Jadwin Hall, the blockish brick behemoth on Washington Road, has been home to the Princeton math and physics departments since 1970. While the building itself underwent renovations as part of Princeton’s sustainability plan, Jadwin still embodies the remnants of an older worldview that has characterized STEM culture at Princeton since Albert Einstein’s time as a lecturer in 1921.

Every day as I walk to my math class on the building’s A-level floor, I pass a wall commemorating University-affiliated Nobel Prize laureates of STEM fields, hung up in photo frames. All are men, and very few laureates are identifiable as persons of color. Just adjacent, another hallway has a sparse collection of portraits of important female scientists, most of whom belong to ethnic minorities. If buildings carry the story of their inhabitants, I can’t help but wonder what Jadwin intimates to STEM students traversing its hallways?

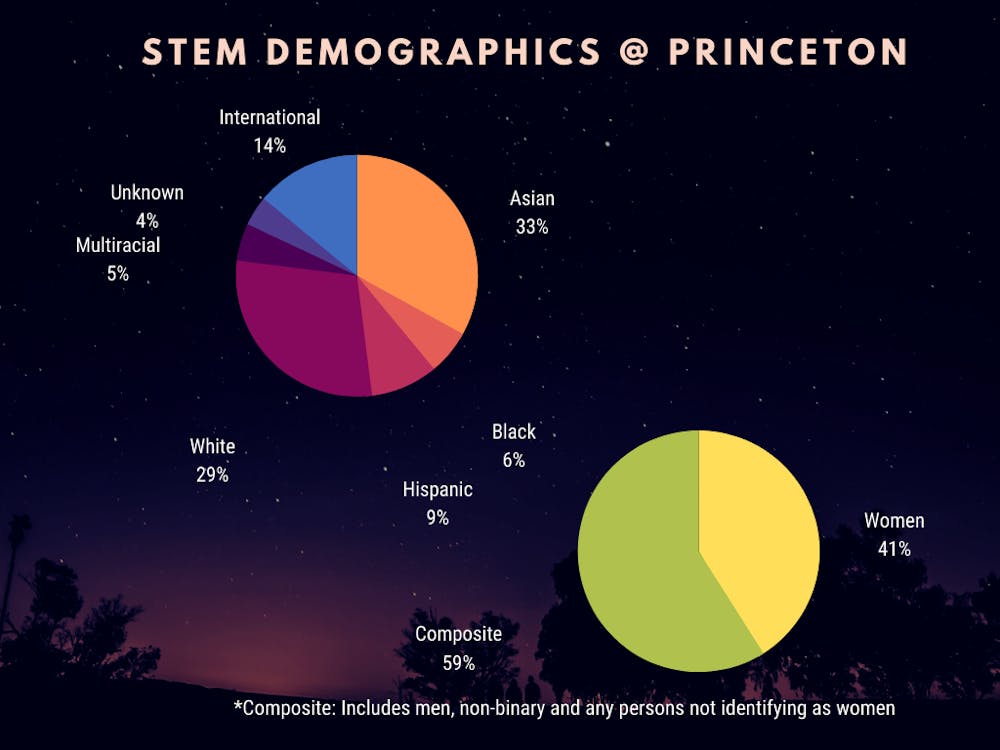

While my observations about Jadwin could be a retrospective viewpoint, it’s undeniable that Princeton’s STEM culture must undergo major changes to improve the inclusion and involvement of students facing different hurdles to entering STEM pathways. When examining recent data collected on the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s “Diversity Dashboard,” I found that only 41 percent of B.S.E. students are women compared to 50 percent of undergraduates on campus. In the context of ethnic demographics, it’s even more alarming that only six percent and nine percent of engineering undergraduates identify as Black and Hispanic, respectively. These gaps in student representation are symptomatic of how the structure of STEM education at Princeton perpetuates systemic barriers to opportunity.

Based on undergraduate data from Princeton Engineering Diversity Dashboard

Laya Reddy / The Daily Princetonian

Prerequisite classes, pillars of our STEM curriculum, have come under fire for creating barriers to entry. Columnist Abigail Rabieh speaks to the struggle of humanities students being turned away from further exploration, and Community Opinion Editor Rohit Narayanan encourages STEM departments to reduce their prerequisite requirements to encourage more non-STEM concentrators. While I agree that the prerequisite STEM classes are significant obstacles to many students, they are far from the only barriers underrepresented and underprepared students face. By reforming the curriculum to better support and include these students, introductory classes could become express lanes into STEM fields.

There’s an important and often overlooked trend centered around the preparation gap and how it carries forward to pursuing STEM in college. Even though the large lecture size and lack of resources in introductory courses aren’t particularly beneficial to advancing a student’s learning, these flaws, more importantly, exacerbate pre-existing educational inequity. High school students receive differing levels of academic support — such as tutoring — and differing access to advanced course offerings before they matriculate at Princeton. Under-preparation can become an obstacle in choosing their path over the next four years.

Data from The Daily Princetonian’s fall Frosh Survey finds that students coming into Princeton having taken at most pre-calculus had only a 6.1 percent chance of matriculating into engineering. That probability skyrocketed to 41.6 percent for students who took multivariable calculus or linear algebra in high school. This correlation shows that lower levels of academic preparation in math before college decrease students’ likelihood of breaking into STEM disciplines in the first place. Even with the aid of the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning and professors’ office hours, introductory courses with lecture halls at full capacity don’t incentivize interested students to embrace a STEM track moving forward.

This is not to say that there aren’t some merits to Princeton’s STEM curriculum. When I interviewed Andres Larrieu ’23 about his first semester majoring in B.S.E., Larrieu said, “It’s an unexpected positive. Especially coming in as a freshman, after spending time working hard together on problem sets, you just get to know people really well. It’s not something you really have to do in SPIA.” (Larrieu began his time at the University as B.S.E. but switched to A.B. and is now a SPIA concentrator.)

Whether it’s bonding with other students over challenging questions in a precept, or making friends as you grind out a problem set for an 11:59 p.m. deadline, STEM culture at Princeton demands intellectual collaboration to succeed. The issue is that students are collaborating to keep up with the high-stress curriculum rather than utilizing collaborative time to innovate.

Speaking from personal experience, co-creation environments in which everybody is a stakeholder and active participant in their education make people feel more included. Reworking the collaborative structure of precept as an opportunity to solve real-world problems and create new ideas could be a great jumping-off point for the STEM curriculum.

It’s easy to feel overlooked or left behind in fast-paced STEM classes. Allowing students to take more ownership of their education can lead to greater involvement and inclusion at Princeton. Implementing student-involved seminar classes and more team-led, project-based classes — such as those offered by the Keller Center — in introductory STEM courses would incentivize and retain more students interested in STEM than our current curriculum.

Roughly 37 percent of all degrees conferred to the great Class of 2020 fall into STEM fields. This rising interest in engineering and the sciences means that it’s more important than ever to shape an academic culture welcoming all who enter FitzRandolph Gate. As Larrieu told me, “You really can’t do Princeton alone.”

Laya Reddy is a first-year from Chicago, Ill. intending to concentrate in economics. She can be reached at lr3956@princeton.edu.