The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone. For information on how to submit an article to the Opinion Section, click here.

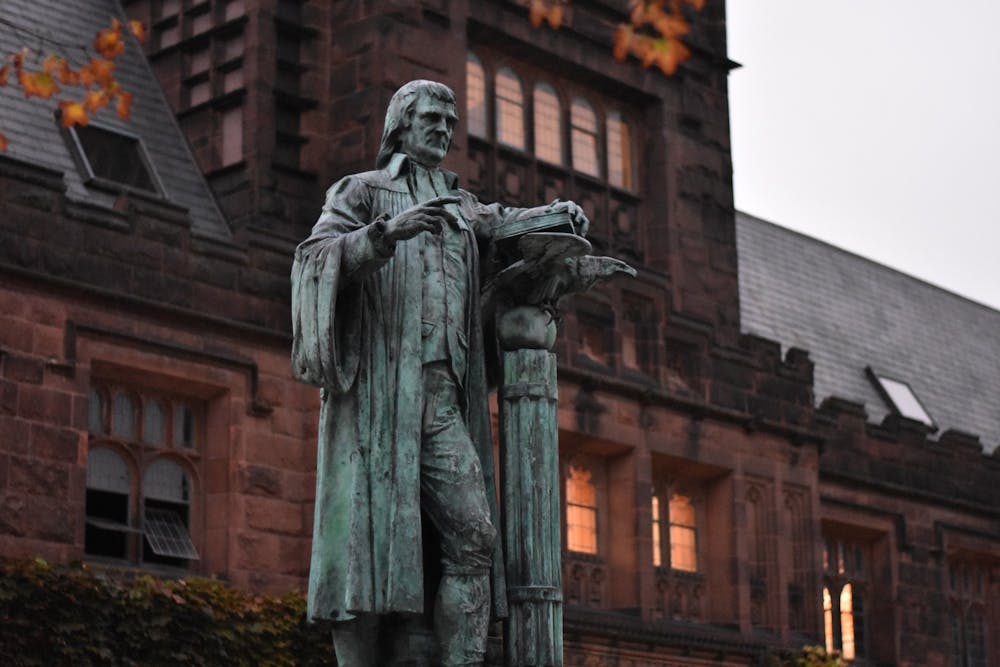

“And when these walls in dust are laid … ” shall any sing praise of Old Nassau? How should future Princetonians judge our actions? How should we ourselves now remember — even honor — our forebears? And how shall we attempt to inform and persuade one another on these and other concerns? This question lies at the heart of the debate over Princeton’s Witherspoon statue. I firmly believe that this debate must be governed by principles of free speech. Furthermore, rather than condemn and erase Witherspoon’s legacy, I maintain that we ought to remember and honor him.

“[T]ear down this place … ” to make Princeton better, remarked Professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta ’06 as part of a Class of 2025 Orientation Session in Fall 2021. (Padilla Peralta’s full statement can be viewed online, beginning at the 38:20 mark.) This quoted phrase may trouble some. But quite properly, the making of such statements is protected by the Statement on Freedom of Expression, adopted by Princeton’s Faculty in 2015 and incorporated into the University Principles of General Conduct and Regulations. These free speech principles underpin a healthy university. Princetonians should hold them fast and dear.

I join Professor Padilla Peralta and the rest of the Princeton community in the goal of making Princeton a better place. When we in this community differ, we should seek first to learn and understand better, not reflexively condemn individuals nor cut off debate.

If Professor Padilla Peralta’s use of this metaphoric — even hyperbolic — phrase were to lead us to dismiss the rest of what he said, we would lose the benefit of his thinking and advocacy. The writing of another Princeton community member, former professor Joshua Katz, then evaluating a petition then circulating in the University community, also had instances of metaphoric, even hyperbolic phrasing. These comments led to torrential controversy (unfortunate in several ways, in my view). The focus on Katz’s phrasing swept away consideration of his thinking and advocacy on important matters for Princeton.

In contrast, the recent proposal to remove the statue honoring John Witherspoon has started an open and productive debate on an issue worthy of engagement by Princetonians. I commend the petitioners for their advocacy by reason and persuasion, rather than by such means troubling to me as the seizure of a campus office or building. Their statement not only induced me to better understand what the Witherspoon statue means to them, but also led me to learn more about Witherspoon himself.

As an undergrad, well before the appearance of the statue, I was ignorant of who Witherspoon was, apart from the namesake of an old dorm and the street north of FitzRandolph Gate.

Now, I (and I believe many more Princetonians than in my campus years) know much more about Witherspoon, including some of his distinctions: a crucial early president of Princeton, teacher of political and moral philosophy to James Madison Class of 1771 (who became father of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights), and signer of the Declaration of Independence (an act of great personal risk). At Princeton, Witherspoon lectured against slavery. However, believing that slavery would soon die out in New Jersey, he did not support its immediate legislative abolition and himself owned slaves until his death.

Witherspoon’s involvement with slavery is central to the petition to remove his statue. True, there is at least one piece of precedent for the removal from Princeton of a statue meant to honor, the removal of the statue of W. Earl Dodge Class of 1879. But on the point of removing Witherspoon’s statue because of his association with slavery, I strongly disagree with the Witherspoon petitioners. Others make a more robust case for keeping the Witherspoon statue than I shall attempt here, but allow me a few observations.

The petitioners explicitly sidestep even considering Witherspoon in the context of his own times and circumstances, saying: “Regardless of our evaluation of Witherspoon’s moral standing given his time and context, the issue of the race-based enslavement of human beings presents a rupture between us and John Witherspoon.”

Arguably worse, the petitioners fail to balance the benefits and harms of Witherspoon’s thoughts and actions to others, not only in his time but also down to our time and beyond. Essentially, the petitioners’ sole criterion for removal of the statue of this slaveholder is the avoidance of “distraction” and “discomfort.”

This standard is dangerous. Should Princeton now revoke the honorary degree it conferred on Lincoln because of statements and acts of his that now cause some of us discomfort? The ancient Greeks and Romans practiced slavery; Christianity’s Apostle Paul called on slaves to obey their masters (Ephesians 6:5). Shall Whig and Clio Halls, the Chapel, and all Princeton structures with distracting associations be torn down?

We should remember Witherspoon, not erase him. His towering prominence in thought and deed makes him a valuable subject of our understanding. Through better knowledge of Witherspoon, in the words of Wayne S. Moss ’74 in Princeton Alumni Weekly, “Princeton can use its past to enlighten the present and help preserve and protect the future.”

But why honor Witherspoon? This Moses (like the one of Exodus, also flawed) did not take us to a future that resembles the promised land. But without him, Princeton might never have progressed to the point it has today. For this Witherspoon deserves our honor as a University and a nation.

Moreover, the resolution of the present dispute has importance far beyond the location of one bronze statue and the reputation of one individual. Will the resolution affirm learning, the pursuit of knowledge, intellectual independence, and freedom of speech at Princeton? Or will it follow a Siren call toward making “anti-racist social justice” (to borrow Professor Padilla Peralta’s phrase) the sole fulcrum upon which all is judged?

Princeton is not the only university to address issues from its past. Some years after its founding, the institution now known as Yale adopted the name of a benefactor who had grown wealthy promoting the slave trade. In recent years, Yale University declined to change its name, asserting “Elihu Yale was ‘relatively unexceptional in his own time’ with respect to slave trade.”

Witherspoon, in contrast, was decidedly exceptional to the norms of his time in his opposition to slavery. The petitioners to remove his statue have a tragic misunderstanding, I submit, of the full measure of Witherspoon on slavery.

Perhaps Yale will revisit its decision. Here at Princeton, the University’s response to the Witherspoon statue petition lies ahead. Similar petitions may follow.

I ask the reader to indulge my closing this piece with a dash of humor — Yale was originally (and imaginatively) named Collegiate College. Like Princeton (once named the College of New Jersey), Yale had a shaky start. Collegiate College survived owing to the labors of a deserving person largely passed over by history. Therefore, in the spirit of that titular work of Jonathan Swift, I make a modest proposal:

That members of the Princeton community provide recognition whenever practicable to Collegiate College’s essential benefactor, Jeremiah Dummer, by referring to Yale University as Dummer University.

Bill Hewitt is an alumnus of Princeton in the Class of 1974. In this exercise of free speech, Bill is prepared to be labeled a Concerned Reactionary Alum of Princeton (CRAP), preferably by Yalies. He can be reached at hewitt74@alumni.princeton.edu.