When Grant Wahl graduated from Princeton in 1996, he refused to take the easy road.

The Mission, Kan. native had received an offer to write for The Miami Herald, having impressed the editors while interning there the summer after his graduation. But the aspiring sports journalist had his eyes on a different prize: a job at Sports Illustrated.

The magazine had been his “bible” since he’d received it as a Christmas gift from his parents at age 10. In elementary school, he wrote a letter to the magazine expressing his interest in writing for them. Joining the publication over a decade after sending this letter, he’d have to start at the bottom as a fact-checker. But Wahl hoped that within two or three years, he could become a writer.

By 1997, Wahl had achieved his life-long goal, with plenty of time to spare. He started off covering college basketball and soccer, with the latter eventually becoming his primary focus. Soccer was not a tremendously popular sport in America when he first started to report, but Wahl played a crucial role in transforming it into a central feature of American sporting culture. Bringing the beautiful game to an American audience was the mantle he’d carry for the rest of his life.

Wahl died suddenly on Dec. 10 at age 49 of an ascending aortic aneurysm, while covering the World Cup in Qatar.

“I felt, feel, obliterated,” his brother Eric Wahl wrote on Twitter. “Grant was my confidante, my champion, my friend, my defender, my brother & only sibling.”

With the news of Wahl’s passing, tributes poured out from the sporting world and beyond. Former Princeton men’s soccer and U.S. men’s national team coach Bob Bradley ’80 recalled how Wahl was “fearless in his pursuit of truth.” Tennis star and activist Billie Jean King noted his ability to “elevate those whose stories needed telling.” And Wahl’s classmate Derek Kilmer ’96 (D-Wash.), honored him with a speech in his memory on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

“This has obviously been a really hard time, and to get that kind of love and support and to know how he’s going to be remembered, that really means a lot to me,” Wahl’s wife, Céline Gounder ’97, told The Daily Princetonian.

‘Among the best of his generation’

While Wahl is remembered by those close to him for his kindness, generosity, and commitment to social justice, many will know him first and foremost for the tremendous impact of his journalistic work. Chris Stone, a former editor-in-chief of Sports Illustrated who worked with Wahl at the publication for over 20 years, fondly remembered the tremendous passion with which Wahl approached his work from his very first days with the magazine.

“He pitched stories relentlessly, and he was well-regarded enough at the beginning that he would get to do some of those stories,” Stone told the ‘Prince.’ “But as time went on, his ambition and the stories he was seeking out on his own just grew.”

In 1998, Wahl had a big break at the magazine, scoring his first cover story just about 18 months after signing on as a fact-checker.

“It was a big deal,” Stone said. “It conveyed that Grant was on his way.”

In 2002, he authored the story that graced one of Sports Illustrated’s most iconic covers, which depicted the then-17-year-old LeBron James and anointed him ‘The Chosen One.’

“Grant would have had all of the success that he found at Sports Illustrated without that cover, but I’m sure he was very happy to have that story in his portfolio,” Stone said of the piece on James.

Shortly after Wahl’s death, the NBA icon took to Twitter to express his reaction to the news.

“You had a huge impact on me and my family and I’m so appreciative of you,” James wrote. “A great person and journalist. Rest In Paradise Grant Wahl.”

That cover story helped pave the way for Wahl’s legendary, multi-decade career at the publication, which included over 30 cover stories and lasted until 2020. For those who knew him at Princeton, Wahl’s rapid ascent and eventual stardom at the magazine was anything but shocking.

“Grant Wahl really was among the best of his generation,” Carlo Balestri ’96, former editor-in-chief of the ‘Prince,’ told the paper. “We all knew that he was a superstar, and no one was surprised when Sports Illustrated hired him right out of school.”

“Grant was a tremendous talent — a top-level pro among club players who were just learning to dribble when they joined the ‘Prince,’” added former ‘Prince’ editor-in-chief ABC political director Rick Klein ’98. “He was a fully formed writer as an undergrad — fluid, versatile, quick, thorough and just plain great.” (Klein is a member of the ‘Prince’ Board of Trustees.)

‘One of the premier writers to ever go through the halls of The Daily Princetonian’

Some students enter college without an idea of what they want to do, or change career paths midway through school. But Wahl recognized his passion for sports writing before he even got to Princeton. In fact, he mentioned his desire to write for the ‘Prince’ Sports section on his application to the University.

“He was one of the premier writers to ever go through the halls of The Daily Princetonian,” said Joel Samuels ’94, who briefly served as one of Wahl’s editors at the ‘Prince’ and officiated Wahl’s marriage to Gounder in 2001. “Within weeks of his arrival to the paper, he had quickly eclipsed the more senior writers.”

“The fall of 1992 was the apex of cross country coverage at Princeton, not because the team was particularly good, but because Grant was the writer,” Samuels shared. “His stories were so good that we ran longer stories on Mondays than we did on the football team.”

Nate Ewell ’96, co-editor of the sports section along with Wahl, remembered a particularly funny moment from their sophomore year that signified just how quickly Wahl had taken the paper by storm. Wahl missed part of that year due to an illness.

“I won the sophomore sportswriter of the year award, but there was a running joke, to the point that I think the Sports editor said it when introducing me: ‘Nate won this because Grant was ill,’” Ewell told the ‘Prince.’ “He was so good, and it wasn’t insulting at all. Obviously everybody knew that he was the best sportswriter we had.”

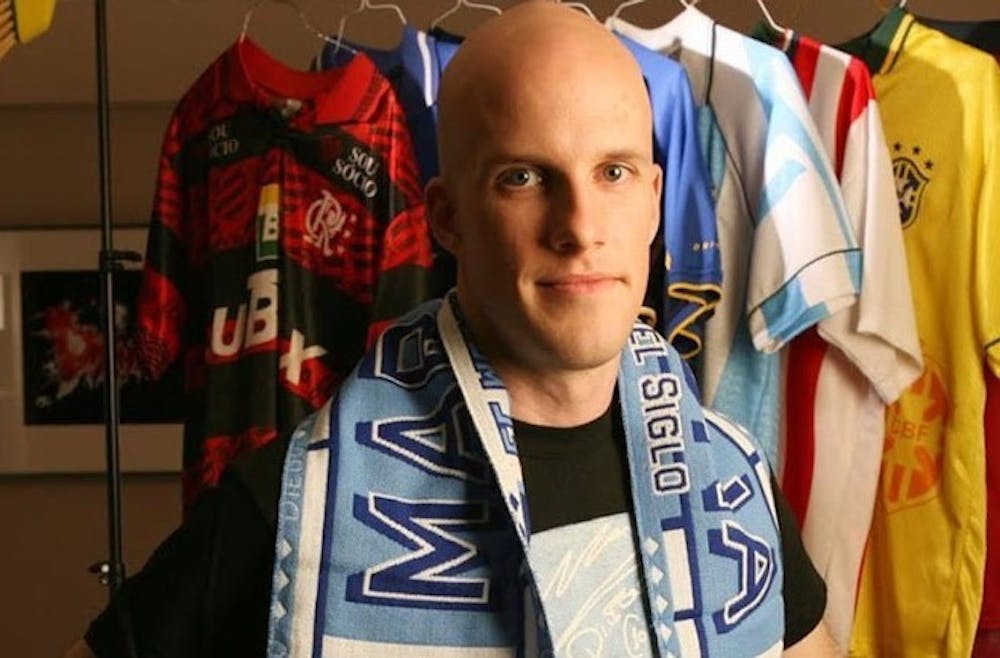

Wahl (right) with co-head sports editor Nate Ewell '96 (left) and deputy sports editor Malena (Salberg) Barzilai '97.

Courtesy of Malena (Salberg) Barzilai '97.

Other friends from the ‘Prince’ recalled the qualities that made Wahl’s writing so special, both while he was in college and in later years.

“Grant made sports writing about everything, and [believed] that it’s not just the back page. It’s the whole story,” said Allison Slater Tate ’96, a friend of Wahl’s who also wrote for the sports section. “That was his mindset from the get-go, and I think that’s what made him a brilliant writer.”

“He was a sports writer throughout his career, and for a lot of people that has a very particular place in their mind, which is telling stories about things that athletes have done,” Samuels said. “What is unique in the impact that Grant had is that he not only told stories about sports, but he also shared a broader context behind the sports. And whether it was soccer or basketball, he was always digging deeper.”

Wahl’s writing wasn’t the only thing that impressed his colleagues at the newspaper. Slater Tate recalls the special care and kindness with which he and Ewell treated their staff during their time as editors, often inviting the section to come together on Thursdays to enjoy drinks, pizza, and watch TV.

“It was a collegial atmosphere. It wasn’t just ‘file your story,’” Slater Tate said. “[Wahl and Ewell] cared about having a staff that they really wanted to cultivate.”

“Grant is a guy who is never looking for the more important person in the room. He treats everybody the same,” she added. “There isn’t a mean or snobby bone in his body.”

Wahl (second row, third from left) poses with other members of the 'Prince.'

Courtesy of Malena (Salberg) Barzilai '97.

‘Selfless in an industry where selflessness is not always rewarded’

Over the years, even as Wahl gained global recognition, his overwhelming kindness and generosity never faded. One former classmate at the receiving end of that generosity was Chris Long ’97, who enlisted Wahl’s help when founding his National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) club in Kansas City.

“I think there’s one individual that is credited with the growth and popularity of soccer in the United States,” Long said. “It’s Grant Wahl.”

“He, in particular, was a champion of women’s soccer from very early stages. That too needs to be noticed,” he added. “He always believed that the games should share equal footing. He used his platform, which was a big one, to advance those principles.”

Indeed, the impact Wahl had on the growth of the women’s game is immense — the tributes left by legendary U.S. women’s national team (USWNT) players like Becky Sauerbrunn, Mia Hamm, Abby Wambach, and others are testament to that. Long said that Grant was instrumental to the foundation of his women’s soccer club, the Kansas City Current, which finished as the runner-up in this past season’s NWSL playoffs.

“We were in the exploration phase, and he was our first call,” Long said. “Grant started texting everybody that needed to know about us and he kept telling them, ‘The Longs are real.’ He texted the commissioner, he texted the other owners, he texted other journalists … he was all over it.”

“There was nothing he was getting credit for or anything, he was just doing it because he believed in us,” Long added. “He [was] incredibly unselfish, and he [did] that stuff out of the kindness of his heart.”

Wahl’s generosity extended outside of the soccer business, too. Many who have come to know him through their work as journalists, including Sean Gregory ’98, who fondly recalled Wahl’s unrelenting commitment to mentoring the next generation. Gregory is a senior sports editor at Time, and also co-teaches a class on sports reporting at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

“Every year, Grant has either come and talked to the students, or was going to and had an unavoidable conflict,” Gregory said. “He was a busy guy, he was doing his own thing and trying to build a business, but he always had time to spend an hour and a half talking to students.”

“He’s done that with a lot of young reporters,” he added. “He was really selfless in an industry where selflessness is not always rewarded.”

To Wahl, giving back to the next generation of reporters was part and parcel to what it meant to be a good journalist.

“He recognized how hard a place [Sports Illustrated] was to be young at,” said Stone. “He wanted young people to know that they belong, that they didn’t have to apologize for being there.”

Adam Duerson, who joined Sports Illustrated in the early 2000s, remembers Wahl as one of the people who was instrumental in helping him settle in at the publication.

“[Sports Illustrated] used to be a very big place, and it was easy to feel like ‘I’m at the bottom. I’m not in the meetings. I’m not heard,’” Duerson told the ‘Prince.’ “When Grant Wahl took you out to lunch, or took you to watch a soccer game, you’d be a part of the conversation.”

“This felt like what [working at Sports Illustrated] was supposed to be like, and it empowered you in other corners, and to speak up and pitch,” he added.

A senior thesis on soccer, a love for Argentina, and a passion for social justice

Duerson was one of a handful of people at the magazine who were instrumental in facilitating Wahl’s switch to covering soccer full-time in 2009, rather than splitting his time between that and college basketball. This career move was something almost unthinkable even 10 years prior, when Wahl was just getting started at Sports Illustrated. In fact, according to Gregory, many journalists in the late-90s would not have even considered taking the soccer beat on a part-time basis, like Wahl did.

“Amongst people my age, in the late 90s, in the United States, it was not a sexy beat at all,” Gregory said. “The ’94 World Cup had just happened. MLS had just started. So there were rumblings, but he saw the potential, whereas so many in the country didn’t see the global possibilities.”

With Wahl having poured so much passion and dedication into growing both an audience for his soccer journalism and the American game itself, the decision to cover the sport full-time in 2009 ended up to be a roaring success.

“He ran with [soccer] like no American journalist did,” Gregory added. “He was just so ahead of the game on that.”

Wahl also took to the airwaves to cover the game as a correspondent for Fox Sports.

Courtesy of Stephanie Gounder.

Wahl’s experience reporting on international soccer extends all the way back to his Princeton senior thesis, which explored the confluence of politics and “fútbol” at soccer clubs in Argentina.

Carlos Forment, a former faculty member of the Princeton politics department and current professor at The New School, served as Wahl’s thesis advisor. Forment, a part-time resident of Buenos Aires, hosted Wahl during one summer in the Argentine capital while he conducted research at local clubs like the famed Boca Juniors.

Forment recalled the first time he met Wahl.

“Initially I was really, in many ways, very charmed by him, because he had this disarming quality. You know, the Midwestern quality, I had never really encountered close up,” Forment said.

Forment helped Wahl get settled in Argentina, but after the first few days, he was impressed with how the Kansan operated fairly independently and achieved spectacular results.

“He met with some of the most unsavory hooligans in Boca Club. I went with him a few times just because I was curious,” Forment said. “He charmed every single one of them and got interviews. That was not normal. You do not get interviews from hooligans.”

Coupled with fervent archival research, these interviews paved the way for Wahl’s thesis, earning him the Philo Sherman Bennett Prize in Politics, which is given annually to the junior or senior who writes the best essay discussing the principles of free government. He also earned the Stanley J. Stein Senior Thesis Prize from the Program for Latin American Studies.

“He saw [soccer] as a way of understanding civic institutions, you know, how people came together and organized and really what were the roots of social and political organizing,” Gounder told NPR. “That shed some light onto how Grant thought about soccer. It wasn’t just a sport. It was so much more. It had a much more important role in society.”

Even after his thesis was complete, Argentina occupied a special place in Grant’s heart. He often referred to it as his “adopted country,” and remained a supporter of Boca Juniors. In recent years, he had the opportunity to return to Argentina to film an episode of his show “Exploring Planet Fútbol.”

Steve Fainaru, an investigative reporter at ESPN who taught a sports journalism class at the University this past semester, met Wahl in Argentina during the production of the episode in early 2019. Before this year’s FIFA Men’s World Cup final, which Argentina won in a penalty shoot-out over France, Fainaru spoke to the ‘Prince’ about the few days the pair spent together in Buenos Aires.

“As it turned out, we were using some of the same crew for our pieces, and we were coincidentally also staying at the same hotel. So we ended up hanging out a bit,” he said. “He started telling me about Argentina, and his history about how he had fallen in love with the country.”

“I’ve been thinking about it now that Argentina is in the finals, the idea that he died while he was covering this World Cup, and that Argentina is now going to possibly win, and that he won’t get to see it,” Fainaru added, on Dec. 14. “It’s just heartbreaking.”

Four days after Fainaru spoke with the ‘Prince,’ Argentina won its third World Cup. And there’s little doubt that Wahl would have been overjoyed. But at this year’s World Cup, outside the on-field action itself, Wahl remained intently focused on human rights issues in the host nation: Qatar, where homosexuality is criminalized and thousands of migrant workers are alleged to have died while the tournament’s stadiums were under construction.

On Nov. 21, the second day of the tournament, Wahl made headlines for briefly being prevented from entering the stadium before the match between the United States and Wales for wearing a shirt emblazoned with the pride flag. Throughout the run-up to the tournament, he reported on issues related to migrant workers in the country. His last Substack post forcefully criticized Qatari officials for downplaying the death of a worker that took place during the tournament.

“He was a force for good in both our sport and our society,” said Jim Barlow ’91, head coach of Princeton’s men’s soccer team.

Jon Wertheim, Wahl’s longtime collaborator at Sports Illustrated, echoed a similar sentiment.

“Losing Grant is just that: a loss. An unfillable hole in the lineup — for journalism, and not least for humanity,” he wrote.

For Grant, the push for equal rights and human dignity was deeply tied to the goals of his sports writing.

He avidly covered the USWNT’s fight for equal pay, and even ran for FIFA’s presidency in 2011 in a bid to end rampant corruption. In a recent interview with CBS, Gounder expanded on the role that social justice played in her husband’s career and life.

“I want people to remember him as this kind, generous person who was really dedicated to social justice. I think that’s another aspect of soccer that was really important to him,” she said. “Promoting the women’s game, the recent statements he had made about LGBT rights. That was Grant.”

‘A true renaissance man’

After his passing, Gounder wrote on Wahl’s Substack about some of her personal memories of Grant.

“To know Grant was to know a true renaissance man; he was endlessly curious about the world, and a lover of literature, art, music, food, and wine,” she wrote. “He was equally in his element cooking a quiet dinner of sole provencal for two, walking his beloved Zizou and Coco through Manhattan, gathering friends for a raucous dinner party, and traipsing across Moldova chasing a story.”

The pair met at Princeton in 1995, when Gounder joined Colonial Club, where Wahl was already a member.

“Grant and I were really just kids when we met at Princeton. I was 18. He was 21,” she said at an event honoring her husband’s life on Dec. 21. “In many ways, we finished growing up together.”

Wahl and Céline Gounder met in Colonial Club at Princeton.

Courtesy of Stephanie Gounder.

Gounder wrote for the ‘Prince’ in 1994 for one semester as a news contributor, but the pair never met before she joined Colonial; according to her, during the semester she wrote for the paper, Wahl was on a leave of absence. However, she soon became aware of his passion for journalism.

At Princeton, Wahl took seminars with the likes of David Remnick ’81, editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, and Gloria Emerson, a New York Times war correspondent. Gounder recently shared a paper Wahl wrote on Emerson for Remnick’s class.

“He had just pulled out that folder right before he left for the World Cup to reread that paper,” Gounder told the ‘Prince.’ “[Emerson] was really one of the most formative people in terms of how he approached his writing.”

And although Gounder remains a casual soccer fan, she said the sport is not what drew the two together. She recalled witnessing Wahl develop a passion for the sport to which he would dedicate his life while at Princeton.

“Grant really fell in love with soccer when we were in college,” she told NPR.

“Part of the reason soccer was so important to him was it was the world’s sport. It was a way of understanding other people, other cultures, politics of different places, and really also understanding just the common man,” she shared with NPR. “Soccer is just the average person’s sport in most of the world, and it’s a great lens to get to know people.”

Wahl interviews Brazilian soccer legend Pelé.

Courtesy of Stephanie Gounder.

Those who came to know Wahl as a soccer reporter eventually came to see him as so much more.

“His great gift was that he was always kind. To everyone,” Mitch Henderson ’98, the head coach of the men’s basketball team, told the ‘Prince.’ “I got to know Grant best through Jesse Marsch ’96, and it was fun to see how the two of them interacted with one another, especially in the last couple of years with Jesse being in the Premier League and Grant being the most important soccer journalist in the U.S.”

Marsch, who is the manager of Premier League club Leeds United, recalled one of the things he loved most about Grant.

“I can hardly picture him without a smile,” he told the ‘Prince.’ “In a normal conversation, he was always on the brink of smiling or laughing. And that was infectious. I will miss him.”

To remember Wahl is to uplift a profoundly impactful and far-reaching journalistic legacy; even more so, it is to carry on the traits that defined his mark on the world: kindness, selflessness, and human decency.

“He was a great friend,” said Ewell, who co-led the sports section with Wahl during their time at the ‘Prince.’ “To be as good at something as he was, and to still be that great of a person, was really remarkable.”

Wahl is survived by his wife, Céline Gounder, and his brother, Eric Wahl.

Wilson Conn is a head sports editor at the ‘Prince.’ Please direct corrections requests to corrections[at]dailyprincetonian.com.