The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone.

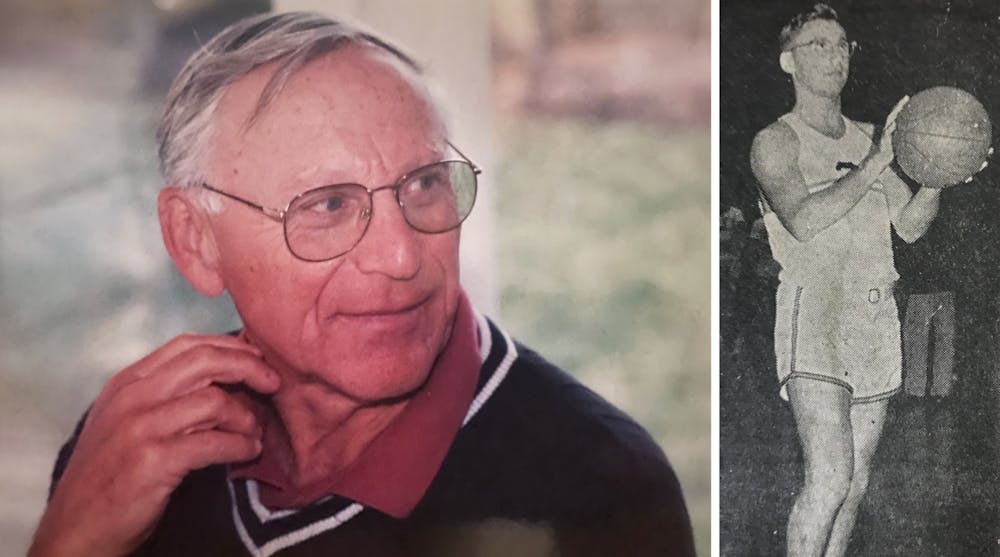

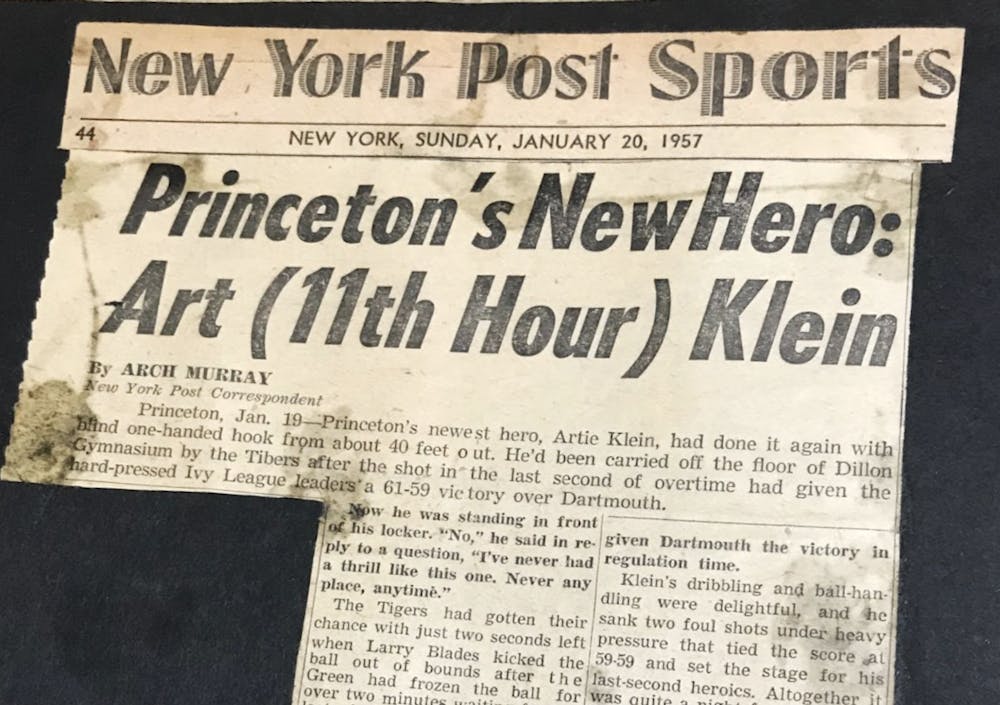

To me, he was Grandpa. But to the 3,000 fans in Dillon Gymnasium on Jan. 18, 1957, he was a miracle. Or as The New York Post called him, “Princeton’s New Hero.”

Why? Little Artie Klein threw a 42-foot, over-the-shoulder blind hook shot to defeat Dartmouth with one second left in overtime, placing Princeton first in the Ivy League.

The announcer said:

“Klein over the ... SHOULDER. IT GOES IN! THAT WAS THE MOST FANTASTIC SHOT I HAVE EVER SEEN IN MY LIFE!”

After my grandpa passed away in 2008 from pancreatic cancer, my dad gave my sister and I CDs of the commentary from the game, which is still ingrained in my memory. I can hear it when I close my eyes, followed by the static muffling of the entire gym erupting in cheers.

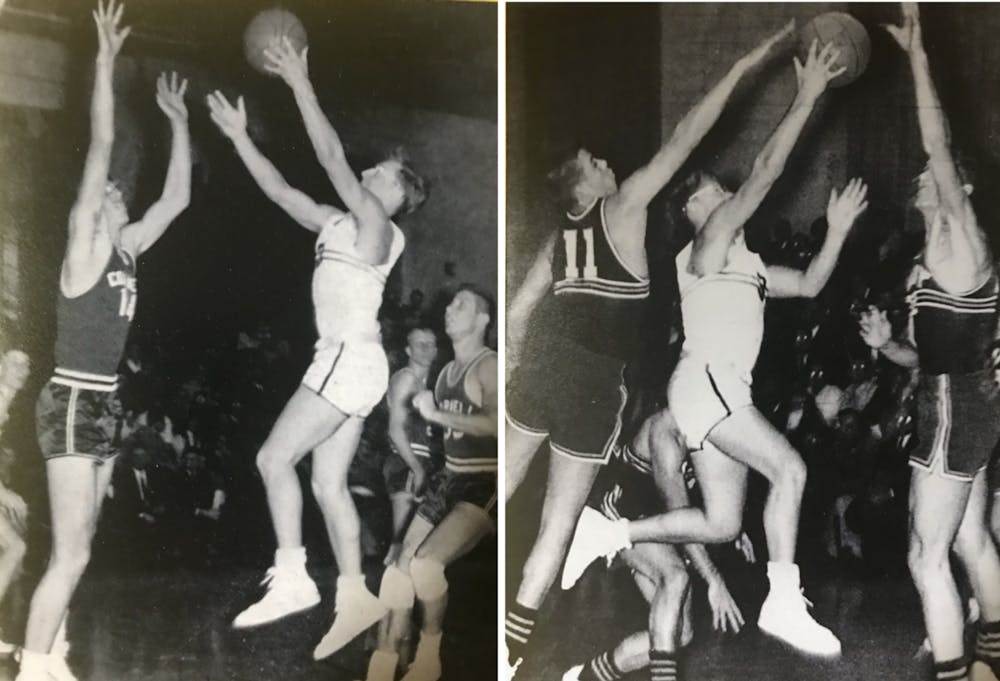

(Left) Little Artie Klein going up for a shot against Cornell Big Red. (Right) Little Artie Klein airborne and in action.

Courtesy of Megan Klein

Growing up, Artie was the new fifth grader on the block after moving to Malverne, N.Y., but it didn’t take long for him to settle in.

When he wasn’t at school or at home, he could be found down School Street at the corner court, practicing his game. He always said foul shots were never to be wasted, something he would prove true a few years later.

In high school, he was “Malverne High’s ace play-maker” and made the local paper’s All-Star high school basketball team more than once. When it was time for college, he applied to every Ivy League school and got into all of them.

“I received numerous basketball scholarships, but someone from Princeton recruited me, and, as soon as I saw the school, I knew that was where I wanted to go,” my grandpa wrote in his eulogy before he passed. “Princeton didn’t give athletic scholarships, but my parents, who had modest income, supported my decision, and off I went.”

On May 10, 1955, he received a letter from Princeton’s Head Coach, F.C. Cappon, who wrote, “I assure you that you will never regret deciding to further your education at Princeton.”

Fast forward to that January night in 1957, when a Tiger win would place them first in the Ivy League Conference, pushing the defending champion, Dartmouth, aside. With five minutes left in regulation and down by nine, Artie stepped onto the court, and Princeton came back.

Three minutes into overtime, he was given the chance to tie the game with two foul shots. It was like he was back at home in Malverne, shooting free throws at the corner court. He tied the game 59–59.

With about a second left on the clock, Princeton called a timeout to decide how to secure the win. The play didn’t involve Artie, but when the player who was supposed to get the ball was blocked, he was wide open and ready.

After being passed the ball, Artie whirled it over his shoulder without even looking. The miracle shot swished right through the basket, nothing but net. The buzzer sounded, and the game ended at 61–59. The last four points were Artie’s, and he was the hero of the night.

A newspaper article from The New York Post.

Photo courtesy of Megan Klein

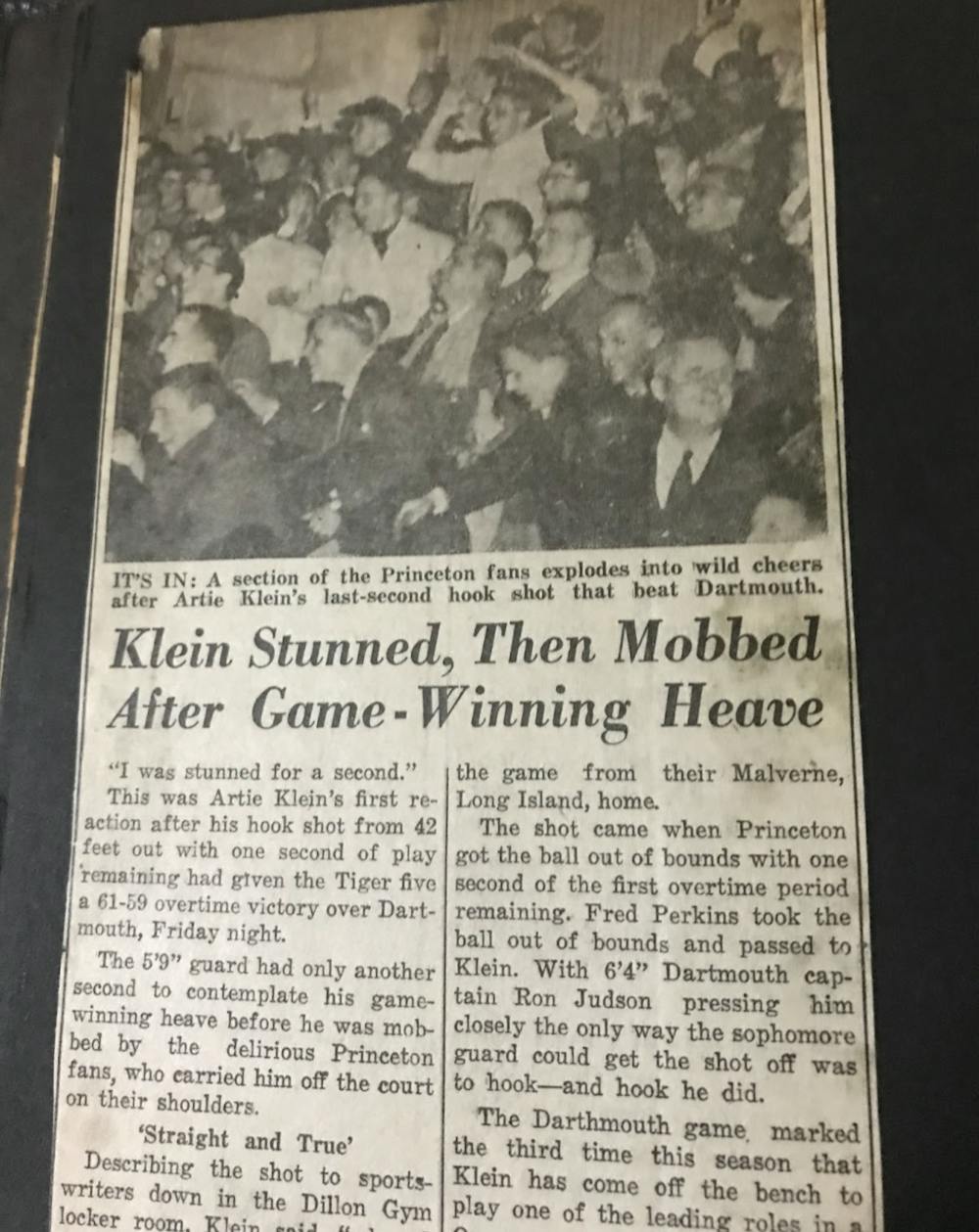

The crowd and his teammates immediately mobbed him, and he was lifted onto their shoulders and carried off the court. The screaming in the gym went on for five minutes.

I can still hear his voice from the CD, Long Island accent and all,

“When the ball first went in, I just couldn’t believe my eyes. But of course, it’s my greatest thrill, and I’ll probably never have anything like it again either.”

Newspaper article from the game, showing the crowd going wild after Artie's shot.

Photo courtesy of Megan Klein

The Real Post Game

Once he graduated, Artie went into the Army Reserves and got an MBA from Columbia before finding his place at Young & Rubicam, a global advertising agency. This is where he met Sandi, in his words a “young, cute girl with long brown hair.” They were married within seven months.

He wasn’t known to flaunt his Tiger stripes after college. He kept in touch with his teammates and would occasionally go to a football game, but the tales of his legendary accomplishments stayed in New Jersey.

“He didn’t live in the past, he lived in the present, mostly because that was his family,” his wife Sandi Klein said. “But he did love Princeton and was very proud that he went there, that was an important part of his life.”

He was just innately humble. Whether it was his athletic and academic achievements or business successes, he always left those at work, at school or on the court.

“[Our] father used to say about him, ‘I’d love to be a fly on the wall to listen to him when he’s either talking or lecturing or doing business,’” Artie’s sister Roz recalled. “He never talked about that stuff. He was unassuming. He never bragged. He never boasted. He was just Arthur.”

Artie Klein (far left) and his teammates sporting their uniforms and Converse Chuck Taylors.

Courtesy of Megan Klein

One of my earliest memories of him was in the driveway of my dad’s childhood home. He taught my twin sister Alexis and me how to properly shoot a basketball with his “BEEF” technique: bend the knees, elbow in, eyes on the basket, follow through. He never got to see Alexis, who captained our high school basketball team, put BEEF to use in her nonchalant three pointers.

We were eight years old when our parents sat us down in the basement one August day to tell us Grandpa was sick. He went to the doctor with horrible back pain and left with a diagnosis of Stage Four Pancreatic Cancer.

It took time for me to understand what it meant to lose someone, especially to lose a grandfather. I don’t remember much from the funeral, but I do remember a group of men speaking. His former Tiger classmates were now there for his other team, his family.

When Grandpa got sick, one of the Dartmouth players from that historic game decades before gave him a call when he heard of the news. He wanted Artie to know that after all these years, he still remembered his amazing buzzer beater shot.

Just how he never boasted of his accomplishments, Grandpa never complained much either. I remember him sitting on the edge of the pool the month of his diagnosis, wearing an orange polo (a switch-up from his usual muted yellow) and khaki shorts, legs dangling in the deep end while I swam around. I didn’t know the excruciating pain he was in. All he did was hunch over a bit and smile.

Five months later, he was gone.

The last time I saw my grandpa, I leaned over the couch he hadn’t left in weeks and whispered in his ear that I loved him.

Ever since then, I’ve done my best to make him proud.

Grandpa, you were once Princeton’s hero. But you’ll forever be mine.

Megan Klein is a senior at Boston University majoring in Journalism and minoring in Holocaust, Genocide and Human Rights Studies. She hopes to combine her love of sports and communications after graduation.