Princeton’s admissions system is under increasing scrutiny. As other colleges eliminate their legacy preferences, some think Princeton should do the same. The SAT, long the cornerstone of college admissions, is being abandoned to eliminate socioeconomic disparities in admissions.

Breaking down the remnants of a self-serving system for the elite is a noble goal, but nobody seems to be questioning the fundamental principle behind college admissions: meritocracy. We’re getting better and better at sorting high schoolers into colleges by merit and accepting the fact that the all-consuming nature of college admissions is inevitable. But if we created such a ridiculous system in any other context, we’d immediately recognize its absurdity.

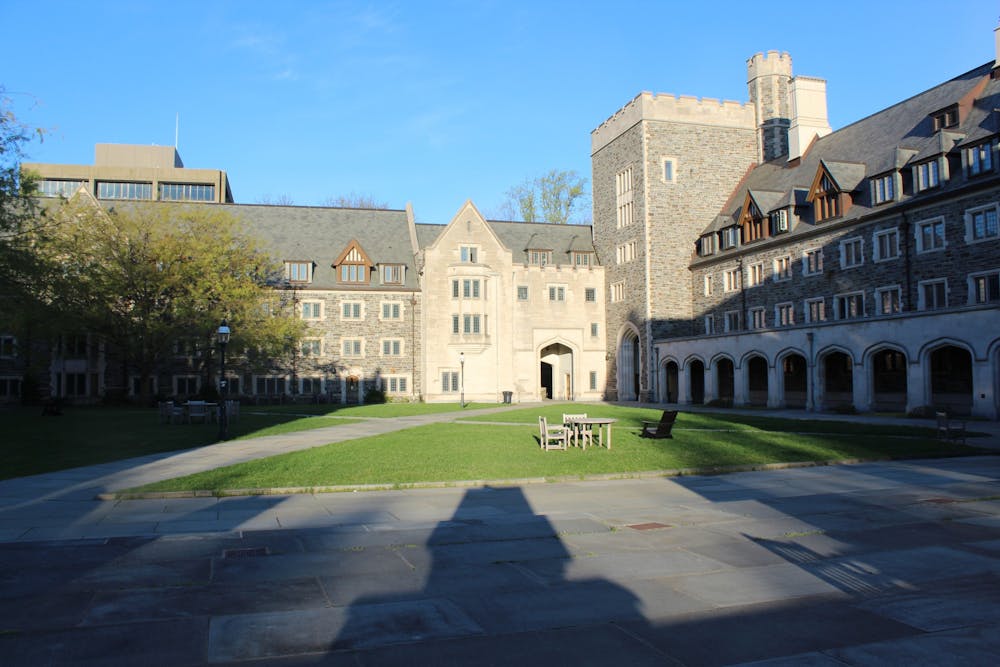

To prove it, let’s take a trip to an alternate reality. Princeton suddenly has an idea: instead of randomly assigning first-year students to one of the six (soon to be eight) residential colleges, why not let students choose which residential college they prefer? Prospective students who have a fondness for Nassau Street might choose a room in Rockefeller or Mathey Colleges. Aficionados of the Forbes dining hall might decide that living in Forbes is worth the walk. Students who like air conditioning and Soviet revival architecture might choose one of the new colleges.

But considering that the luxury of the rooms and their durability against dragon attacks are top priorities for many students, Whitman College is likely to have more applications than the others: likely more than they have room for. The Whitman College staff wonders what to do. Should they just accept students randomly? “No, no, no!” someone says, “We have to find the students who are a good fit for Whitman. Let’s have them write essays about why they want to be in Whitman.”

This idea achieves broad acclaim. So now, students coming to Princeton spend their summers refining their Whitman admission essays. And the Whitman College staff sit on the floor, sorting through hundreds of applications. “This is hopeless!” someone cries out. “Everyone has the same story about how they’ve dreamed of living in Whitman since the womb. There has to be some way to tell them apart! What we need is more data — an aptitude test and letters of recommendation. Let’s have them submit their high school transcripts. Then it’ll be clear who should be a part of Whitman College.”

So students now spend their summers balancing studying for the Whitman Aptitude Test (WAT), coaxing their friends to write letters of recommendation attesting to their natural sociability, and writing ever-more dramatic tales of how their life is really an epic quest that ends in Whitman College. And the Whitman staff once more look at the applications. “So, do you know which ones are a good fit for Whitman?” the college head asks the newly appointed admissions officer. Of course not, the admissions officer thinks, I’m an administrator, not a mystic. What on earth does a good fit for Whitman even mean? It’s a college, not an airline seat! But instead of saying any of that, the admissions officer hands over the applications with the top WAT scores, which is really the only thing he knows how to sort. “These people are a perfect fit for Whitman,” he declares, as if he could say anything else without eliminating his own position.

The Princeton School and State Report’s once-lighthearted residential college ranking is influencing more and more students’ decisions on which residential colleges to apply to, which is driving admission rates at the top residential colleges to subterranean levels. The other residential colleges feel the pressure to become more selective. “We were fourth last year! Fourth!” the Rocky College Head explodes, “We need to seem more selective. More essays! More weird requirements!”

We now move to a conference room at a top company, where the CEO chomps on a cigar and demands to hear what factors known at hiring time correlate with job performance. “Well, sir,” whimpers a data scientist vastly overqualified for her position, “among our Princeton employees, grades were a good indicator of job performance — but there also seems to be a strong correlation to what residential college they were in.” “That’s fantastic!” the CEO cries, surreptitiously firing half the recruitment staff. “Why do I need to bother identifying the most qualified applicants when Princeton already sorted them by merit their freshman year?”

Students now spend years in a furious rat race to make their Whitman application stand out and thus punch their ticket to career success. Somewhere, a student protests to their parents: “I don’t want to apply to Whitman! Everyone gets the same degree, it’s just a residential college. I have always wanted to live in the architectural manifestation of a cardboard box, which is why New College East is for me!” “Stop setting such low standards,” their parents scoff. “If you can get into Whitman, you have to go.”

A scandal erupts as it turns out Whitman has been allocating a certain number of spots to students who went to the same high school as past Whitman-ites, which of course favors the wealthy from private schools that send many students to Princeton. “It’s a tiebreaker used only in the rarest of circumstances,” the College Head lies, as if the staff could make heads or tails of the uniformly perfect applications without the use of that tie-breaker. Outside, students protest, demanding an end to the privilege. “All we want is to be judged on merit,” they chant.

But as right as they may be about the unfair tiebreaker, they’re missing the point. The whole system is a sham — a game of arbitrary sorting over a totally meaningless prize. Sorting by merit to pick a residential college has no value. If you were hiring a brain surgeon, you would sort the candidates by merit. But why do the smartest students have to live next to each other? What does that have to do with fit?

It was a great idea to have students choose between Rocky and Forbes, but are the superficial differences between the two colleges worth the years of stress the application creates? Are the differences between Princeton and Georgetown and Washington University at St. Louis important enough to justify the same system? This experiment must be judged a failure. The benefits are not worth the costs. And the same goes for college admissions.

Princeton could eliminate its admissions department and form an admissions collective with other private colleges of similar size, expense, and offerings. Students would apply once to the collective and the larger team would form multiple college classes, then randomly match each class with one of the colleges in the collective — eliminating the hierarchy between selective colleges. The collective would not include all colleges: it may not be prudent to have students randomly placed between a large state school and a small liberal arts college. But where the differences are largely superficial, a collective could better manage admissions rate deflation and dampen the absurdity of college sorting.

Princeton assigns residential colleges randomly for a reason. If only it could apply that same wisdom to the much more destructive system of college admissions that it helps perpetuate.

Rohit Narayanan is a sophomore concentrating in electrical and computer engineering from McLean, Va. He is the Community Opinion Editor at the ‘Prince.’ You can ratio him on Twitter @Rohit_Narayanan or spam his email at rohitan@princeton.edu.