Everyone knows Princeton is rich. Its operating budget is over $2 billion a year, and it seems to be able to fund anything and everything it wants to. A few weeks ago, some of the now-ubiquitous loud construction disrupted one of my big lectures, and the professor quipped that extensive, inconvenient construction is “what happens when a school has too much money.” The whole class laughed, because we understood — we’ve all seen Princeton throw around millions of dollars. Like a dragon, the University has accumulated this ever-growing pile by following three rules: it doesn’t matter what or who is sacrificed to add to their hoard, the sum is never enough, and it is never significantly spent. For a more just and inclusive future, it’s time to change that.

Exactly how wealthy is Princeton? One measure is the endowment, which stood at $35.8 billion this October, higher than the GDPs of over a hundred countries. But the truly mind blowing number is the rate of return on investment: 11 percent per year on average over the last 20 years. The average real return for the market overall, approximated by the S&P market average, over the same time period was 7.93 percent per year. Just over three percentage points of difference may sound small, but since the rate compounds every year, the long term effect is huge.

This works magic for Princeton’s finances. The majority of the University’s income comes from endowment returns and other investment income, and that funding supports 66 percent of the University’s operating budget. Princeton’s other major sources of income totaled to just a billion dollars in 2019-2020, led by around $408 million paid by students in tuition and fees and $364 million brought in by research sponsorships. But again, this static snapshot of the University’s wealth obscures the most important part of the financial story — how fast that wealth is growing.

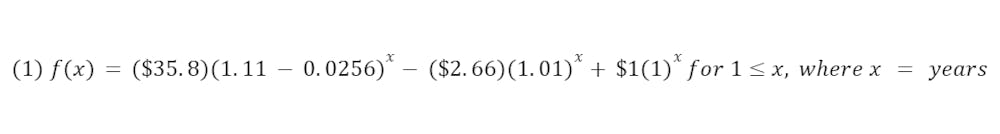

Princeton’s financial “perpetual motion machine,” as Malcolm Gladwell quips, is driven by three factors: a gigantic principal, astronomical returns, and low relative expenses. A simple exponential model (see equation 1 below) shows how it plays out over time. The first term is the $35.8 billion endowment principal, increasing at the average historical rate of 11 percent minus a long-term estimate of 2.56 percent inflation (average annual inflation 2002–2022). The second term subtracts the $2.66 billion operating budget, which is assumed to grow at an annual real rate of 1 percent. The last term is the University’s non-endowment income of around $1 billion, which is assumed to stay static.

Courtesy of Madison Davis

If this model is accurate, Princeton’s wealth will nearly double every 10 years, reaching $404.4 billion in 2053. Within 36 years, it would top the current estimated GDP of all of New Jersey and in about 45, it would reach above the current GDP of Spain, the fourteenth largest economy in the world. Our tiny university will own the equivalent of a large wealthy nation’s entire annual economic output within a few decades.

But while the University’s wealth skyrockets, its community and the world suffer because of it. It doesn’t have to be this way. Princeton’s resources are not scarce; they will never have a cash crunch. The University’s guaranteed financial comfort presents them with a huge opportunity to do good, and a moral imperative to use their privileged position to “serve humanity.” So, what would that look like?

Let’s start with the money Princeton takes from students. The full cost of attending the University, including tuition, meals, and housing, is estimated to be $79,540 — greater than US median household income. Princeton doesn’t release data on how many students get how much financial aid, but according to this year’s ‘Prince’ Frosh Survey, 42 percent of first years received partial aid and 40 percent no aid. Although Princeton is said to be “high-cost, high-aid,” their current plan is clearly inadequate: 18.3 percent of members of the Class of 2026 receiving partial aid and 12.6 percent of those receiving no aid anticipated taking out loans to pay for Princeton. And some admitted students, including one of my high school friends, turned Princeton down in part because of the cost.

The newly announced policy of full aid for students whose families make under $100,000 is not enough. Even a portion of $318,160 — the full cost of four years at Princeton — is a burden for all but the wealthiest families, like those in the top percentile of income (i.e., annual pre-tax income of about $600,000). And, as Community Opinion Editor Rohit Narayanan has argued in these pages, Princeton’s sticker price contributes to tuition inflation everywhere, including at colleges that give far less financial aid. But the tuition and loans many families sacrifice so much to pay mean next-to-nothing to Princeton’s finances. It’s time to eliminate or drastically reduce tuition.

Princeton is not only taking advantage of students and their families, it’s also short-changing staff. At the Council of the Princeton University Community’s November meeting, two facilities workers asked when non-union University workers would receive their 2020 raises, which were “suspended” when the University claimed financial uncertainty during the pandemic. (Union workers’ raises were guaranteed by a long-term contract.) Even though the endowment grew in 2020 and skyrocketed by 46.9 percent in 2021, non-union workers are still waiting for their raise. Why? The University has the money to pay their workers what was promised, and to ensure fair, timely raises going forward.

Princeton’s avarice also leads them to invest in and accept funding from companies and organizations that have clear conflicts of interest with politically sensitive research, creating ugly optics and potentially undermining credibility. Even after their recent partial divestment, the University still invests $700 million in private fossil fuel companies, despite these companies’ destructive climate impacts. Even more damaging, Princeton faculty accept money from fossil fuel companies, including BP, for climate research at Princeton’s Carbon Mitigation Institute, even though research shows that industry funding warps energy research.

Maybe Princeton University Investment Company is not convinced. Financially, what would a Princeton “in the service of humanity” really look like? Let’s update equation 1 (see equation 2 below). In the first term, the $35.8 billion in endowment principal, I’ve decreased endowment returns by one percent to account for a more ethical investing strategy and potentially lower returns. The second term (operating budget) is increased by an additional one percent per year to pay for staff raises and supplement research funding. Equation 1’s last term is eliminated: no tuition, no corporate funding, no outside research funding or alumni donations (a scenario that likely underestimates university wealth).

With this new model, the University’s wealth at the end of 30 years would be $303.4 billion, compared to $404.4 billion under the status quo. But these two scenarios are shockingly similar. Yes, in 30 years Princeton’s endowment would be $101 billion dollars less — but that’s $101 billion dollars that, under current rules, Princeton would not use. And the benefits of changing the way Princeton handles money — to students, families, faculty, staff, research, our spirit as a community, and our impact on the world — would be huge. Every Princetonian past, present, and future, could feel rightfully proud of their school, and Princeton would be set above its rivals: Not only exceptional and prestigious, but moral and welcoming, too.

Eleanor Clemans-Cope (she/her) is a first-year from Rockville, Md. intending to study economics. She spends her time making music with Princeton University Orchestra and good trouble with Divest Princeton. She can be reached on Twitter at @eleanorjcc or by email at eleanor.cc@princeton.edu.