“Я люблю тебя.” I love you.

The reply pops onto my screen within seconds.

“И я тебя.” And I you.

I have never been comfortable with the word love. My family never made the casual habit of it, never used it to punctuate a phone call, but in Russian, I have acquired a clumsy assertiveness, a bold naivete only permissible for foreign language beginners. I’m a babbling child again, learning a new emotive world through trial and error.

I’ve been practicing with my old piano teacher, Anna, with whom I recently got back in touch.

My grandparents enjoy reminding me of the day Anna and I met — my 8-year-old sister had just begun piano lessons, but I, at 4 years old, was considered too young to play. So, like the spoiled brat I was, I bawled in the waiting room until they let me sit next to my sister on the bench. In light of my jealous desperation, Anna invited me to clap along to a few basic rhythms. Giving in to my snotty pleas, she took me on as a student.

I was no prodigy. My beginner’s enthusiasm was not paired with the discipline necessary for regular practice. And besides, when asked to play in front of anyone besides Anna or my family, my body would vibrate head to toe with poorly suppressed terror.

“Lazy, lazy girl,” Anna’s voice still echoes in my mind. “So talented, so lazy.”

As I got busier at school, I got even lazier. I disappointed Anna every dreaded Monday. My desk drawer is full of bronze medals and honorable mentions from local music competitions. And besides, if I wasn’t good enough at piano to help me get into college, what was the point?

One Monday, during the beginning of high school, I told Anna I was quitting.

“I can’t believe it,” she said. “After ten years.”

After that day, our interactions were limited to clipped birthday wishes on Facebook. She must’ve been busy with other students, but it feels so odd now, or maybe even cruel, to think of how I visited her once a week for what had practically been my entire life, and then never saw her again.

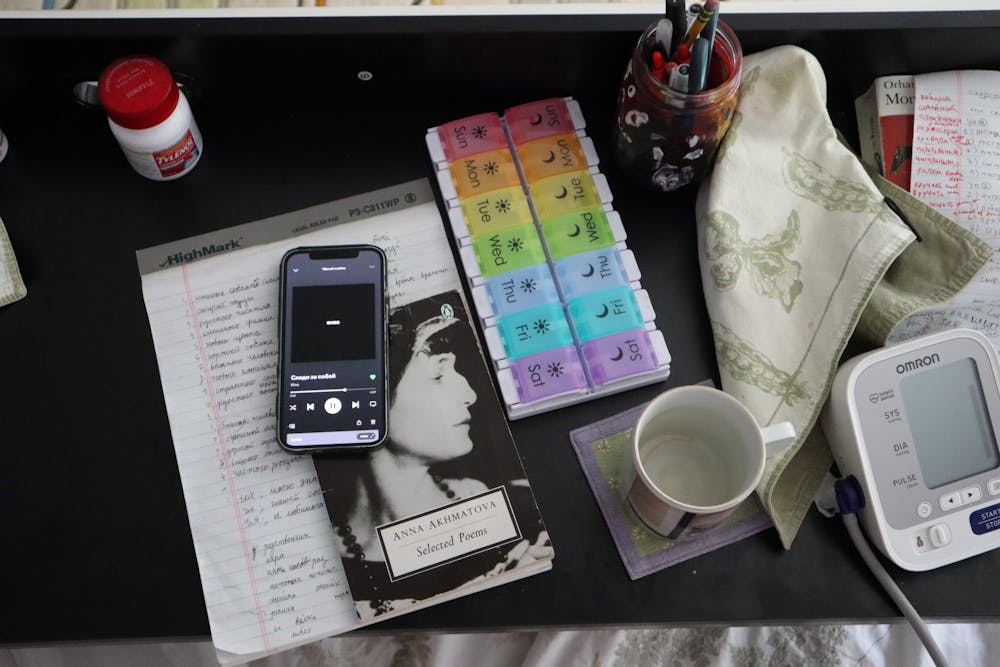

But after wishing her happy birthday this past May, I told her that I was on medical leave, and would be back home for a while.

“Ellen, what’s wrong?” she wrote back. “Are you able to continue your college? I’m so sorry I haven’t seen you for such a long time.”

I told her that I’ve suffered from chronic fatigue syndrome for the past six years. It’s a neuro-inflammatory disease where symptoms can worsen dramatically with exertion. Last fall, I knew my body was failing to keep up with the demands of the in-person semester, but I was determined to finish. By late November, I was vomiting every other morning, delirious with pain for eight hours a day. By finals, I could no longer get out of bed. After a few days as a prisoner in my room, I called my family, begging them to take me home. I emailed my professors, asking whether they’d pass me with D’s if I handed in blank finals.

A few months later, I learned that I also have an arteriovenous malformation, a tangled mass of blood vessels in my brain that puts me at high risk of seizure and hemorrhage.

I thought of my near-daily unilateral migraines. I thought of the time I woke screaming at 4 a.m. with the worst headache of my life, half-numb, periodically unable to breathe, and Snapchatted all my contacts, “hear me out I think I’m having a stroke,” and “this is weird but you’re a great friend and I love you.”

That day, the ambulance declined to arrive, not believing someone could have a stroke at 21 years old. After a taxi ride to the hospital and a 10 hour wait, I was sent home with 500 milligrams of Tylenol and a negative pregnancy test.

“OMG!” Anna texted me after I described my diagnosis. “Never thought something bad could happen to you.”

A few days later, she sent me a link to “Rachmaninov Concerto 2,” played by Evgeny Kissin.

“It will make you feel better,” Anna wrote. “Listen to music, it will bring you to fairytale world, wonderful adventure. You will be Ellen in Wonderland! (Alice)”

It’s true that, when I am able to listen, Rachmaninov carries me far away. But what I don’t tell her is that I am often too nauseous for sound, that even the stubborn thrum of my heart is sour in my throat as I lay in the dark, unable to move, speak, or think. These times — these lacunae, long passages blacked out of my stream of consciousness as if my brain were half-bathed in ink — remind me of Ionesco’s play, “Le Roi se meurt” (Exit the King). The king gradually loses control over his kingdom, his subjects, his limbs, and finally, he loses sight and speech. The queen cuts the invisible threads which tie him to the world. Curtain. For most of my waking hours, I think Ionesco would pronounce me dead.

But if that is death, what is life? As the king says, “Il n’y a que la littérature.” There is nothing but literature.

Maybe I find this persuasive only because my life is so materially null. My horizon is my bedpost. But could it be that literature is all there is — not just as in poems and novels, but as in expression by means of language? When I am not living in literature, I am living in the nothing that is the absence of signs, the almost-nothing of despair. Living as a spectator of this shoddy art house film that may or may not be on pause, static hours gathering like dust on eyes pried open.

When the fog clears, I am always starved for literature.

So, you can imagine my terror, when they found the blot on my brain MRI, sitting in an area which, I learned from panicked Googling, was near my center of emotive language processing.

“I wonder how many of my personality flaws I can blame on this thing,” I texted close friends. “Is this a valid excuse for being an angsty little bitch who writes shit poetry?”

![By candlelight sits an open book. On the left is Mayakovsky’s poetry in Russian and on the right, the English translation. Next to the candle is a mug with the following text written in black bubble letters "They told me I could be anything, so I became a [unintelligible text]"](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/pri/11ab5e9a-bcd2-4631-97a2-098ff86fffc5.sized-1000x1000.JPG?w=1000)

Mayakovsky’s poetry.

Ellen Li / The Daily Princetonian

After we reconnected, Anna offered me free piano lessons. She’d moved into a senior living community and looked almost the same as I remembered, though her hair was maybe whiter.

When I asked her how she’d been, her answers were brief. She’s not so busy during summertime. She returned the question, and I said I was alright, just tired and happy to see her. I described a bit what my days were like, but she said nothing in response and invited me to the piano.

I wondered if there’d always been a language barrier between us, that I had overlooked in my impenetrably bashful youth.

She’d switched out the piano bench for a tall-backed chair with pillows. I warned her that it had been a long time since I played, but she wouldn’t have it. She put Medtner’s “Skazka Ptichek,” “A Bird’s Tale,” before me, and I sight read through, my fingers slow and halting over foreign chords. As the piece ended, silence flooded the space between us. I was certain she must’ve been looking for something less than rude to say. Then, I met her eyes.

“I’m so proud of you,” she said. “I’m proud of me, for teaching you something you remembered.”

Professor Mark Pettus’ Russian lectures.

Ellen Li / The Daily Princetonian

I started learning Russian on a whim. My sister suggested I learn Turkish with her, as a way to structure my bedbound days, to exercise my mind without exhausting it. But the Turkish course cost money, and I found Professor Mark Pettus’ Russian lectures online for free.

The daily lessons brought order to my life, which had begun to resemble a heap of dead time. If I could do nothing else in a day, at least I had 30 minutes of grammar drills under my belt.

I surprised myself with my consistency. Having completed half a semester’s worth of lectures in a month, I even decided to find a tutor online, Sergey, a language-learning enthusiast from Kazakhstan.

Though I could hardly speak a simple sentence in Russian, and just barely managed not to mangle my first ever ‘privyet’ to a living, breathing human being, I was incredibly excited to have toddler-level conversations with a stranger across the world. Every new expression learned was a gift, no matter how banal. ‘Kruto,’ cool, ‘tak tak tak,’ well well well, ‘mozhet byt’,’ maybe.

But as my vocabulary grew, the world widened, and my bedroom seemed to shrink. Russian filled me with a longing for elsewhere. I resented my failing body that could hardly sit upright for an hour, let alone survive anywhere outside my family’s suburban home.

I found another way to feel like a foreigner, to feel out of place as my body stayed obstinately in place — trudging through Russian poetry, deciphered one word at a time. I will proudly declare myself a Mayakovsky fanatic, despite having read maybe five of his poems. His last poem, the unfinished epic “At the Top of My Voice” (1930), quite literally transports you across space and a century:

My verses will reach

over ranges of ages

over the heads

of poets and governments.

My verses will reach you

but not like so –

not like an arrow

of cupid’s hunt

not like a worn penny

to a coin collector

and not like light

from dead stars.

My verses

labor

to cleave the mass of time

and will appear

in bulk

coarse

clear

as aqueducts

which entered our days

still built

by Roman slaves.

“Is it weird that I think I have a crush on the Russian language? I swear it’s not sexual,” I texted my friend, who’s also a comparative literature major.

“No yeah, I feel the same about Portuguese,” he replied. “But for me, it’s definitely sexual.”

After a few weeks of practice, I gathered my courage to text Anna in Russian.

“Do you know this poem by Akhmatova?” I wrote, along with an English translation I found of “White Night” (1911). “Ya eto obozhayu!”

“Your Russian is perfect,” she wrote back. “We can trade: You teach me English, I teach you Russian! Translation of White night is awful.”

I replied with a misspelled ‘spasiba,’ and the next time I saw her, she asked me to read “White Night” aloud to her, though I recognized less than a quarter of the words and pronounced none of them correctly. She drilled me on it as if it were a piece, asking me to repeat line after line back to her, because she wanted me to “feel the music”: its steady rhythm and ABAB rhyme, neither of which the English translator chose to preserve.

“Do you understand?” she asked. “Maybe you can translate it when you get home.”

I did translate it, intending the translation as a kind of gift for her, an assurance that I did understand, that I could feel Akhmatova’s tired heartbeat, bitter longing, and sharp turns.

Ach, I haven’t locked the door,

I haven’t lit the fires,

you don’t know how worn

I am, that even respite tires.

Watching lines abound

fade to pine and sunset blurs,

I am drunk on a voice that sounds

like yours

and know that all is lost,

to live is to burn

in hell. I would have crossed

my heart on your return.

“But Ellen, Akhmatova is not the poet you need to read. Her life was a pure hell,” Anna told me. “Russian poets are heavy drinkers. They looking for a better life in a glass of vodka. You need to read some other poetry, bright and optimistic!”

The next time we met, she pulled out a worn volume of Bella Akhmadulina, and showed me “Chopin Mazurka” (1958).

What a fate was ours,

how fortunate this hour

with only the spinning record

between us!

First emerged a hiss, thin

as a garter snake from its stone lair,

but strokes of Chopin

soon gathered in the air

and swept, steep, steeper,

and pledged: a reckoning,

and so dispersed these rings

like ripples in water.

And as thin as a test tube

of water light blue

there stood a mazurka girl

shaking her head.

How did she, her frame

paltry and face a Polish white,

unravel my woes and claim

them as her own?

She cast her arms wide

and faded beyond reach

as all sound was swallowed

into the needle-scarred ring.

“You see, music takes away all worries,” Anna said, after describing the girl in the poem’s fantasy — deceptively frail, but beautiful and wise. “Music will take away all your worries.”

I was at a loss for words. I felt tremors rising in my chest, a feeling warmer than my usual anxiety in her presence. All this time, had she been trying to say something to me through her choice of music, like she did with her choice of poetry? A decade’s worth of repertoire. For so long, I saw these as tedious assignments, emblems of my insufficiency as a “lazy, lazy girl.” I was ashamed that I never felt the poetry in music as I now felt the music in poetry. That I had always read the staves like a machine. That I internalized Anna’s scolding more deeply than I did the many times she told me that she loved me like a granddaughter, that I was so talented and beautiful and all she wanted was for me to be strong and happy.

As furious as she seemed while correcting my phrasing of Granados’s “Spanish Dance: Andaluza” — why are you slowing down, do you see a ritardando? — she swore she wasn’t upset with me, only worried that I’d somehow turned a passionate love song into a “funeral march.”

It struck me how poorly I must have understood her, as we conversed for years primarily through piano, a language I never put my heart into learning. I wanted, so badly, to make it up to her.

On my next visit, I handed her my poetry translations. She looked up at me in confusion.

“You want me to find originals for you?”

“No, no, these are the ones we read before.”

“Okay,” she said, setting the page down on a pile of sheet music. “How’s your Czerny?”

Although I had been more determined to practice than ever before in my life, the Czerny was not going well. With fortissimo chords over allegro runs, four bars of that étude tired me out more than three run-throughs of a Bach Bourrée. Though I knew Anna wouldn’t want me to strain myself, I was determined to give her full-bodied translations of these pieces that contained lifetimes of emotion.

But I was so tired.

The author’s keyboard setup.

Ellen Li / The Daily Princetonian

“Hi, Sergey, how are you?”

“Hi Ellen, everything’s good here. Really hot though. How are you?”

“Um, good and bad.”

“Oh, what happened?”

“I saw my piano teacher, I love her. But I’m sick.”

“Oh no, you have COVID?”

“No, sick in brain. I, tired, head hurts.”

“Do you have ‘migraines’?”

“Yes, but, blood on brain? I need — how to say ‘radiation,’ ‘surgery’? In two weeks.”

A few Google-translations later, he got the picture, and taught me the words for “stroke” and “tumor.”

“I’ll pray for you. You know, I believe God hears my prayers,” he said, and after a few moments of silence, asked, “Will I see you again?”

I did see him again, one more time.

“Did I tell you I play guitar?” he asked, in English. “Have I played for you? This song is famous, maybe you will know.”

He told me to wait a minute as he got out his guitar, apologizing in advance; it had been a while since he played. After a few strums, he seemed to notice that the guitar was a little out of tune. But he played on, singing “Gorod Kotorogo Nyet.”

I caught a few words. Rain, snow, life. My brain was frazzled by the unfamiliar grammar of the title and refrain — city, of which there is none? — so I gave up on understanding, letting the minor chords wash over me. I applauded and thanked him as earnestly as I could manage without bursting into tears. He seemed embarrassed. We practiced the dative case.

“Okay Ellen, I have to go, I have another lesson. I had ten today,” he said, as the end of the hour approached. “I hope you will be okay. ‘Nye perezhivay,’ I think you will be okay. In America, the doctors are so good.”

He reminded me to cancel future lessons and we exchanged smiling goodbyes.

***

One night, a week before my operation, I am alone in bed. I have smuggled a pack of room temperature Heineken from the basement, because I’m a fucking adult. I ignore doctors’ warnings about drug-alcohol interactions, and Anna, who urges me not to take after drunk Russian poets.

I blast Rach 2 on YouTube. I read the top comments. They’re about dying.

Next, I look up the song “Gorod Kotorogo Nyet” (The City That Doesn’t Exist) by Igor Kornelyuk, which sounds nothing like Sergey’s hesitant acoustic performance over shaky internet. It’s a pop power-ballad, with a full orchestra, wailing electric guitar, and sincerity so raw it reminds me of ’90s Celine Dion, steeping me in nostalgia for the decade prior to my birth, the time Nabokov would call my “prenatal abyss,” the “twin” of the abyss I’m heading for. A world which, without me, is full of color, and almost the same.

The song ends. I play it again.

Night and silence for a century

Rain, or maybe snow, falls

It’s all the same, warmed by endless hope

I see in the distance a city that doesn’t exist

Where wanderers find shelter easily

Where surely they remember and wait

Day after day, I lose or confuse my path

As I head for the city that doesn’t exist

Who will answer me about my fate

Let it stay unknown

Maybe beyond the barricade of wasted years

I’ll find the city that doesn’t exist

There, a hearth burns for me

Like a monument to forgotten truths

I’ve made it to the last step

And this step is longer than life

I’ve made it to the last step

And this step is longer than life

Now, I realize that through learning Russian, I have been rehearsing my reincarnation, learning the world, building a self, from scratch. I am seizing back an illusion of control for all the times my illness has splintered my ability to read and speak, for those deaths I have lived, and re-emerged from no longer fluent in any language.

It’s not that I truly expect to die or have a stroke soon, though there is a small chance that I could. I just can’t shake the acute awareness of the fact that this consciousness will one day fracture. Perhaps suddenly, or perhaps after a long, laborious decline. I used to want to be a journalist or go to graduate school, but these aspirations now feel flimsy and unreal.

Even if I knew I had little time left, I don’t think I’d live much differently than I do now. I’d still have to rest a lot and wait out painful hours in bed. I’d play the electric keyboard by my bedside, running through Bach on endless repeat, neglecting to practice at a lower tempo. I’d still be reading a shameful volume of “Yuri!!! On Ice” fanfiction, making my way through 20-plus adaptations of “The Twelve Chairs” with Zoom watch-party buddies, working occasionally as an overpaid tutor in math and English. I’d probably be drilling Russian verb conjugations when my mind is too dead for anything else. And for what?

For the poetry I’ll never get to read. For the cities, like St. Petersburg and Almaty, that exist for me only in dreams. For the friends I promise, dishonestly, to see again soon. The gift of other people’s literature and time, that I might choose to call love. The love I hurl back through faulty translation.

For a quiet stroll down this ancient road. For every step, including the last, longer than life.

Ellen Li is a member of the Class of 2023 from Millburn, N.J. majoring in Comparative Literature. She can be reached at ellenli@princeton.edu. Li is a former Features editor for the ‘Prince.’