“Signatures,” a two-part senior thesis show by Megan Pai ’22, mobilizes the audience not just as spectators, but as performers and collaborators.

Modeled after the structure of a music concert, the show consists of two halves, beginning in the Hurley Gallery in the Arts Tower of the Lewis Center for the Arts and concluding in the Hagan Gallery at 185 Nassau Street. In lieu of museum placards, letterpress-printed programs stationed at the entry include a list of pieces to be “performed” (by you, the viewer). Visitors are encouraged to take one of the “invitations” scattered near the entrances of the galleries — silver in the Hurley Gallery and gold in the Hagan Gallery — and leave the card in the other gallery upon exiting. As the writing on the cards suggest, the show’s “Intermission” lasts for the duration of time the visitor spends traveling between the two parts of the show. Over time, the exchange of gold and silver between the two spaces provides a spectral record of those who have chosen to participate.

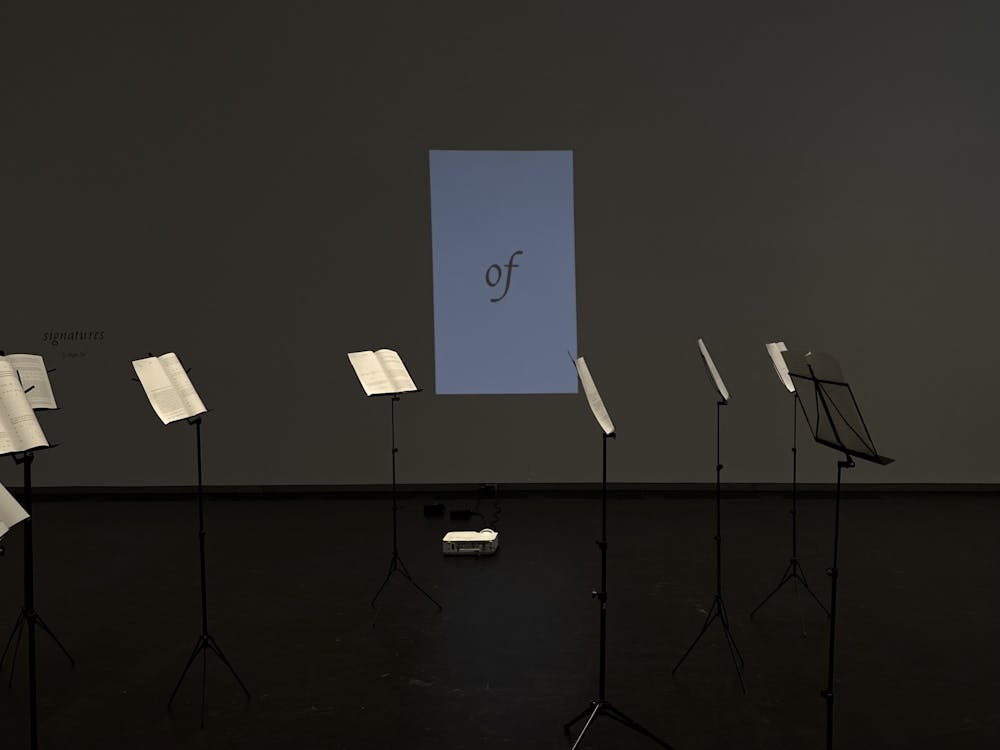

Wall text prompts the reader to circulate through the Hurley Gallery clockwise around the perimeter of the room, engaging with text as both book and video, before ending in the center of the space, where a troupe of unmanned music stands wait patiently for “performers” to take their places. Music by Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky — raw, unedited recordings of Pai practicing piano — softly rumbles in the background of the gallery. In the Hagan Gallery, a single video projection cycles through all the works on display in the Hurley Gallery, set to Chopin’s “Fantaisie Impromptu.” The video and audio are synced between the two galleries —when music plays in one, the other falls silent.

Calling upon the audience to actively read and parse through the works with their hands, “Signatures” shatters the formalities of “the white cube” — a gallery aesthetic associated with modern art, and characterized by its white walls, rectilinear form, and bright overhead lighting. The design of the white cube prompts audiences to maintain a safe distance from the art object — both to protect the artwork and also to allow for a more seamless experience in the gallery. This sterilized experience of visual art often relies on making the processes of production and consumption invisible, in veneration of the final product.

Through this fetishization of the art object, we become fixated on its physicality, while remaining oblivious to the manual labor of both making and perceiving. The hermetic setting of the gallery is meant to elevate our visual experience of the art itself by creating a utopian space that exists beyond the banal of the everyday. According to literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky, the role of art is to reanimate life for us through a process of defamiliarization. For Shklovsky, the poetic or painterly image does not simply represent the object, but instead, introduces a new way of seeing.

But in “Signatures,” Pai seems to defamiliarize the process of reading itself. Reading is a two-part process that involves first decoding the sign — a word or image — and then comprehending the sign within its context. Within the show, we can still decode words and images as individual units. Yet the insertion of physical disruptions, or “glitches,” in the infrastructure of the text makes contextual comprehension difficult, stymieing our ability to form links between words —sometimes even between syllables of words. As a result, we become aware of reading not just as a cognitive process, but also something that is distinctly physical.

Courtesy of Megan Pai / Credit to Chris Reade

Each of the pieces in “Signatures” presents its own method of systematized abstraction or obstruction that complicates our ability to slide between the two stages of reading. In some pieces, such as “Sight Reading” and “Notes from Rinna,” the text itself is fragmented into chunks, making it difficult for us to place the words or phrases within their respective contexts, while other pieces present physical glitches to confuse our reading. In “Muscle Memory,” for instance, the transparency of the paper causes the images and the text to bleed from page to page, muddying the legibility of the sign. And in “Transcription,” the imperfections and idiosyncrasies of Pai’s handwriting similarly slow down our reading of the text. At times, there even seems to be synchronicity between the stylistic glitches in the videos and the music in the gallery, as Pai stops and starts in her practicing, creating an experience of sonic synesthesia.

While walking through the show, I thought of a neuroplasticity experiment in which the human subject wears goggles that turn their vision upside down. Although the subject initially struggles to navigate through space with their upside down vision, they eventually become acclimated to their new experience of perception — so much so, that once they take off their goggles and return to their normal vision, they are spatially confused and have to readjust once more.

Each piece in “Signatures” seems to present its own pair of reading goggles that distort the cognitive process by which an image or text is transformed into something filled with meaning. With each physical step we take through the gallery, we are forced to take a few mental steps back and relearn to read in the system Pai has set up for us. These works purposefully ask us to slow down and take care with our looking. Sometimes, this may feel frustrating, as the meaning which feels as though it should be accessible is just out of our reach. Yet, as with any great work of art, I have found that the work rewards you the more time you spend with it.

Cameron Lee is a Head Editor Emerita of The Prospect. She also writes about modern and contemporary art, pop culture, film, and Asian (American) identity, and can be reached at cameronl@princeton.edu, or on Instagram at @camelizabethlee.