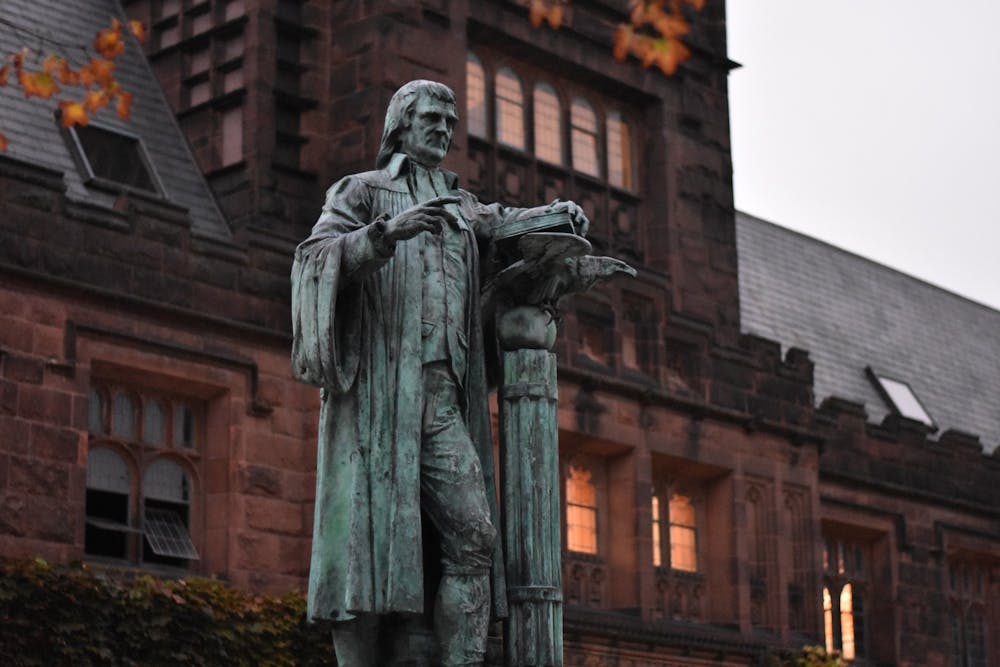

On a windy Thursday in late October, I stood outside East Pyne Hall with the rest of my Humanities Sequence precept, gazing up at four statues built into the west side tower. The statues honor four important members of the Princeton community: two former University presidents, John Witherspoon and James McCosh, and two alumni, James Madison Class of 1771 and Oliver Ellsworth Class of 1766. We were discussing the particular function of art in the context of a building and a campus, and all I could think about was what we did not discuss but was central to the readings we did to prepare for the precept: the relationship between the men and slavery.

In my readings, I learned that McCosh was a vocal opponent of slavery, but the other men all had more complicated views. Madison thought slavery was a blight on America, but owned over 100 slaves. Ellsworth was in favor of the three-fifths compromise. And though Witherspoon thought religious education was important for all men regardless of race and he tutored several freed slaves, he owned two slaves. I didn’t know what to make of this discovery — is it okay to have these statues on a campus building? How do we remember historical figures who did both good and bad things? Can we honor them for the good and not the bad?

Last month, these questions were up for contention when the Public Design Council in New York City agreed to remove a statue of Thomas Jefferson from the New York City Council Chamber.

Thomas Jefferson played many key roles in the creation of the United States: he was the leading author of the Declaration of Independence, he advocated for religious freedom in America, and he was the third President. He also owned over 600 slaves.

As a lover of American history, I was initially indignant when I heard about this removal. I associate Jefferson with the very ideals on which our nation is founded — that all men are endowed “with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” I think of his work in Virginia to establish protections for free practice of religion. I think of the Louisiana Purchase. These acts are how we celebrate and remember Jefferson. It is telling — and deeply problematic — that I do not immediately think of the fact that he owned other people.

My instinct is to say that we should be able to compartmentalize Jefferson’s actions. This country would not exist without him, and as American citizens or residents, we should honor him for making all of the freedoms we find in this country possible. But when I try and put myself in the shoes of other Americans, who have a much more personal connection to slavery, I find this difficult. As a Jewish person, I don’t think I would feel comfortable if I often saw statues in honor of Henry Ford or Charles Lindbergh. Even if those statues were meant to commemorate their great achievements as American citizens, I would not be able to ignore the fact that both were raging antisemites.

I understand why Jefferson’s statue was removed. I am horrified that he owned slaves and find him to be a walking contradiction. How could he write that “all men are created equal” and return to a plantation where he treated people as sub-human? However, I also don’t think that removing it was the right call. Inez Barron, one of the members of the council that removed the statue said that “we're not waging a war on history … we want to make sure that the total story is told, that there are no half-truths and that we are not perpetrating lies.” But removing the statue is a lie. It signifies that there is no reason to honor Jefferson; this is not true. He was a remarkable man, and we owe the basic tenets of our country to him.

Perhaps instead of tearing down statues of complicated historical figures (and it’s hard to find an uncomplicated one), we should conceive of statues in a new way. Instead of viewing statues of Jefferson as monuments to his greatness, we should view them as a testament to his life, in which he was not simply a heroic patriot and not simply an evil racist. Statues preserve memory. We should remember Jefferson for the great work he did and for the terrible things he did.

If we continue to educate ourselves on the complicated histories of the people we admire, then statues will serve a new purpose. Now that I understand whom the statues on the East Pyne Hall tower represent and know more about their lives, I will think about the full range of impact those men had on the University and the country as I walk through the archway. I will think about their role in shaping this university, and I will think about the appalling ways in which they treated other people.

I hope that every student will eventually have the same context when reflecting on these and other statues on campus. We cannot ignore the difficult history of Princeton when we are benefiting so much from it. Both around our campus and the nation, we must stop selectively honoring people for certain goods and ignoring the bad and instead remember them for everything they did — who they helped and who they hurt. That way, we can all understand the wonderful and terrible context in which we live.

Abigail Rabieh is a first-year columnist from Cambridge, Mass. She can be reached at ar5732@princeton.edu.