All around us, there is catastrophe: We are living in the second, almost third year of a global pandemic, and the death count continues to tick up every day. We see the consequences of the continued climate disaster: Fires engulf more land than we can remember, while natural disasters lead to death and panic even here in Princeton. Racism continues to claim the lives of countless people of color across the country. Every day seems to bring more bad news; every day feels one step closer to the apocalypse.

But the worst problem facing us at Princeton? According to Dean of the College Jill Dolan, too many students are getting As, and for some reason, that’s a bad thing. I might argue otherwise: Students shouldn’t be getting grades at all.

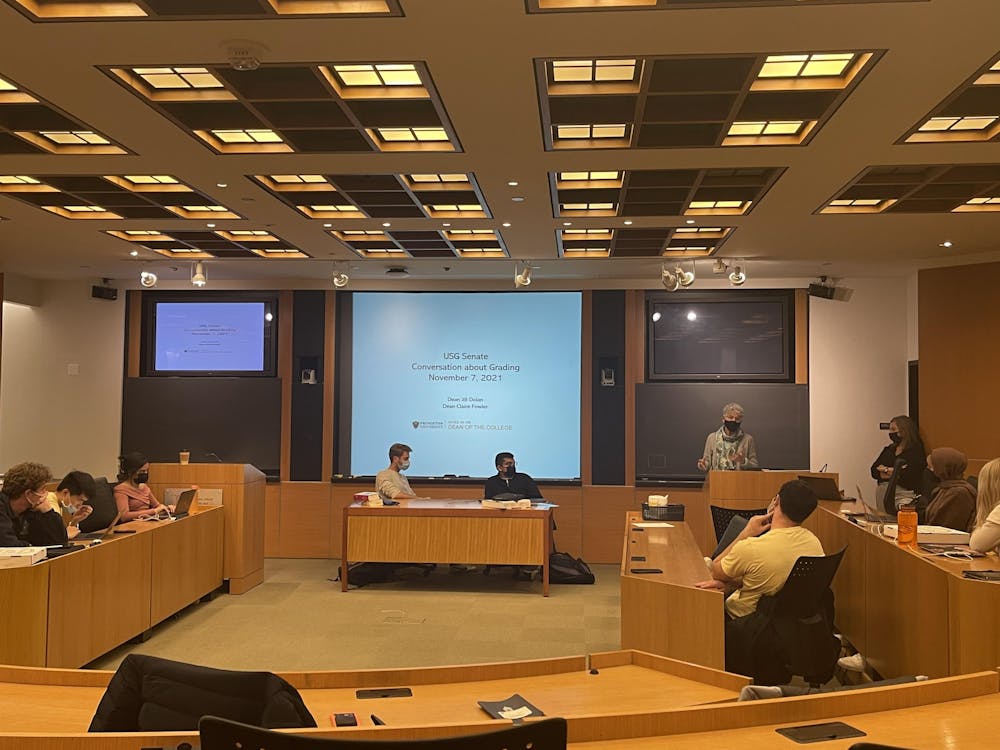

Here at the “best damn place of all,” administrators recently voiced concern over the number of high grades that students are receiving in their courses. Deans Dolan and Fowler began a presentation to the USG Senate on grading policy by citing a “steep increase in the [number of] ‘A’ grades.” In a world that praises student success, should we not be celebrating this achievement by Princeton students? Apparently not. Following the Deans’ reasoning, students must not be given a false sense of success — the hierarchy of grades must be preserved.

Even after students were sent home due to the pandemic back in the spring term of 2020, Princeton’s academic administrators continued to convey the message that the rigor of Princeton coursework must be maintained.

“I can’t stress enough how important it is for you to continue your coursework this semester,” Dean Dolan sent in a March 19 email, just days after students were sent scrambling to pack, store, move, and otherwise upend their lives as they knew them.

The stress on “rigorous” work has persisted throughout the pandemic — a professor told me that they have been reminded as recently as this semester to ensure that the rigor of their courses is maintained. While this suggestion might not be a direct response to the increase in As, this coincidence seems to suggest that academic administrators would prefer that we make classes even more difficult than they already are.

But the academic environment at Princeton already challenges students to their limits. We saw the consequences of that rigor in the concerning number of CPS appointments made last semester. In other instances, we witness these difficulties on the faces or in the words and actions of our fellow students. It already proves difficult to establish genuine connections with other people because of the pressures of extracurriculars and academics.

Upon examining this continued maintenance of rigor, it is worrisome to think about what administrative solutions might be implemented in the future to stymie this proliferation of good grades. Might we usher in another era of de jure grade deflation? This all seems to lead to a troubling conclusion — that the reason for grades is not to measure student success, but rather to ascertain the degree of a student’s failure. And some students have to fail in order to keep this game going.

The fear of failure already motivates so much of Princeton students’ lives: We stay up late in fear of a bad exam grade, sacrificing precious sleep that our body needs to try and eke out a few more points. Our interactions with friends must exist out of convenience, because we cannot dedicate enough time to cultivating our relationships without sacrificing time that could be spent studying or looking for jobs, and our leisure time is constrained only to whenever we feel we can sacrifice minutes that we could be spending doing work to instead do something that makes us happy or, better, healthy.

Some might argue that an increase in Princeton students’ GPAs will make it more difficult for students from other universities to get jobs. This is a problem worthy of consideration. But the solution is not to make Princeton even more competitive. Princeton is plenty competitive, with students often shouldering the responsibility for their own self-care and rest, ignoring the institutional pressures that make this care necessary in the first place. An alternative, then, might be to simply eliminate grades.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it many challenges, but it also presents an upheaval that Princeton might be able to exploit (in ways aside from increasing the endowment). As one of the most prestigious universities in the country, we have an opportunity to revolutionize the way we assess learning, and demonstrate that Princeton students are highly capable simply by virtue of attending this school because they are, regardless of anything that grades could say about them.

This remedy might even prove to be a cure-all: professors will have more latitude in ensuring students are truly learning — not destroying themselves over a grade — and, students will have more opportunity to structure their lives at Princeton around the things they value, prioritizing connecting with people and taking care of their bodies, rather than shunting away friendships, relationships, and self-care to cater to their exorbitant workloads. Students shouldn’t have to suffer over such arbitrary things. We need to get rid of the grades.

Josiah Gouker is a senior in the Department of African American Studies from Yucca Valley, California. He can be reached at josiahg@princeton.edu.