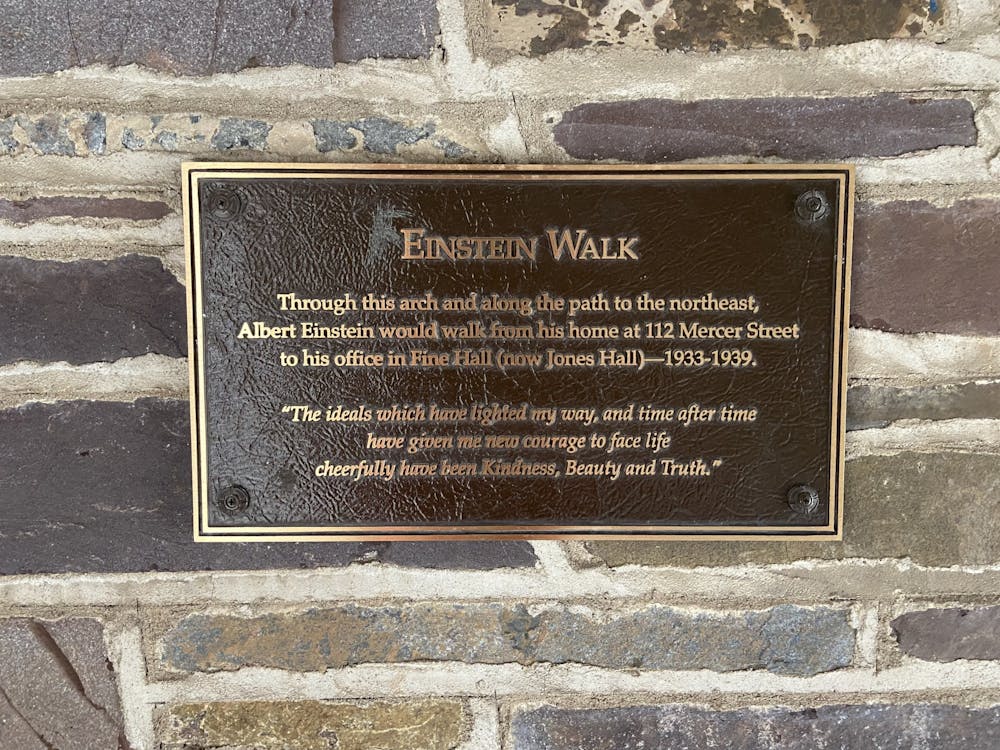

Each morning, whether I’m sprinting to my 8:30 a.m. Writing Seminar or strolling leisurely to my 10:00 a.m. lecture (I can assure you, the difference this hour-and-a-half makes is monumental), I cross through an arch known as “Einstein Walk.” I noticed this when I first moved in, but since then, the fading plaque has become just another peripheral blur on my morning sprints to class.

On weekends, when I get the chance to slow down a bit, I find that Einstein’s legacy has left its mark around town: Mercer Street, a mere five minutes away from the center of Princeton’s campus, was home to Albert Einstein from 1935 until his death in 1955. And in 2003, the Princeton Historical Society was the recipient of 65 pieces of Einstein’s furniture. Although never actually a member of the University’s faculty, Einstein called Princeton home for more than 20 years, contributing revolutionary work to the Institute for Advanced Study in an office in Fine Hall provided by the University.

These celebrations of Einstein and his time in Princeton are quite visible, displayed on street corners or carved on plaques. The most notable of these commemorations, though, was also probably the most discrete: Einstein found a home among wool sweaters and blue jeans. Starting in the early ’90s, tucked into the corner of Nassau Street and Dohm Alley, Landau’s — a clothing store that boasted “The World’s Most Beautiful Wool” — was once home to the only Albert Einstein Museum in the world. Past Princeton students and residents on the hunt for the perfect autumnal sweater would have stumbled upon various memorabilia and posters depicting the man who called Princeton home for the last years of his life — an important, if not slightly out of place, reminder of Einstein’s impact on both the University and the town.

Passed down through three generations of Landau family members, the store was most recently under the ownership of Henry and Robert, the grandsons of Henry Landau, the original owner. Prompted by the filming of “I.Q.” here in town, the brothers established the Einstein museum within their store. “I.Q.,” a 1994 romantic comedy starring Meg Ryan and Tim Robbins, tells the story of a Princeton graduate student who finds love, aided by her uncle, Albert Einstein — highlighting Einstein’s omnipresence in Princeton while also providing hope for lonely grad students everywhere.

In hopes of attracting actors and film crew to shop in the store, Landau’s asked their patrons to bring in 50’s-inspired clothing: “One lady brought in one Harris Tweed overcoat. So we went to Plan B, which was ‘Bring in your Einstein memorabilia.’ And that was like we opened up the floodgates,” said Robert Landau in a 2020 interview. Until its closing in 2020, the store served as a reminder of Einstein’s legacy, even finding its way into a 2017 Jeopardy Question: “Oddly the only museum devoted to this physicist is tucked inside a woolen shop in Princeton NJ.”

The town’s devotion to the great physicist is clear, whether evident through shiny plaques or memorabilia that stood among wool sweaters. Einstein’s legacy spills out beyond the town of Princeton, onto the campus as well. His style of thinking is a kind Princeton seems to celebrate — Frist Campus Center houses the “Einstein Classroom” — preserved through the building’s renovation. And after his death in 1955, the ‘Prince’ published two issues dedicated to celebrating his life. In Princeton, whether you're dashing to French class or searching for that perfect autumnal sweater, Einstein is by your side.

In May of 1921, Einstein took the stage in McCosh 50 with the goal of explaining the theory of relative motion to 400 onlookers (perhaps this fact will serve as inspiration the next time you’re struggling through an Economics exam in McCosh — Einstein could have sat right where you are sitting now). Just hours earlier, the University had given Einstein an honorary degree. He spoke in German, though the speech was then translated into English and delivered again orally by Princeton physics professor Edwin Adams. The speech was the first in a five part series of “Stafford Little Lectures.” Einstein would deliver these lectures across five consecutive days. By his third lecture, though, as his theories became more and more complex, the once vast crowd began to dwindle. His third lecture was held in a small classroom, a departure from McCosh 50, Princeton’s largest lecture hall.

As a prospective English major, whose goal (admittedly) is to make it through Princeton without ever coming near a problem set, I’m certain I, too, would’ve fled the room at the first mention of inertia. Perhaps surprisingly, though, even some of Einstein’s (non-English major) colleagues would’ve fled with me: by the time he gave these lectures in Princeton, much of his most famous work was behind him. As his work progressed and reached higher levels, his theories began to be incomprehensible even to his colleagues and peers, let alone a 400-person audience of non-mathematicians.

Still, Einstein’s ambitions helped earn him the plaques and commemorations sprinkled throughout the campus and town — it was his unwillingness to conform to standard ideas of thinking that helped open the door to his success. As someone who feels most at home — though also most confused — when surrounded by fantastical worlds, abstract narrative theory, and metaphysical ponderings, there’s something remarkable about the near-incomprehensibility of Einstein’s work.

At Princeton, it often seems like complete understanding is the ultimate goal, whether you’re tackling an Econ problem set or struggling through a paper on Plato — a drive towards closure and comprehension. I worry when my paper doesn’t have a clear thesis, or when I don’t fully understand the material I’m writing on. These are legitimate concerns, and ones that I should probably pay closer attention to, according to my Writing Seminar professor. Still, though, as I’ve begun to notice the reminders of Einstein and his work here that are sprinkled throughout town and campus, I take comfort in the fact that even he reached past the bounds of lucidity, unafraid to make leaps in the name of high-level theory.

To be clear, this is not to compare my muddled works to that of Einstein (I’m not certain he would be entirely thrilled with my no-problem-set approach to Princeton), but I do think there’s something to be said about embracing slightly arcane methods of thinking. May the plaques, houses, and posters that stood among wool sweaters celebrating Einstein be reminders of the importance of taking academic chances, even if it means that your R1 is missing a fully coherent thesis — who knows, maybe you’re on your way to the next theory of general relativity.

Clara McWeeny is a Staff Writer for The Prospect at the ‘Prince.’ She can be reached at claramcweeny@princeton.edu, or on social media @claramcweeny.

Self essays at The Prospect give our writers and guest contributors the opportunity to share their perspectives. This essay reflects the views and lived experiences of the author. If you would like to submit a Self essay, contact us at prospect@dailyprincetonian.com.