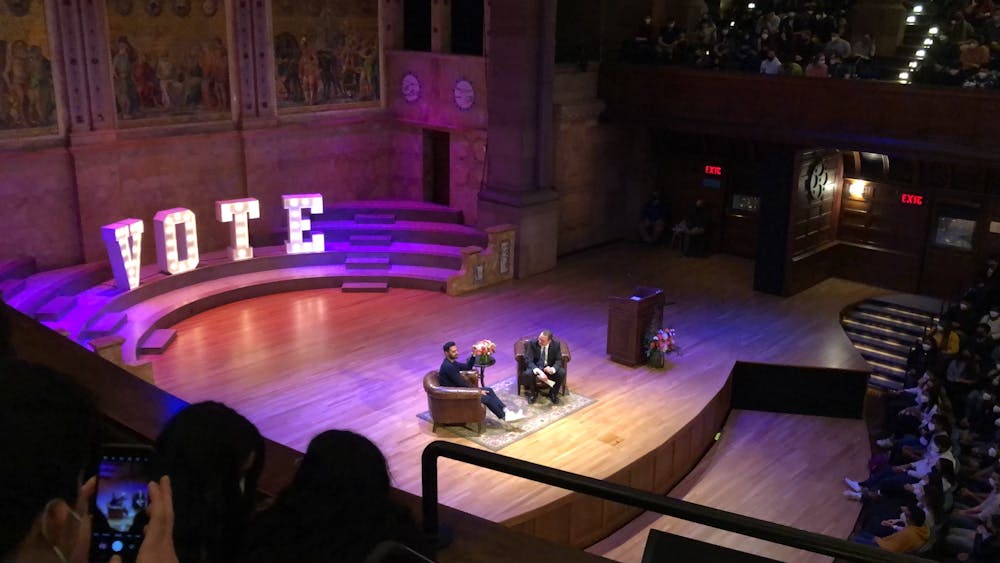

A student asked Hasan Minhaj, at a Vote100-sponsored event in Richardson Auditorium on Tuesday, about the way caste affects South Asian immigrants in the United States, especially in California. My first thought was that he probably wasn’t qualified to answer. I thought that, being a second-generation immigrant like me, he probably doesn’t have too much familiarity with the caste system, but I wanted to hear what he had to say.

In his response, Minhaj called the caste system and Indo-Pakistani conflict a thing of the 1940s and 50s. Speaking primarily to the Desi contingent of the audience, he asked, when there’s a cricket game going on between India and Pakistan, have you ever noticed that it’s not really about the game? “The game is boring,” he said. Putting on a stereotypically South Asian accent, he shouted, “India! Pakistan!” ostensibly representing the supposed two sides of the divide. He said that if that is what we are concerned with, the British have won.

This made plain that he is not speaking for an audience from South Asia or deeply ingrained in South Asian culture. I wouldn’t say I’m either of those things particularly — though I’m working on connecting with a cultural tradition that my Indian (born and raised) parents and their families have been a part of for as long as anyone can trace back.

I know that my place at Princeton exists partially due to caste privilege. Both my parents are from higher castes. Although caste-based discrimination is illegal, it does still occur both formally and informally.

I shouldn’t have to tell you that caste-based discrimination is real, and it’s not true that it only popped up when the British colonial project began or that it went away when they “left” in the midst of Partition. Of course, British rule exacerbated social antagonisms and codified caste in certain forms of law, but it would be a mistake to say that caste is a thing of the past.

When my parents asked my grandparents for their blessing to get married, the difference in their castes was certainly a topic of discussion. Members of the Dalit caste are still often untouched. Quotas for historically marginalized groups in India are good, but they can’t do the work of reimagining or abolishing social orders. There is no doubt in my mind that if my parents had come from lower castes, it would have been more difficult for them to work in scientific research and pharmaceutical regulation in the United States — and for me to be here.

Saying that engaging in Indo-Pakistani rivalry is evidence of “the British winning” erases experiences like my grandfather’s. In 1947, when the new border between India and Pakistan ran through his home state of Punjab, he had to pick up and move to what was a new nation-state. Plus, we should acknowledge that athletic competition is one of the safer ways for this real geopolitical and interpersonal divide to manifest.

We have to face the fact that Hasan Minhaj, at least as displayed at this week’s Vote100 event, is not for people like me. It only takes a cursory glance at Vote100 publicity to know that it is an overwhelmingly white space.

When I was a Class of 2024 ambassador for Vote100 last year, I found the same to be true. As a small group of dedicated first-years, the other ambassadors and I laid out plans to revolutionize the initiative and have it truly make a difference. For a lot of reasons, our intended plans didn’t pan out.

Voting is cool, but I am skeptical as to how much a University initiative can do to change people’s minds about not participating. The 100 percent student participation in civic engagement is perhaps a noble goal, but with Vote100 itself reporting that Princeton students voted at a rate of 75.4 percent in 2020, I have to say: that might just be good enough.

Now, I have more important things to worry about — I find my energy devoted to organizing with the Pride Alliance and South Asian Progressive Alliance, for example.

When Vote100’s endorsement message and Kevin Kruse’s questions about voting kicked off the event, the indifference in the audience was palpable. Students showed up for Hasan Minhaj: comedian — not Hasan Minhaj: man who might convince me to vote, let’s hear what he has to say.

I really deeply value representation as much as the next guy, so although I am not the biggest fan of Minhaj anymore, I had to go. Watching his comedy special “Homecoming King” five years ago was exhilarating; it seemed to tell the truth about a brown kid’s life in America. The closest I had gotten at that point was Disney Channel, but Ravi on “Jessie” and Baljeet on “Phineas and Ferb” were caricatures and rarely anything more.

But Minhaj the comedian does not represent me. Being a second-generation Indian immigrant doesn’t have to mean letting everything Indian go. In fact, our lives are inextricable from the past, present, and future of that subcontinent, currently the home of a billion and a half breathing people. With them, I hold my breath.

Mollika Jai Singh is a contributing writer for The Prospect at the 'Prince.' They are also a co-Director for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging and an Associate Opinion Editor. To talk anything ‘Prince’-related or otherwise, say hi @mollikajaisingh on social or at mjsingh@princeton.edu. This piece reflects the author’s views alone.

Self essays at The Prospect give our writers and guest contributors the opportunity to share their perspectives. This essay reflects the views and lived experiences of the author. If you would like to submit a Self essay, contact us at prospect@dailyprincetonian.com.