Among the many losses of the past 18 months, the loss of international travel opportunities through the University is often forgotten. Many students traveled independently this summer or during gap years, and Princeton students were more than happy to take internships domestically in the absence of viable programs abroad. As ever, Princeton students adapted creatively and constructively to the loss of typical study-abroad activities, but this does not mean we should not reflect on this loss.

Travel is a privilege, and part of the typical privilege that accompanies attending Princeton is the ability to explore a foreign country, language, or culture, often on the University’s dime. But travel is not mere self-indulgence either — it allows us to enact what we have learned in the classroom. Whether by improving language skills, reading great works of the humanities, or mastering principles of engineering or international relations, every Princeton student has learned something which can contribute to people and places outside of the U.S., and every Princeton student has much to learn from their time abroad.

Travel, certainly, played an essential role in the development of our own national self-identity. On the one hand, founding fathers like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson learned to think deeply about representative government, Enlightenment ideals, and international politics during their time in France. On the other hand, the acknowledged contemporary masterwork on early American institutions and manners — “Democracy in America” (1835–1840) — was written by a Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, after a trip abroad in America. American narratives of travel have rightly often focused on immigrants seeking a better life on our shores, but our country has also benefited greatly from the fresh eyes of foreign travelers, seeing what we have grown too used to, while teaching us to see more deeply who, as a people, we are.

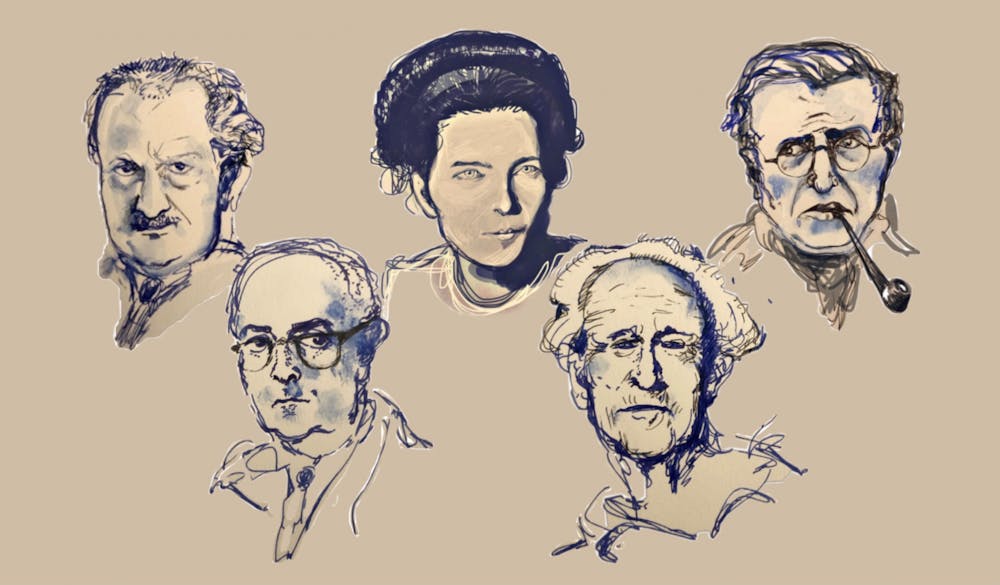

Recently, I’ve been thinking about these questions of travel and education, and how they relate to American history, while reading Sarah Bakewell’s “At the Existentialist Café” — a 2016 book on the lives of existentialist philosophers, including Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Edmund Husserl. Many of the philosophers Bakewell writes about were interested in these encounters with other peoples and customs, of seeing and being seen, and the thrills and perils of a new way of living abroad.

The German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) was captivated by those moments in history when, as Bakewell puts it, “cultures were encountering each other through travel, migration, exploration, or trade.” These kinds of meetings led to the awareness, among all parties, of a “home-world” and an “alien-world,” the realization that one’s ways of doing things are not given but rather merely one option among many. The work of philosophy, in Husserl’s view, was to pursue the self-questioning that was ignited by meetings with “alien-worlds”: why do we do things this way? What can we, as human beings, have in common with those other “strange” people? Should we change our way of living or running a society after seeing how they do it over there? The germ of all these questions lies in those periods of history where people encountered each other in new ways, leading to questions about themselves and the way they lived, and new developments in philosophy and other fields of human knowledge.

Husserl died in 1938, just before his country and Europe as a whole plunged into the darkness of World War II. He couldn’t have known that the calamity of World War II would lead to one of these most interesting periods of cultural encounter and exchange, as French and German thinkers — among the greatest philosophical minds of the age — came to America as refugees and tourists, and turned their powers of perception and judgment onto our country in the late 1940s. Just as de Tocqueville’s observations are a gift to any American seeking to understand his or her country through the eyes of another time and culture, the stories of the continental philosophers’ travels and sojourns in America show us much about a forgotten moment in our national past, about who we are and always have been as a nation, and about what impact this country and its culture had on intellectual history in Europe.

The visits of Camus, Sartre, and de Beauvoir to the United States in the late 1940s took place in a time of great cultural infatuation between the United States and France. The Americans had just freed France from Nazi occupation, and the Paris of the existentialists was eager to learn from the Americans flooding into the city from abroad, visiting the city for the first time since before the war. Sartre, Camus, and de Beauvoir would return the favor in the years to come, travelling to America on lecture tours and leaving written records of their impressions. The existentialists threw themselves into the bright array of high and low American culture, delighting in dime store novels on gangsters and hitmen together with the works of Faulkner and Hemingway, jazz clubs and comedy movies, revelling in these uniquely American contributions to culture. De Beavoir was dazzled, if a little unsettled: America was “abundance,” in her words, a “crazy magic lantern of legendary image.”

My favorite of the reports on America from this period that Bakewell discusses, though, has to belong to Camus, who wrote of New York and “the morning fruit juices ... the anti-Semitism and the love of animals — extending from the gorillas in the Bronx Zoo to the protozoa of the Museum of Natural History ... the barber shops where you can get a shave at three in the morning.”

Camus points out the striking and the mundane, the great shames of our history (Camus and the other existentialists despised American racism and antisemitism), and the things we hardly even think of as our own. I would never have thought of a love of animals and fruit-juices as distinctly American traits, but through the eyes of a traveler, from a different time and place, it emerges that they are. The existentialists gave us their impressions of our culture and our national life, reflecting on our character through their experience and writing.

In turn, they took elements of our culture back with them, as Camus incorporated noir and detective-novel themes into his later work, and Sartre and de Beauvoir maintained a life-long love of jazz. They were, in short, model travelers, bringing their critical faculties to a society foreign from anything they had encountered before, yet open to being changed by what they found.

The delight that the existentialists took in their trips to America was enhanced by a long period where, because of the Nazi occupation, they themselves could not go abroad. COVID-19 has made the last 18 months not a renaissance of interchange and travel, of shared ideas and culture, but a slog of getting by and getting through, if we are lucky. Travel abroad, for many of us, has been sorely lacking thus far in our Princeton education. But the times of learning from the outside world always return, and when they do we would be wise to seize the opportunities we are given. The philosophers of the 20th century learned much and were changed much by their travels and stays in America; what might we learn when we can travel ourselves?

Tommy Goulding is a Contributing Writer for The Prospect at the ‘Prince.’ He can be reached at thomaswg@princeton.edu.