage of the resources there,” Bernstein said.

Cope expressed a similar sentiment. “There’s so many things to do,” Cope said. “Get involved. It’s overwhelming.”

Belman fondly remembered walking across campus through Prospect Garden, and reflecting on the feeling that she will “never be in a place as beautiful as this.”

Although she recalled having a “wonderful life,” she mentioned that “there was a magic about [her] experience at Princeton that has not been duplicated.” She summed her experience of Princeton as “really special” and has served as an alumni interviewer for the past 30 years.

Cayford expressed a similar sentiment, that “My freshman year at Princeton was the best year of my life.”

“I remember I finished a paper at seven in the morning, and I would go to the chapel and just watch the sunlight coming in through the windows,” she said. “That was so beautiful. I really enjoyed … things like that.”

Bjorklund later served on Princeton’s Board of Trustees as an Alumni Trustee, where she worked to make Princeton “a great place to go to school for everybody,” and hoped to increase diversity and resources for first-generation, low-income (FGLI) students.

She recalled attending her 40th reunion, where she was introduced to a woman who was hired by Princeton from Radcliffe to review women in the Class of ’73’s applications. The woman explained that among the things, she was told to look for included women who had a backbone and women who had brothers. Bjorklund explained that she has both.

“Going through the first class of Princeton ... I wasn’t going to let anybody indicate to me that I was less than any other student,” she said.

Chan is in charge of organizing the P-Rade experience for the Class of ’73. She has attended the vast majority of Reunions experiences and is excited to return to campus soon.

“There’s a lot to learn from the way Princeton brings people together,” she said. “I'm just thrilled every time I go to Reunions and I see all these women in the parade and the younger classes. My heart leaps in my chest.”

Lia Opperman is an associate News editor for the ‘Prince.’

Louisa Gheorghita is a news contributor for the ‘Prince.’

Please send any corrections to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.

Correction: A previous version of this article improperly characterized former Sen. William Frist as a member of the CAP.