On Feb. 9, Molecular Biology professor and department chair Bonnie Bassler was awarded the 2022 Wolf Prize in Chemistry.

The $100,000 award is given annually by the Wolf Foundation in Israel to scientists and artists “for their achievements in the interest of mankind and friendly relations amongst peoples.” The scientific categories of the prize include agriculture, chemistry, mathematics, medicine, and physics. The chemistry prize is often considered to be the most prestigious in the field, after the Nobel Prize.

Bassler, who also serves as an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, was awarded the prize along with Carolyn Bertozzi of Stanford University and Benjamin F. Cravatt III of the Scripps Research Institute. They were honored for their “seminal contributions to understanding the chemistry of cellular communication” and for creating new methods to study these processes.

Bassler and Bertozzi are the second and third women ever to receive the chemistry prize since its establishment in 1978. The first was Ada Yonath of the Weizmann Institute of Science, who won in 2006 for her research on the structure and function of ribosomes. Yonath later went on to receive the 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

“I’m delighted to receive the Wolf Prize this year,” Bassler said in an interview with The Daily Princetonian. “[It] was a big surprise to me because I’m not a chemist, but I certainly do biology to understand the chemistry that bacteria communicate with. It was a delight to win in chemistry, because it meant that that aspect of our work was being recognized.”

Bassler’s team focuses primarily on communication among bacteria and how group behavior evolved from bacteria earlier in our planet’s history.

“What my team wants to understand,” she said, “is how bacteria can give us life or kill us, despite being so tiny.”

To do this, Bassler’s team studies how bacterial organisms communicate with each other through chemicals and then act in groups to carry out tasks that they could not accomplish as individual organisms, a communication strategy known as quorum sensing.

Quorum sensing occurs when bacteria grow and divide through binary fission: one cell becomes two, which becomes four, which becomes eight. As cells divide, they produce and release small molecules called autoinducers, which are akin to hormones. As the cells grow and divide, more and more molecules are created.

When the autoinducer numbers reach a particular threshold, they are detected by bacteria, which sense that there must be neighboring bacterial organisms nearby. In response, the bacteria act in unison to change their gene expression. (Despite this complex event, the bacteria are not truly “aware” of how many cells are around — they simply measure the concentration of these chemicals as a proxy for cell number.)

“We know that [quorum sensing] is true now, because we've discovered the molecules that are involved,” Bassler said. “In fact, we can make the molecules synthetically and just squirt them on individual cells, and they'll do all the tricks. They really use the molecules to know if there are other cells around them.”

The behaviors of groups of bacteria help determine certain biological traits. One such trait is virulence, defined by biologists as the degree of damage caused by a microbe to the host. A bacterium with a low degree of virulence starts releasing toxins as soon as it enters the human body, which is often an ineffective strategy, because the human immune system will be able to immediately detect the bacterium and destroy it.

Alternatively, some bacteria have evolved to wait to release toxins after entering the body, so that they may reproduce and spread undetected. At the right moment, all the bacteria release their toxins together, allowing them to overpower the host’s immune system. Bassler’s ongoing research on quorum sensing has practical applications in medicine by preventing this second strategy.

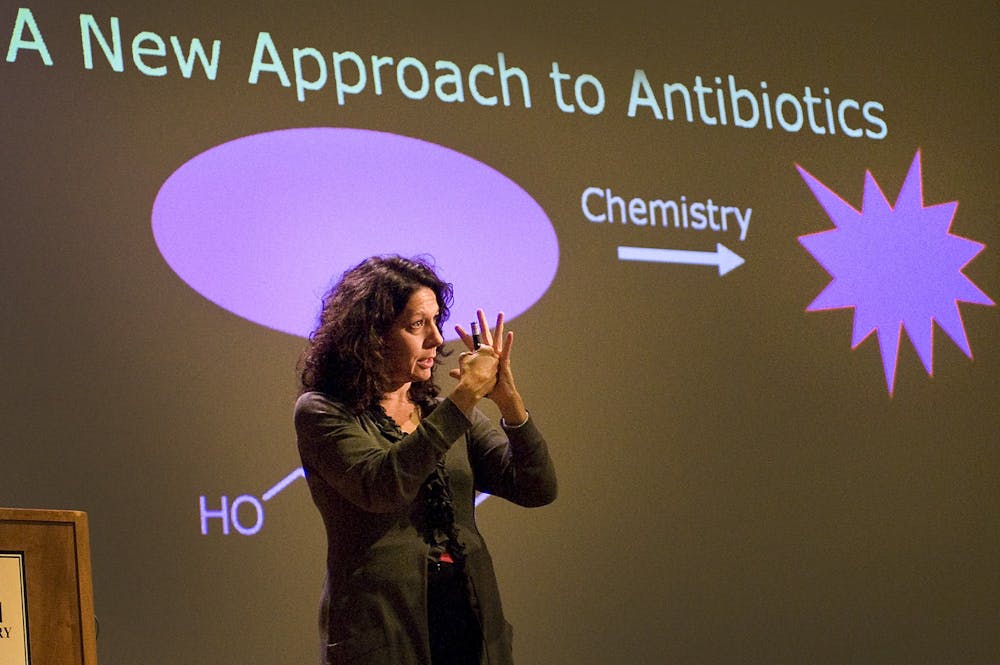

“If you can make bacteria that can't talk or can't hear, employing strategies to interrupt communication, you can have new kinds of medicines,” Bassler said. “And that’s what we’re doing right now.”

Despite her success in the field, Bassler’s career path to becoming a molecular biologist was not linear. At the start of her undergraduate studies at the University of California, Davis, Bassler planned to become a veterinarian. Instead, she became interested in Molecular Biology — and specifically bacteria — after joining the lab of Fredric Troy. Near the end of her graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, Bassler attended a talk by Michael Silverman during which she became “mesmerized” by how certain bacteria with bioluminescent traits act as a group to emit light.

Following her transition from graduate student to full-time researcher, Bassler’s years of working in the field have not been without hurdles. At the start of her career, most people did not believe bacteria could communicate or exhibit group behaviors, considered “higher organism traits.” Once that idea became accepted, others challenged her assertion that bacterial communication could be considered language.

“This idea received a lot of skepticism,” Bassler said, “which slowed us down, but eventually others started to recognize our work.”

In her interview with the ‘Prince,’ Bassler spoke highly of her research team.

“What is most significant to me about winning [the Wolf Prize] is that it is an amazing validation of the creativity, ingenuity, and tenacity of my gang,” Bassler said. “I am very proud of and happy with my group.”

Bassler’s students echoed a similar sentiment.

“Bonnie is a fantastic mentor. She just cares so much,” said Isabelle Taylor, a postdoctoral fellow at Bassler’s lab.

“I think every person I’ve worked with has cared very deeply about the science that I’ve worked on. But Bonnie doesn’t only care about the science, she cares about the people doing the science as well. That's apparent in everything she does, and every interaction I have with her. She wants me to be the best person and scientist I possibly can be,” Taylor added.

Taylor also reflected on her time spent as a woman in a lab led by a female professor.

“I’ve always worked for men and they’ve been great mentors, and I just never thought that there was anything that would be particularly different about working for a woman,” Taylor said. “Now, after having done my postdoc, I think Bonnie’s been able to lead by such a wonderful example in her lab... I feel empowered.”

“When she won the prize, the first thing she said to all of us was, this is your prize,” Taylor added. “In fact, she wins prizes pretty frequently. And that's always what she says.”

Mahya Fazel-Zarandi is a staff writer for the ‘Prince.’ She can be reached by email at mahyaf@princeton.edu or on Twitter @MahyaFazel.