Reed Leventis ’23 began planning his senior thesis piece, an immersive theater experience called “Disorder,” last year. “Disorder” was presented at the Wallace Theater of the Lewis Center for the Arts from Feb. 17 to Feb. 25.

The Daily Princetonian sat down with Leventis, a senior in the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology department, to hear his reflections, vision, and hopes for the piece.

Responses have been edited for clarity and concision.

Daily Princetonian: What was your artistic vision behind “Disorder”?

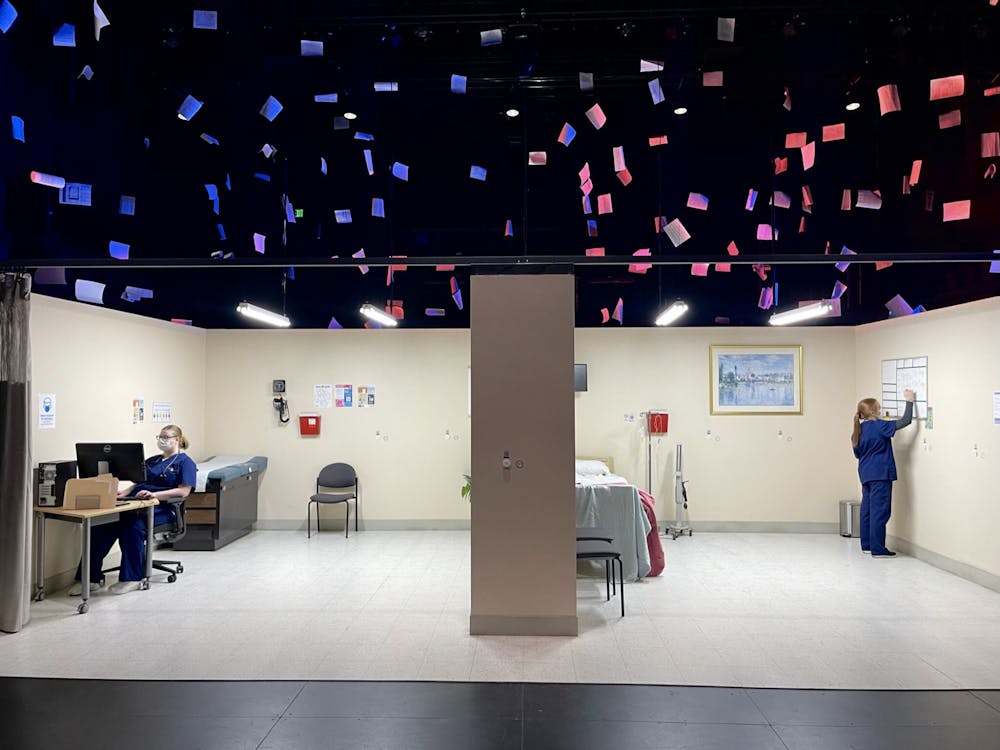

Reed Leventis: The idea that I had was to create an immersive experience that was half live performance [and] half installation about the healthcare system and how we all move through it. It was very much meant to be a community piece. I didn’t want it to be something that was just my own voice. So I always knew that I wanted to recruit a lot of people to work on it and incorporate their own stories into the experience. And so really, the vision was to have a piece that explored the edges of the healthcare system and these hidden stories that we don’t really talk about a lot in our day-to-day lives, even though it’s something that we all experience and we all move through.

DP: What motivated you to create the immersive theater experience?

RL: There are a couple of things that motivated me to do it. The first was [working] on an ambulance in a really rural place in the United States ... [and] hearing a lot of stories from individuals. And that really got me thinking about these hidden stories that we ignore, both on the healthcare provider side and on the patient side. We kind of tend to treat it as, “Oh, I went to the hospital and this happened,” rather than “What does it look like if we’re talking about the humans behind that experience?” Both from a provider side and a patient side, there are people behind these experiences, there are stories behind these experiences. And the second was [that] people started talking and were like, “that’s a really cool idea. I want to do this for that,” and people had stories to share. People had things to say and had things they wanted to share, and I was very happy and excited to be an outlet for people to share the screen, share their own stories. That was, I think, what was the most profound — people had a story to tell, and I wanted them to be able to do that.

DP: What was the most rewarding part of putting the piece together? What was the most challenging?

RL: I think the most rewarding and the most challenging was the monologues because I was working with a lot of writers with varying levels of writing experience. I think that the most challenging part was coordinating all those monologues and making sure we had voice actors for them and making sure we were doing each monologue justice in the way that the person who wrote it wanted it to be portrayed. In many ways, that was the most challenging, but also the most rewarding. And then the other rewarding part was just hearing feedback from people, from providers who came up to me afterward, like there was a doctor who came up to me and was like, “this is really, really interesting and has actually reflected a lot of what I’ve been feeling.”

DP: You mentioned that both providers and patients came up to you after the piece and expressed that it really resonated with them. How did you structure that first outreach to the larger group of people from whom you sought to hear stories such that both groups would find it resonant?

RL: I think we didn’t get as many provider voices in there as I wanted. A lot of it was sourced mainly from Princeton students. So while I did have providers talking with me, my advisor was a doctor. And so she gave me a lot of feedback. I feel like that helped a lot [in making] its way into the process. So it felt like it was impactful for providers as well.

But I think the initial outreach process was [through] word of mouth to build that network of people. People [who contributed] had a lot of autonomy in this piece. And a lot of people who worked on it were almost taken aback by how much autonomy they had. The only structure for those monologues was “write a story about you that centers around an experience that you or someone you know had with the American healthcare system.” I think that gave people a chance to really do what they were interested in. And the same thing with the visual arts pieces; the people who contributed there had a lot of autonomy over what they wanted that to be. I really wanted people to feel like they had their voices heard and were able to do what they wanted and present what they wanted.

DP: Would you say the piece was a unifying experience in that both patients and providers found it resonant?

RL: I wanted it to feel like we are all humans existing within this space — within this thing — that at some point we receive care from. I don’t know if unifying is the right word, but I think it definitely resonated with a lot of people. And it made me really happy that people felt seen.

DP: What do you hope that those who attended took away?

RL: See, I think that’s hard for me to say because people come in with vastly different experiences. But I hope that people heard an idea or perspective that they had not considered before.

DP: What did you learn from the show?

RL: On a more artistic-producing level, I learned the complexities of trying to do a community-driven piece like this. It’s a lot of logistical stuff. And that’s tough, but it can also be very rewarding. You know, if I could do it again, I feel like I would know so much better how to go about organizing it. And I think I, too, learned a lot of different experiences that I hadn’t heard about before.

I feel like I learned a lot about accessibility in theater. Also, the lack of information sometimes on [where] to find the things I was looking for, like dimensions, [was] sometimes very difficult. The ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] would say doorways have to be 32 inches wide. But then I would look it up and [see that] there are wheelchairs that can be up to 36 inches wide. I don’t want someone to come to this and then not be able to get through that door. Some of that was like a really big learning process, and I don’t feel like I perfected it at all. But accessibility was something that was really important for me to try and learn about more through this process of what accessible immersive theater looks like. I don’t claim to say I perfected it, but it was one of my learning goals for the project.

DP: Could you elaborate on how you went about pursuing the goal that you had of making sure that this was an accessible theater experience?

RL: I’m lucky enough to have some friends that are involved very much in accessibility work. So a lot of it was reaching out to them, because they were more [of an] expert than I was. And then a lot of it was talking with my advisors, but also doing a lot of research online of what the ADA standards were. From what I see is that the ADA seems to set minimums. How do we go past the minimum and try and do better than that? So a lot of it was just talking with people I knew who were involved in disability advocacy and had been involved in accessibility. And that was, like, my starting-off point, and then also having a lot of stories from people with disabilities in the experience was something important to me. And I think that that came to fruition as well.

DP: What do you think comes next for the piece?

RL: To be honest, I didn’t think about it because I was so into just doing this [piece]. And so I’m talking with some people right now about [whether] this is something that can live on. Is there a world in which this goes somewhere else? And obviously, if it goes somewhere else, it wouldn’t be a Princeton show. If it goes somewhere else, it will be the voices of that community. So if it goes to New York, it would be people from New York writing stuff. If it goes to rural Washington State, it would be voices from rural Washington State. At the heart of it is a community piece, so you want it to feel like you’re seeing yourself reflected in the stories that are being shared and the artists that are involved. So it ends up [being] much more profound.

It’s easier to be detached from it if it’s not someone involved in your community. I’m not saying it should be that way. But I think it’s easier for audience members to detach themselves from reality if it’s not their community. Also, there’s an importance in representation and in people seeing themselves represented in the art that’s taking place in their community.

DP: Was there any particular moment where you received feedback after the piece that was particularly resonant for you?

RL: There was a doctor who came up to me, who was really impacted by it, and was like, “I would love to be involved if you ever do anything again like this.”

And I thought, “Wow, that’s really interesting that someone that’s obviously very busy felt this piece to be valuable enough to do this again. That’s interesting that people feel like it should happen again, and should happen in different places to continue this dialogue.” And so I think people’s implication of “you should do it again” was really striking.

Anika Buch is the Research Editor at the ‘Prince’ who typically covers STEM communities and on-campus research. She can be reached at ambuch@princeton.edu.