Princeton invests so much effort into welcoming its new students that I probably couldn’t list every activity or resource offered to a matriculating student, but I found that, despite all this effort, the school doesn’t bother to always get one’s name right — not even when giving someone their netID and other web accounts that will unlock the next four years.

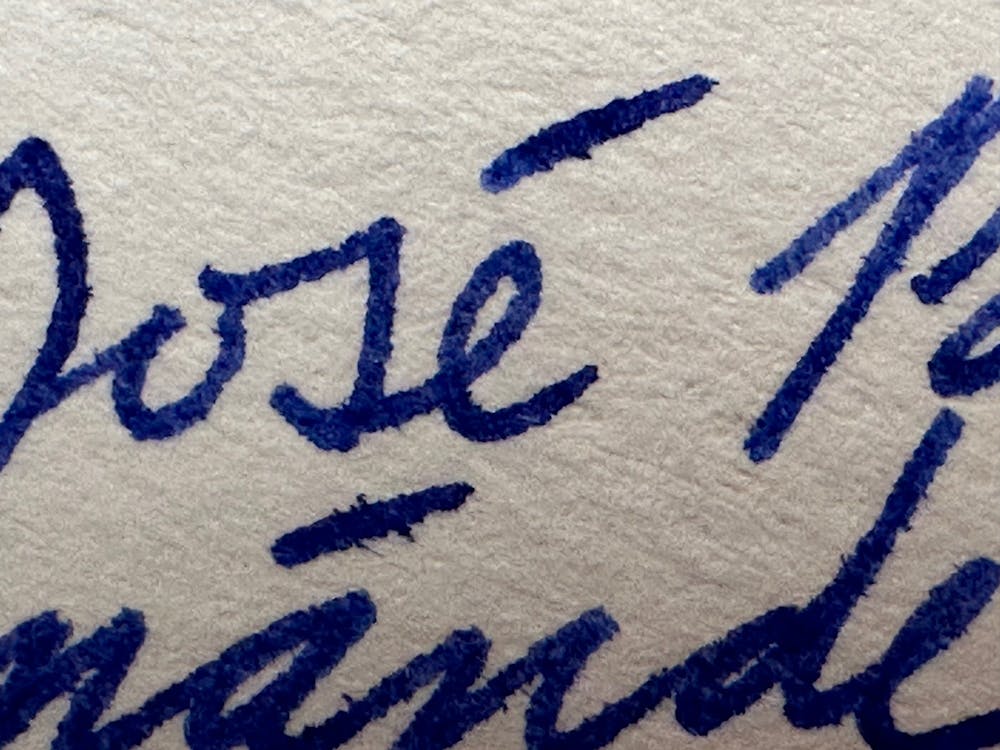

I’ve always had trouble with my name. Or really, others have had trouble with it. I mean, look at it: José Pablo Fernández García. It’s not exactly a friction-free name when growing up in southwest Ohio. It’s long: two first names and two last names (though, at least, no middle name) with almost as many letters as the alphabet itself. The correct Spanish pronunciation is something I gave up on outside conversations with other native Spanish speakers a while ago. And then, there are the three pesky little accents. They are such a small part of my name, but they carry so much weight for me. It’s not me without them.

However, much of the United States is clueless when it comes to diacritic marks. In fact, the country is a paperwork disaster for anyone who doesn’t have a Latinized, diacritic-free first, middle, and last name. It’s a wonder I remain only one person, given how many variations of my name I’ve been forced to jam into various forms and the like. Maybe most commonly, I’m forced to chop off the accents.

Sometimes, the form doesn’t allow spaces so I become Josepablo Fernandezgarcia. Sometimes, to get a space in my first name, Pablo must masquerade as a middle name. Sometimes, 24 letters is too many so some part of my name must be truncated. I’ve submitted countless variations of my name over the years. Mileage varies; the consequences range from funny to frustrating.

Recall the ridiculous amount of mail colleges might have sent you in high school. I received about three times as much. Because I took the PSAT in my freshman, sophomore, and junior year of high school. Because each year the answer sheet allowed a different number of letters in one’s name, truncating mine at different points each year. Because most schools didn’t address the fact that the three differently spelled versions of my name on their mailing list were all me. It was their money wasted on advertisements to schools I never considered.

At times it feels like the night I nearly had to abandon my friends at Charter’s doorstep too early in the night. The bouncers couldn’t find my name on the list no matter where they looked. They only kept looking because my friend, a member, insisted he had put me on the list. The bouncers seemed ready to tell me to go home, until finally they found me. That night I was Mr. Pablo Fernandez Garcia. I imagine a spreadsheet shortcut during the list’s preparation was likely at fault. There have been other nights when I’ve had to be Mr. Fernandez or Mr. Garcia. I’m none of the above; it’s Mr. Fernández García.

Stories like this came to mind when one of my Digital Humanities courses discussed Aditya Mukerjee’s article “I can text you a pile of poo, but I can’t write my name.” Our computers, in their fundamental processing of language, are not built for our names — built much less for his, originally not in the Latin alphabet, than for mine. It’s terrible to think of how often so many people are denied their own names.

I was nearly denied my own in my welcome to Princeton. The email with instructions to access my web accounts began: “Dear Jose Pablo FernaNdez GarciA.” At some point between my application and my technological matriculation, the accents in my name became capitalization for the following letters — save for the space following José. But it wasn’t just the email salutation: my name was like that in TigerHub. To avoid Jose Pablo FernaNdez GarciA attending Princeton in my place, I had to first call the Office of Information Technology and then the Registrar, only to then have to email the Registrar with documented proof of how my name is written. I asked for the weird capitalization to be removed and the accents to be restored; or at least the former, if not the latter.

To Princeton, I became Jose Pablo Fernandez Garcia. “Our system does not allow for letter accents,” I was told.

I share all this in anxious trepidation of my exit from Princeton. Last spring, I saw some tweets reporting that accents weren’t available for all styles of bound thesis covers — only some styles would allow me to accurately claim authorship. This made me wonder if my diploma will actually have my name — not some imposter’s. Now that’s a special variety of imposter syndrome.

At the end of the day, it could be easy to dismiss how some people are — how I am — forced to surrender our name to the whims of others, to their systems, to whatever they feel like accepting as a valid name. But in such a surrender, there is, at a deeper level, a certain surrender of dignity and identity as well. A name is so personal a matter; it should belong to no one but oneself.

So as I wait for others to recognize this, to call me by my true name, I make the adjustments I can. Because my name is nothing except José Pablo Fernández García.

José Pablo Fernández García is a senior from Ohio and a head editor for The Prospect at the ‘Prince.’ He can be reached at jpgarcia [at] princeton.edu.

This piece is part of a larger project highlighting Hispanic and Latine members of the Princeton community members. You can find the other pieces here and here.

Self essays at The Prospect give our writers and guest contributors the opportunity to share their perspectives. This essay reflects the views and lived experiences of the author. If you would like to submit a Self essay, contact us at prospect [at] dailyprincetonian.com.