I recently asked my roommate about her experience in a tap dance class at Princeton. I was completely unfamiliar with the dance program and was curious to learn about the class structure and format. As our discussion unfolded, I learned that the University, understandably, reimbursed the cost of dance shoes for this class, which hovers around $100. Such reimbursement is important for many reasons: it encourages students to try dance classes by eliminating the burden of cost for participation, and it ensures that all students are given an equal chance — at least based on equipment — to perform well in the class. I was glad to see a system in place that works to foster an environment where all students are able to experiment and take advantage of the opportunities around them.

However, hearing about this setup within the dance department made me reflect on my own experience in different departments where, although particular shoes are not necessary for participation and engagement, other materials — most often books — are required. While books and shoes are not the exact same in terms of their role in students’ ability to participate in class, their importance in their respective courses is not markedly different. The University should fully subsidize all required course books to eliminate obstacles to exploring a class.

On syllabi, books are often labeled as “required,” implying that you must buy them; should you not, you may not be able to participate in class, write discussion posts, or understand the lecture. Thus, without purchasing the necessary texts for a course, a student’s performance can easily suffer. In this regard, there seems to be a closer connection between the imperative need for both dance shoes and books in order to perform adequately in class.

With this in mind, it seems puzzling that the University grasps the importance of dance shoes, motivating them to reimburse students for them, yet does not have a similar policy in place regarding course books. While the price of any individual book usually remains below that of a pair of tap shoes, they can quickly add up, especially when you are buying several of them for each class every semester, including some pricey textbooks or niche academic literature. Although this cost can prove burdensome, the cost of lacking certain texts is also rather significant, leaving many students with a difficult choice.

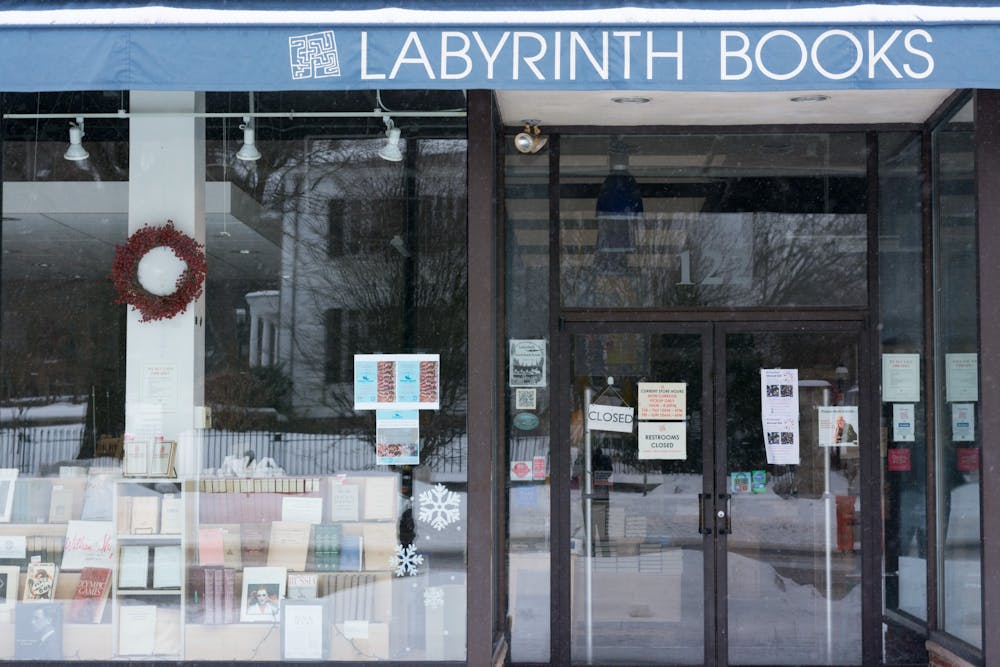

Understandably, the University has a finite budget and cannot pay for everything students may possibly need during their four years on campus. Yet books play an integral role in one’s college career: they open our minds up to new ideas, teach us about fascinating subject matters, and allow us to meaningfully engage with the courses we take. It seems to me that should the University decide to be generous in any particular regard, course books may be a good place to start. While books are meant to be included in some financial aid awards, these awards are often not enough. To ensure that the high cost of books does not become an unduly heavy burden on students, a more appropriate policy may be to pay for books directly rather than through financial aid grants. Setting up a system where the University pays for books at Labyrinth rather than students would help to avoid situations where students are unable to afford their books using just financial aid grants.

Don’t get me wrong: I certainly enjoy the decadent brunch spread at Forbes College on Sundays and I love receiving free Princeton apparel. However, I see greater value in reallocating funds so that students do not feel the need to either download books as PDFs, buy used texts with others’ notes in the margins, or forgo buying certain books altogether in order to avoid the exorbitant cost of books. It seems rather intuitive that books are a necessary part of a college student’s experience, so making them more affordable would only promote the goals and expectations of college students that have already been established.

Ava Milberg is a sophomore from New York City. She can be reached at amilberg@princeton.edu.