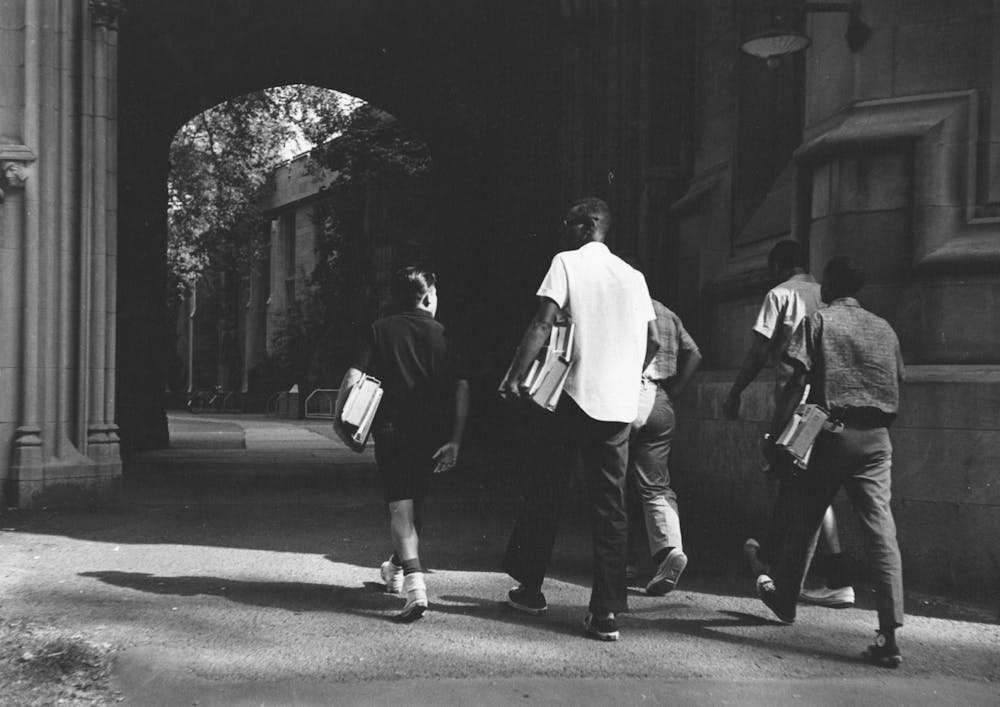

While searching the archives of Mudd Library, Professor of History Alison Isenberg found a “beautiful, hand-created” photo album. The work inside, captured by documentary photographer Sol Libsohn, highlights a key moment in the University’s contentious history surrounding racial integration: the 1964 Princeton Summer Studies Program (PSSP). The program invited 40 public high school students — 30 of whom were Black — to reside on campus and attend classes at the University.

Drawing from Libsohn’s collection, a small group of undergraduate curators designed a photo exhibit, which is now on display in Wilcox Hall of First College. Titled “First on Film: Creating Spaces for Racial Reckoning on Campus, 1960s and Now,” the curators looked to connect the legacy of PSSP — and First College, where it was based — to racial inclusion and student activism today.

The exhibition serves as a final opportunity recognize this legacy. First College is set to be demolished this summer and replaced by Hobson College in 2026. The gift of Mellody Hobson and the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, the University’s eighth residential college will be the first to be named for a Black woman.

The campus landscape is changing — both physically, with the destruction of First College, the construction of Hobson College, and socially in response to student protest. The “First on Film” exhibit emphasizes the successes and failures of Princeton’s efforts for racial inclusion and their implications for the present.

“[That] summer was not just an isolated event,” curator Gil Joseph ’25 said. “We are trying to show the long journey of Princeton coming to terms with its relationship with race, and how it has been an ongoing battle.”

Isenberg and documentary filmmaker Purcell Carson, who worked to locate the rest of Libson’s collection, have researched PSSP as part of their collaborative work on Trenton, NJ. For years, they wanted to engage Princeton students in a public history project and were ultimately able to do so with the support of Head of First College AnneMarie Luijendijk as well as the College’s Director of Studies Johanna Rossi Wagner.

“The photos took on a new life and gained a new meaning through the interpretations that the students brought,” Carson said.

In 1964, PSSP immersed high school juniors in college-level academics with the goal of increasing applications from Black students. In the previous academic year, only 12 Black undergraduates attended the University.

Several PSSP graduates who ultimately attended Princeton said in interviews with Carson and Isenberg that they felt misled — their experience in that summer led them to believe the University was racially integrated, which was far from reality. In the fall of 1964, only 11 Black students entered in the first-year class.

However, the program’s curriculum, featuring works by James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison, still engaged students in the national conversation around race and equality.

“They weren’t just high schoolers from New Jersey watching the civil rights movement happen from afar,” Carson said. “For the first time, they were being told to think of themselves as people who could make a difference.”

Beyond its influence on the students, PSSP had a lasting impact on the broader landscape of higher education, both at the University and nationally.

“The University was beginning to move toward racial integration and was on the cusp of coeducation. And this summer program was an important piece of that puzzle. The program served an important role in engaging President Goheen in the fact of having black students on campus,” Isenberg said.

PSSP also became a model for the national Upward Bound program, which was established the following year.

Rather than trying to capture the program’s far-reaching implications, Libsohn’s photos document small moments: a student reading a book, hands clasped over his forehead. A son, carrying his suitcase, walking beside his father. A group gathered on couches, talking in front of Wilcox Hall’s geometric windows.

The photos, Joseph said, capture the summer in its “rawness.”

“For me, it was impactful to see the photos of Black teenagers just being on campus,” Joseph added, “not just studying, but also discussing, having fun, and creating art in the same places that we are in right now.”

During Wintersession, the curators — led by Julia Chaffers ’22, Emily Sanchez ’22, and Mohan Setty-Charity ’24 — collaboratively selected photos and designed the exhibit, covering walls in Lewis Library with print-outs in the process. They considered both the history they had learned from Isenberg and Carson as well as advice from Princeton University Art Museum curators, who helped them determine how to convey their message visually.

“We decided we didn't want to tell a narrative in any specific sense,” Chaffers said. “The exhibit falls more toward asking questions and starting a conversation.”

Chaffers is a senior columnist for the ‘Prince.’

To prompt personal reflection from viewers, the curators chose images that are relatable due to their recognizable backgrounds, like Nassau Hall.

“Images allow for more subjective responses,” Joseph said. “As people are walking through the exhibit, they could be thinking about their own journeys as current Princeton students or alumni and their experience in a place that is still a predominantly white institution.”

In an explicit connection to the present, the exhibit culminates in a display of photos from recent protests on campus — such as the 2019 demonstration at the “Double Sights” monument — that have called on the University community to confront racism.

“We’re showing this continuity of Black students at Princeton trying to create space for themselves,” Chaffers said.

The significance of the exhibit is compounded by its location in First College, which has been central to the University’s complex history of racial integration.

In response to undergraduates’ growing opposition to eating clubs for their exclusivity, an opt-in community called the Woodrow Wilson Lodge was formed in the late 1950s. The Wilson Lodge became the University’s original residential college, Wilson College, in 1967.

“It was an important alternative to the eating clubs and offered a more egalitarian, democratized living situation,” Carson said. “It has strong ties to the struggles for inclusion and racial justice on campus.”

Wilson College later became the center of controversy over the legacy of its namesake. After five years of student activism, the University removed the name of President Woodrow Wilson, Class of 1879, from the residential college and the School of Public & International Affairs.

In light of this history, Sanchez said, “The exhibit is a way to reclaim the space for the students and remember it in ways it might not have been before.”

“It’s very important that we do not just destroy First College and move forward,” Joseph said. “How do we take away the lessons we learned from its existence?”

Molly Taylor is a Features contributor for the Daily Princetonian. She can be reached at mollypt@princeton.edu.