On a stage fizzing with the magic of a composer’s, poet’s, and performer’s talents uniting into a single voice, a lone soprano sang: “the pause between the flash of lightning and the thunderclap / is the time we have for reading / ‘the thunder of the present.’”

This moment from Francisco del Pino’s musical exploration of Victoria Cóccaro’s poem “The Sea” is one of many that remained with me as I left Princeton Sound Kitchen’s recent performance, “New Works for Voice” on Sept. 20. As I wandered a few doors down the hall from Taplin Auditorium to the Mathey College Common Room, I felt the faint rumble of the experience freezing into memory. Moments before, along with a vibrant crowd of fellow music lovers, I had witnessed a rare flash of artistic genesis, as momentary as lightning, but one which I will not soon forget.

On the program were five compositions making their first forays into the world, all by Princeton University graduate students and faculty composers. The marvelous lineup of performers included soprano Charlotte Mundy and performance faculty member and mezzo-soprano Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, alongside Princeton University Orchestra Conductor and Director of the Program in Music Performance Michael Pratt directing instrumentalists from the Princeton performance faculty.

The event opened with graduate student Christian Quiñones’ “My voice is a broken chorus.” I was fascinated with Quiñones’ fragmentary vocal writing, in which pitches surfaced like shards of colored glass amid a wild electronic soundscape. This approach allowed Quiñones to express a kaleidoscopic identity in the solo soprano, constantly fracturing and recombining in new ways. As the piece progressed, the strident texture of the first movement gave way to a dream-like lyricism, made buoyant by waves of electronic sound. I felt like I was listening to a voice totally lost in space, experiencing the pain of a self whose fragments pull apart.

Next was the screening of Hope Littwin’s GS experimental work “In the Company of Crisis, Songs of Communal Becoming,” which fused movement, voices, and film. In a short introduction, the composer gave us “permission to giggle” as we experienced a range of vocal sounds beyond our wildest imaginations in celebration of the “fierce fun” that is integral to her art making. In her program, Littwin asked, “What kind of deep euphoria could come from returning to the body as source composer?” As I listened, I caught a few glimpses of this euphoric realm, where the physicality of musical expression is fully embraced — where music is not only something we do, but something we are.

After this, Mundy once again took the stage for graduate student Francisco del Pino’s piece “The Sea,” written for a solo live voice and pre-recorded voices. Before the performance, del Pino remarked that while writing this work, he didn’t feel as though he was composing “The Sea” so much as musically interpreting Victoria Cóccaro’s poem by the same name (translated from Spanish by Rebekah Smith).

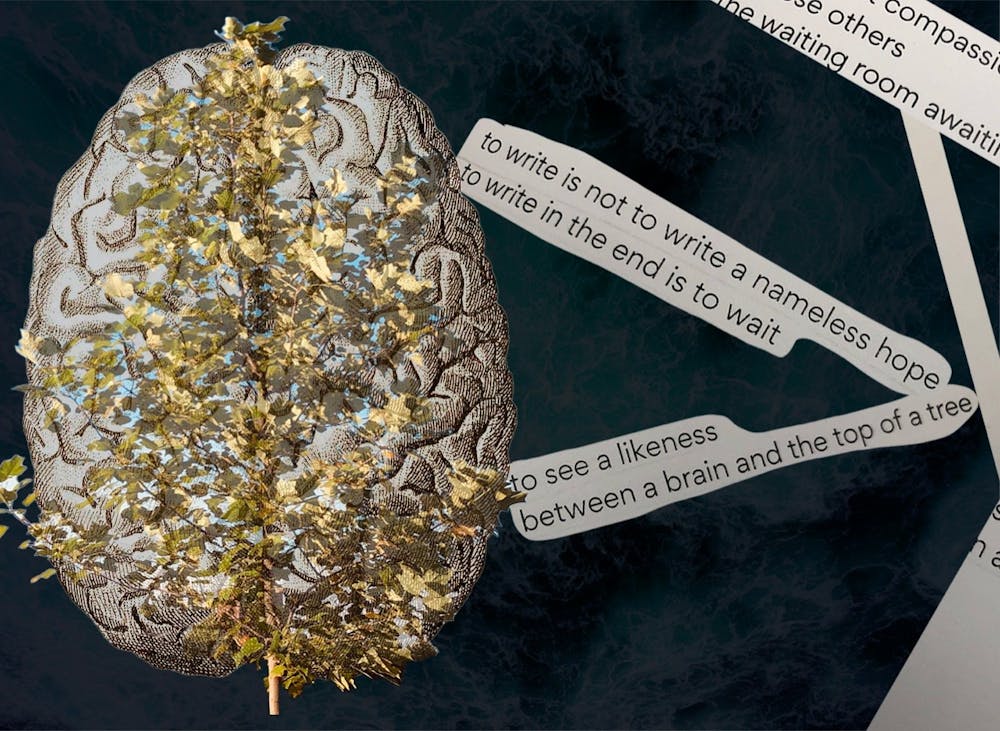

Indeed, during the performance I felt that del Pino was constantly in conversation with Cóccaro. In the first part of the piece, the solo soprano intones Cóccaro’s text as a one-pitch melody — a musical axis around which pre-recorded voices orbit, singing the lines “the sea shifts like / thought / like thoughts / when you think under water” in ever-changing rhythmic and harmonic combinations. This compositional juxtaposition of an individual against a shifting background resonated powerfully with the text. Indeed, in the poem, a nameless identity reflects repeatedly on the act of writing, as in the beautiful lines “to write in the end is to wait / to see a likeness / between a brain and the top of a tree.” Alongside this thread is a vivid evocation of the passage of time as a continual process of renewal: “in all things there is water / all the time the sea / that is always beginning.” In the second half of the composition, the soprano abandons her one-pitch melody, sinking into the texture of the pre-recorded voices — a self dissolved in the hypnotic peace of an eternally shifting sea.

After a brief intermission, singer Iarla Ó Lionáird and harpist Parker Ramsay performed graduate student Connor Elias Way’s arrangement of “Táimse im’ Chodladh,” a traditional Irish sean-nós song. Ramsay’s delicate accompaniment perfectly highlighted the raw emotion in Ó Lionáird’s voice, as he declared in song: “Would that I see the day when the English were bent over and they plowing and tilling for us.”

The final work on the program was Research Specialist Andrew Lovett’s opera in one act, “Sinuhe,” based on a nearly four-thousand-year-old Egyptian poem that tells the story of an official who flees Egypt in panic when he hears the king has died. At the end of his life, plagued by the guilt of killing a man in exile, Sinuhe seeks his homeland once again to prepare for his burial.

In a conversation with him before the performance, Lovett said that Sinuhe “is grappling with who he is. Questions of identity are … right there.” This intrigued Lovett because, in his own words, “opera is very good at dealing with a person who is at war with themselves.”

Indeed, in this chamber opera, Lovett explores the many internal and external conflicts in “Sinuhe” through what he calls “music theater,” or the treatment of musicians not just as ensemble members, but as agents in the drama. Lovett noted that the cello, bassoon, and bass clarinet “are always almost arguing with each other,” adding that “you make magical things happen with that combination … having instruments on stage — it’s inherently theatrical.”

I noticed this theatrical dynamic vividly during the fifth movement of the work, in which Sinuhe tells of the fight in which he killed a man. After each bit of text, the instrumentalists respond, like courtiers gasping after each harrowing detail, or groaning in anxiety as Sinuhe’s heavy guilt surfaces.

Lovett said he is drawn to small-scale opera because “you are in a small enough space where you can really feel like … everyone is in the same physical, metaphorical, and dramatic space. The whole space is the theater.”

But for all the fascinating compositional and theatrical details in Lovett’s work, he feels this machinery exists in the service of a broader end: “I think of it as storytelling first and foremost, and I want people to just get so caught up in the story that they don’t really notice how it is being told,” he said.

It was clear from the enthusiastic applause that Lovett had accomplished this and more as he transported all of us in the audience four millennia into the past to show us an image of ourselves.

The variety of artistic visions on display at “New Works for Voice” exemplified classical music as a living art form, continually being reinvented much like Cóccaro’s sea “that is always beginning.” As I confronted five soundscapes unlike anything I had experienced before, I couldn’t help but feel the vastness of the universe of all the music, language, images, and ideas that have yet to be imagined. Perhaps art’s virtue is to inspire us to explore some small fraction of that secret expanse.

Jack Gallahan is a contributing writer for The Prospect at the ‘Prince.’ He can be reached at jg8623@princeton.edu, or on Instagram @jack62832.