The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone. For information on how to submit to the Opinion Section, click here.

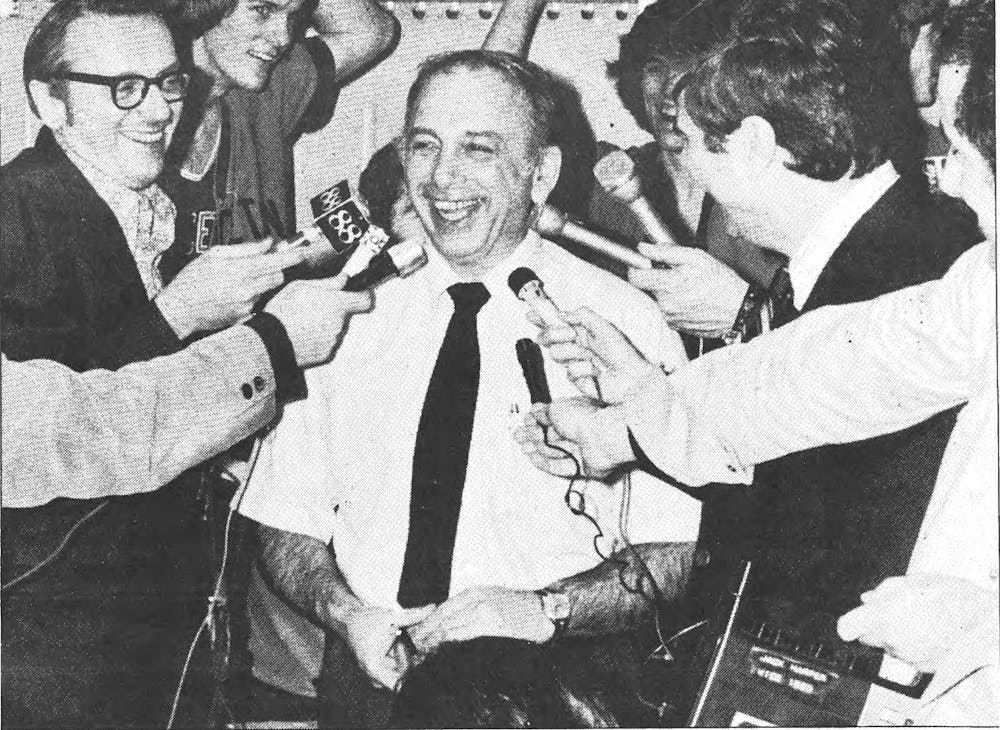

The passing of Pete Carril, former head coach of the Princeton University men’s basketball team, has sent shockwaves through the basketball world, inside and outside of Princeton.

His fabled Princeton offense, ruffled appearance, good nature, and legendary teaching skills left an impact on all those who knew him, along with those who didn’t.

Fourteen years ago, as a senior at Georgetown University, I sat in a library, trying to come up with an idea for an all-important senior thesis project for my American Studies degree.

In my spare time, I was studying the Princeton offense and playing basketball every day as I prepared to try out for the Georgetown University basketball team, one that was then coached by the Carril-trained John Thompson III ’88, only a year removed from a Final Four run, and the only team in the fabled NCAA Big East Conference to run the Princeton offense.

What I realized was that while many respect the Princeton offense as a way of playing basketball, it has much deeper resonance: its tenets of a focus on individuals, empathy, and trust are the bases of all good organizations. And most importantly, the romanticism of Carril’s Princeton fighting a David vs. Goliath battle in the 1996 NCAA Tournament holds an inspiration for modern social movements and campaigns.

I decided to write my thesis on the parallels between Carril’s Princeton offense and the most exciting campaign of the day: Illinois Senator Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. Less than six months earlier, Obama had toppled heavy-favorite Hillary Clinton in the Democratic presidential primary, and the buzz of his campaign was gaining momentum in Washington, D.C. as the election drew nearer.

To understand the connection, you have to understand how Carril worked. As a coach, Carril focused heavily on individual players. Sean Gregory ’98, the sharp-shooting wing of the 27–2 1998 team and a role player on the ’96 team, relayed a story featured in my thesis to illustrate the point. He laughed as he remembered Coach Carril relentlessly drilling Mitch Henderson ’98, the team’s star point guard, now Head Coach, in weak-hand passing drills that might not even be seen at a youth basketball camp, much less the practice session of a Division I program.

“It would be very simple,” he said. “Mitch and a teammate in the opposite corner. [Carril would say] ‘Mitch, 30 times, throw that pass to the corner with your left hand.’ Nobody ever practices that! Nobody ever practices weak hand passing like that. But it was something very specific. And they would practice that very specific move, which isn’t complicated, but takes practice. It’s hard but if you practice it enough it works.”

John Rogers ’80, captain of the 1979–80 Princeton basketball team (and coincidentally also Obama’s campaign finance chairman in Illinois), relayed a similar sentiment from his experiences. He said that Carril “could tell each player what they were thinking when they did what they did … that’s hard to do. That’s hard just to remember where everyone was, let alone remember what they were thinking, and get into their head and visualize what they visualized, and then help shape that vision so they don’t make the same mistake again.”

The core of Carril’s management philosophy was trust. On Feb. 25, 1975, the Princeton Tigers played a highly ranked University of Virginia team in Charlottesville, Va. At the time, all of Carril’s assistant coaches were out recruiting, and Carril was the only coach present. With Princeton clinging to a 35–29 lead with 15:00 remaining in the second half, Carril was ejected from the game for arguing a call. Coach Carril then put the team into the hands of substitute Peter Molloy ’76, and the Tigers would go on to win the game 55–50. The game propelled the Tigers into the National Invitational Tournament, which they would eventually win. Carril called the Virginia game the “highlight” of his career.

As another example, a year after Carril’s retirement in 1996, newly-appointed head coach Bill Carmody was in the process of leading his Princeton team to a 27–2 overall record when they matched up against Niagara University in the finals of the ECAC Holiday Festival at Madison Square Garden in New York. At one point in the game, the Purple Eagles switched to a triangle-and-two defense, a rare defense few practice to beat. During a timeout, several of the Tiger players asked Carmody how they should counter the defense. Carmody responded, “You are smart guys. You figure it out.” Not only did the Tigers go on to win the game 61–52, but they scored every single basket off of an assist, 21 in all. After the game, Niagara coach Jack Armstrong commented, amazed, “To score every basket off [of] a pass is picturesque.”

One also shouldn’t minimize the inspirational value of Carril’s signature upset — the 43–41 toppling of blue-blood heavyweight UC Los Angeles in the first round of the 1996 NCAA tournament, punctuated by, what else, a backdoor layup with 3.9 seconds left.

Carril’s effects were felt much further than just the result of the games he coached, or the famous upsets he nearly pulled off, or the one famous 1996 upset he did pull off. He was not just an old guy from a little underdog school who finally got the big win. He was clearly much more than that.

As Rogers told me in 2008, “He taught you so well… made you understand so well, that [I] can play with guys who played in 1972 to guys who played in 2002 [from Princeton] and we all see the same things… His legacy still lives, it’s been passed on from generation to generation.”

I saw all of these things in the Obama campaign. Carril’s empathy and focus on each individual player were mirrored in the Obama campaign’s individual voter outreach and micro-targeting — trying to reach people where they were. Obama’s appeal, in the words of campaign manager David Plouffe, was based on the trust of the voters, who thought he told it straight. And it’s hard to remember, but at the outset, Obama’s campaign was the longest of long shots — a Cinderella story. There were even some common characters: along with John Rogers, Michelle Obama ’85’s brother Craig Robinson ’83 played under Carril.

The Obama campaign is long behind us, and so is my thesis. I had forgotten about my senior thesis until I read the news of Carril’s death. The project was important to me: it filled a void after I was cut from the Hoya program a month after coming up with the idea. I was never coached by Carril, or Thompson, but in some ways, by the end of it, it felt like I had been. Either way, the descriptions of Coach from his former players had led me to believe he would have liked to read my paper. Even if only to have a good laugh and give me some pointers.

Mike Kentz is a journalist, high school teacher, and coach based in Savannah, Ga.