Sorry, Witherspoon, you need to go

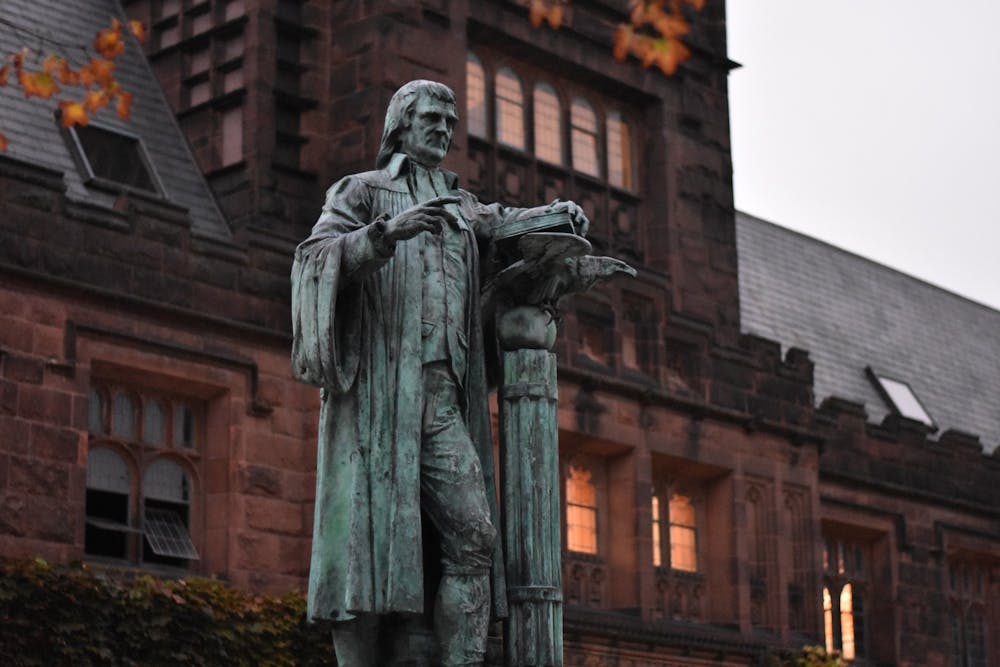

A few days ago, as I was leaving from Firestone Library, a visiting family asked me if I could take a photo of them next to the John Witherspoon statue. I obliged, but as the family posed, smiling as their hands raised peace signs, I couldn’t shake off an awful feeling washing over me.

Why hasn’t this statue been removed yet? I thought as I photographed the family and Mr. John Witherspoon — the slave owner who served as the sixth president of the University.

In response to the column by Abigail Rabieh ’25 in which she claims that “statues preserve memory,” I argue that simply conceiving of statues “in a new way,” as Rabieh suggests, would overlook a key underlying nuance of public statues — the inherent glorification they receive. To those who are unaware, such as the visiting family I photographed, it is not possible to critically reflect and observe the statue. To those who are aware, the statue manifests an uneasiness that is quite frankly a slap in the face. What we’re left with is an inappropriate statue reeking of its tainted history of oppression. We must remove the statue.

The contrarian

“Opposition and contradiction are the only means of giving it life or duration.”

John Witherspoon, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, renovator of the University, and the sixth president of the University, had a very complex relationship with slavery. He tutored African and African American students, yet publicly lectured and voted against the abolition of slavery. He characterized the slave trade as "unlawful to make inroads upon others . . . by no better right than superior power," yet maintained his slaves, whom he left behind to his estate after he passed away.

In fact, Witherspoon's descendants built their wealth on slavery, and some actively served as officers in Confederate States in their cause for secession. While it’s true that he had a large role in developing the University, his ambivalence in rejecting slavery makes the decision to immortalize him with a statue extremely problematic. We must remove the statue.

The significance of the statue

"I do not think there lies any necessity on those who found men in a state of slavery, to make them free to their own ruin."

-John Witherspoon, denying the necessity of emancipation

The usual argument made against the removal of historical statues is that we as a society need some sort of memorabilia of our past — a bookmark of our history — so as to not forgive our wrongdoings but to vow that we will not repeat our mistakes.

I find this argument to be quite absurd.

For example, statues of Adolf Hitler are seldom — if ever — seen in public. Still, most people with basic knowledge of history would know who he was and what he did. Likewise, we do not need to fervently wave around Confederate flags in order to remember and evaluate that chapter in history.

Of course, this should not be taken as a direct comparison of Witherspoon to Hitler or the Confederacy, but the point still stands: it is not necessary to remember these heinous historical figures through monuments nor monoliths, statues nor symbols. If anything, glorified statues of controversial historical figures in public spaces may even inspire the bad apples in society to follow in the wicked footsteps immortalized by the statue.

That being said, the removal of an existing statue does not necessarily insinuate that there is no reason to honor someone like Thomas Jefferson, which Rabieh implied to be necessarily true; we can continue to honor the positive things Jefferson had accomplished by keeping him alive in our history books. The same can be said about Witherspoon who developed the University into a “seedbed of revolution,” one that George Washington proclaimed to be second to none in producing estimable scholars. The problem, however, lies in our medium of acknowledgment and its resulting implications.

Troubled historical figures are sensitive, solemn subjects meant to be discovered at one’s own pace and to be internalized without the public glorification that inherently comes through devices such as statues. Thus, the idea of proudly and publicly immortalizing deeply problematic historical figures as a means to “raise awareness” of their history is a deeply flawed concept.

I reacted much in the same way that Abigail did upon learning about the dark history of those such as the Founding Fathers. I had once associated them with pure heroism and valor. However, the fact that we allowed these statues and monuments to romanticize historical figures was the cause of our initial association of them being perfect in the first place. In a way, statues contribute to this false association that Abigail mentioned in her piece.

Given the current digital revolution, accessing the history of these troubled figures has been the most convenient it has ever been in human history, completely removing the need to immortalize them in public. We must remove the statue.

The significance of the signer

"It has been objected that Negroes eat the food of freemen & therefore should be taxed. Horses also eat the food of freemen; therefore they also should be taxed."

-John Witherspoon, denying the humanity of slaves by comparing slaves to horses.

A common argument in support of Witherspoon is that he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and that his historical significance is too great for him to be fallible. Being a signer, however, was never an indication of the purity of one’s morals. Considering that Thomas Jefferson wrote the historic “all men are created equal” while there existed slaves on his own plantation, one can interpret these signers’ involvement — or lack thereof — in the fight against slavery as a sign of passive support for the institution itself, an ambivalence that helped nurture the dark beginnings of this supposedly free country. Considering further that this country was built off the backs of slaves even after statements such as “all men are created equal,” one can see that the counterargument of Witherspoon’s significance as a signer renders itself irrelevant. Besides, what to the slave is the Fourth of July?

We must remove the statue.

History repeats itself

For those still in disagreement, I offer an alternate way of looking at this topic. Suppose Witherspoon’s involvement in the founding of this country was indeed significant enough to warrant a statue in his honor. We now consider that if Princeton was able to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from the School of Public and International Affairs, completely defying the fact that Wilson was not only a president of the University but the President of the entire United States, then it would be very difficult to argue against creating change on campus in the case of Witherspoon.

This is not as radical as you may have thought it to be. In fact, the case against Witherspoon had already been gaining momentum. Princeton Middle School, formerly known as John Witherspoon Middle School, has already changed its name — and for good reason. Imagine the message it would send to impressionable youth if they had to show up each day to an institution named after a slave owner, one who never had the courage to fully stand up for what is right. Unfortunately, the message sent to them might as well be that after a while in history, famous and infamous somehow become one and the same.

If we allow it to be.

Our tolerance for the intolerable

To those on the fence regarding this issue, isn’t it strange how we find ourselves in the very same ambivalent position that Witherspoon once held? Witherspoon rejected the idea of slavery yet continued to maintain slaves. Princeton rejects the idea of oppression yet continues to venerate the accomplices to that very oppression on campus. Although statues preserve memory, they inherently glorify it as well. Memories can be preserved in so many ways; if shady statues of historical figures must exist for the sake of reflection, then they should be in museums rather than on an open campus.

As for the University as a whole, I am proud that we have established clear acknowledgments but do understand that this is the bare minimum. We must take a firmer stance and address our past no matter how troubling it may be. We’ve already demonstrated that we’re capable of doing so in the case of Wilson and the School of Public and International Affairs. If we remove the Witherspoon statue, and perhaps even his namesake from places like Witherspoon Hall, we can rectify our history’s shortcomings.

Windsor Nguyễn is a first-year student from Appleton, Wis. He can be reached at mn4560@princeton.edu.