In 1945, with enrollment up almost 50 percent since the pre-war era, the Class of 1915 committed to building a new dormitory. Because materials and labor were in short supply, costs ballooned. The quarry of Princeton stone had just been exhausted, so most of the walls were cheaper red brick. The building’s ornament included only a few pieces of trim, projecting dormers, and rounded archways. It was dubbed the “Poor man’s Gothic.” Somehow, even under difficult conditions, a building meant to house a burgeoning campus population was saddled with the legacy of the Gothic buildings on campus.

The expectation that new buildings be Gothic persists into the twenty-first century. In a recent Opinion Reactions piece, Contributing Columnist Julianna Lee ’25 wrote that she wants Princeton to build Hobson College in the Gothic style. Her language is almost apocalyptic: “If Princeton wants to remain Princeton, Hobson should be built to match the collegiate Gothic style of the buildings found north of campus rather than the new colleges.” However, architectural diversity is the hallmark of Princeton’s campus, and future buildings should continue this tradition.

This conflict between “the Gothic” and other styles on campus has been persistent since Blair Hall’s completion in 1897. However, what does “the Collegiate Gothic” even mean at Princeton? For University architect Ralph Adams Cram, the style signaled the continuity of Princeton with English universities, in contrast to the professional schools of emerging universities. President Woodrow Wilson 1877 agreed, stating during his tenure, “By the very simple device of building our new buildings in the Tudor Gothic style we seem to have added to Princeton the age of Oxford and Cambridge.” Wilson viewed Princeton as another English university, and, certainly, an only white university. Administrators and donors mostly concurred and thought that the Gothic architecture, picturesque views, wandering paths, and rural setting created an ideal environment for receiving a liberal arts education.

Despite symbolic motivations for these buildings, the architectural historian Donald Drew Egbert ’24 GS ’27 pointed out in Princeton’s bicentennial year, the Gothic buildings at Princeton are “far from being historically imitative.” In an extremely close analysis, he explains that flat rooflines, open courtyards, and blocky forms are not characteristics of any Gothic building of the 14th century and are more results of the logistical needs of the University. Egbert links formal differences like open courtyards in dormitories and larger office and meeting rooms in classroom buildings to the educational independence that Princeton provides in contrast to other institutions — an independence developed by precepts and the thesis.

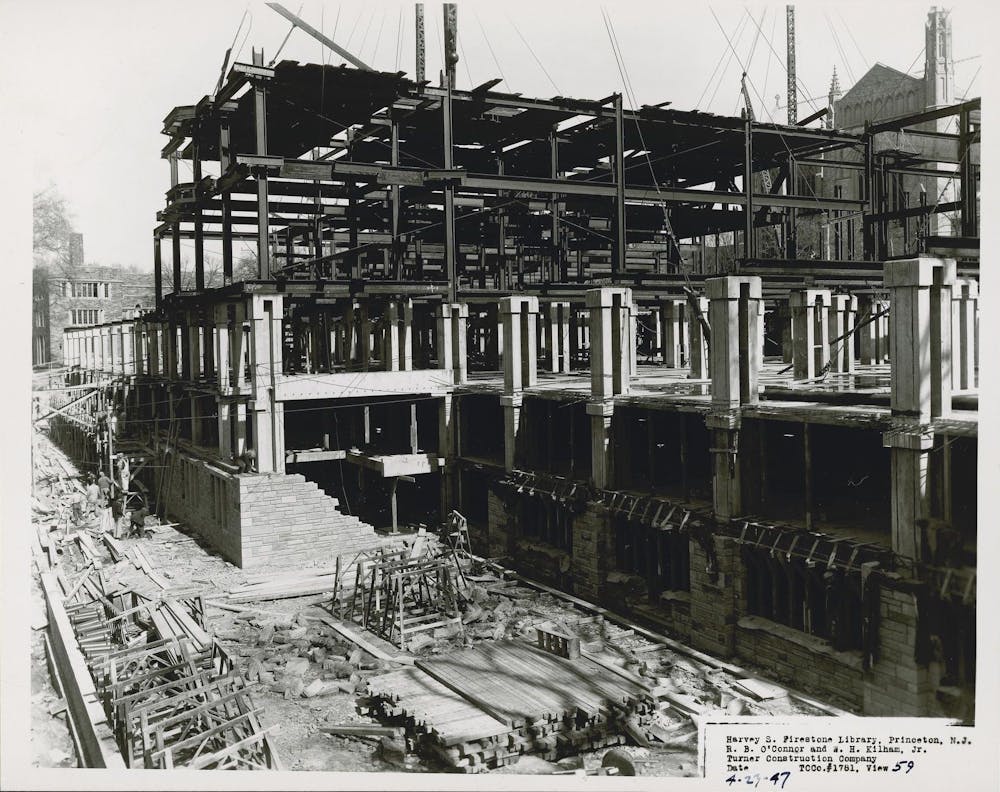

Egbert has highlighted a key point. Princeton’s brand of Gothic was actually very adaptive to different site conditions, different programs, and different eras. Firestone Library is thought to be Gothic despite its giant, blocky plan and sparse detailing. But to me, the best symbol of the history of the University and independence inherent in our education is the diversity of buildings on campus. Would we really want an exclusively Gothic campus? Princeton has slowly grown and evolved; its architecture now naturally reflects this progression.

Similar to Egbert, I believe that we love Blair Arch because it is well integrated into the landscape, has an optimal location, and has a monumental form appropriate for an entry to campus, not because of the richness of its Gothic detailing. This building is well executed, as are many other buildings on Princeton’s campus.

But some buildings have not been so carefully considered. The buildings of First College, the Engineering Quad, and old Butler College were constructed during a time when Princeton struggled to fund the expansion of the University. Like 1915 Hall, many of these projects suffered. President Goheen recalled in 2004, “we still felt desperately short of money, so we took the cheap way as it were.” These projects were noble in goal — to resize the campus after the stagnation of the Great Depression and World War II — but they were poor in execution.

The differences lie in the care of planning, materiality, and durability, not in stylistic choices. Can Gothic ornaments be really essential to a successful campus building when virtually no student can cite precedents of the English Gothic style outside the fictitious Hogwarts?

We would not like a campus on which we could only study one language, one style of music, or one era of film. Princeton prides itself on its liberal arts education: A diverse architecture is a physical manifestation of this belief. Architecture that spans 266 years allows for examples of construction from across that timeframe. Seventy-five years ago, Egbert saw this too. He wrote: “Some such diversity is important for encouraging the sense of responsible freedom which Princeton seeks to develop.” Since 1946, the campus has become dramatically more architecturally diverse.

Symbolically, the full campus acts as a record of the history of the University. Standing in Scudder Plaza, a student can see an innovative Gothic form from 1907, a vaguely Gothic lab from 1929, a restrained classroom building from 1952, and a modernist temple from 1965, among many other styles and combinations throughout campus. The juxtaposition of these buildings allows for a familiarity with the history of Princeton that would be impossible to capture in any text.

Thus, Hobson College should be built durably and sustainably to relate to its context while expressing the time when it is built with contemporary materials and methods. Just like all buildings on campus, it will be a record of its own construction. Diverse buildings on campus allow students to contrast design approaches and to view Princeton’s history.

In the same 2004 interview, President Goheen commented, “among alumni you find out that the older they are, the more intense is their feeling that the campus was perfect in their day.” Somehow students are now not only conservative but reactionary in their approach to architecture. Wonderful buildings and contrast exist on Princeton’s campus. Hopefully, more will continue to be built, but these moments will come from great execution of the buildings, not a universal application of a single style.

John Raulston Graham is a junior majoring in architecture from Portland, Tenn. He is the Orange Key Guide Service historian and a member of the Princetoniana committee. He can be reached at jrgraham@princeton.edu. Graham is a former features writer for the ‘Prince.’