I’ve always had a morbid obsession with the aestheticization of my own reality. In my mind, if I existed within the realms of the aesthetic — if my room was beautiful, if my clothes looked good on me, if my hair fell in just the right way — I would be happy. I aspired towards the Platonic ideal of “that girl” for the longest time.

I hate to admit it, but I used to tell people I was without a doubt a New York City girl. Growing up on the other side of the world and coming to know America through the glittery lens of movies, New York represented everything that I wanted my world to look like — the lights, the hustle, the glamor.

I remember the first time I stepped foot in New York City. After squeezing through the ebb and flow of people in Penn Station, the stairs opened up to cool air, taxis blurring past, and an impossibly blue sky. Holding in my excitement, I felt a feeling of familiarity wash over me — I’d saved this exact image on a Pinterest board years back, manifesting the day I would see New York with my own eyes.

And now that I finally had, I allowed myself to feel a momentary sense of accomplishment (past me would have been so proud!) that quickly dissipated into the crowds of intimidatingly stylish people with places to be. This goal had become a checkbox I’d mentally ticked off before moving onto a new set of more precisely curated obsessions that would transform myself into the type of person I so desperately wanted to become.

Then, the other day, I was casually scrolling through TikTok when I stumbled upon an essay that kind of rocked my world. Rayne Fisher-Quann meditates upon “types” of girls, and how women online — and increasingly on TikTok — categorize themselves by a series of tropes as a Frankenstein-ified identity of sorts.

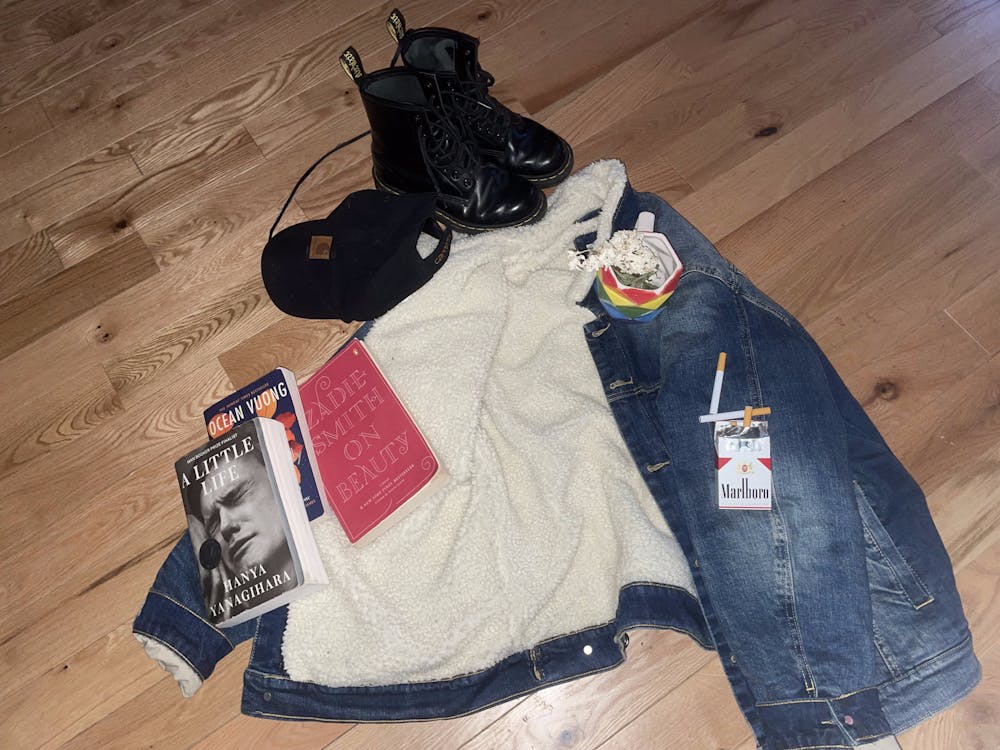

As Fisher-Quann writes, they “express their identities through an artfully curated list of the things they consume, or aspire to consume — and because young women are conditioned to believe that their identities are defined almost entirely by their neuroses, these roundups of cultural trends and authors du jour often implicitly serve to chicly signal one’s mental illnesses to the public.” You have your self-described “joan didion/eve babitz/marlboro reds/straight-cut levis/fleabag girl”; your “babydoll dress/sylvia plath/red scare/miu miu/lana del rey girl”; your “green juice/claw clip/emma chamberlain/yoga mat/podcast girl”.

Fisher-Quann argues that these categories exist to make women more digestible, easier to consume. She meanders on the thought that women exist to be commodified — that we exist to be perceived — and that we play into this assertion. She writes: “your existence as a Type of Girl has almost nothing to do with whether you actually read joan didion or wear miu miu, and everything to do with whether you want to be seen as the type of person who would.”

But then I realized, why does this matter? Why does Fisher-Quann insist that this is some kind of unexpected revelation, as if we aren’t all commodifying ourselves at every minute regardless of who we are?

Especially in a society that hinges itself on celebrity, does it matter whether I associate myself with Didion because I enjoy reading Didion, or whether I associate myself with Didion because I perceive myself as a girl who would read Didion?

Don’t get me wrong — Fisher-Quann’s take is an important one in terms of understanding how our identities are shaped and how we are perceived in this capitalist society. But it lacks compassion, the possibility that women can exist for themselves and still coexist with these categories of identities, and that these categories can help us inform how we move through the world.

I think we need to show ourselves more compassion. A few months ago, I cringed and criticized my younger self for striving towards any “type” of girl, for self-commodifying in this way, without noticing that it made it easier for me to exist and understand myself.

This demarcation of women into tropes initially reminded me of the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy — how, to Freud, women are viewed as either pure or promiscuous, either Madonna or Whore.

I am living in a patriarchal world where people believe that femininity precludes complexity. I grew up trying to distance myself from the feminine as much as possible, striving to adhere to masculine tropes and traits in an attempt to make myself worth something. I held the belief that I could not be worth anything without appearing as a man in a man’s world. I held the belief that femininity was weakness — that I could only be either Madonna or Whore, and that there was no in between.

Which is why, to me, these character tropes are a way of reclaiming femininity in a form that isn’t merely sexual but multidimensional. Being a “joan didion/eve babitz/marlboro reds/straight-cut levis/fleabag girl” allows me to escape narratives built by men for women, to construct our own narratives and categories to fit within. To me, this is a form of feminist rebellion, of escape.

So yes — I am a New York City girl. I am in my Didion-Girl-Reading-In-Firestone-Overalls-Baseball-Cap-Wearing-Era. I am both Madonna and Whore, and I am everything in between.

Steph Chen is a Contributing Writer for The Prospect and Data at the ‘Prince.’ They can be reached at stephchen@princeton.edu.

Self essays at The Prospect give our writers and guest contributors the opportunity to share their perspectives. This essay reflects the views and lived experiences of the author. If you would like to submit a Self essay, contact us at prospect@dailyprincetonian.com.