The day I went to see “The French Dispatch,” it was raining hard in Portland — more than the usual misty drizzle — but a long queue had already formed outside the theater more than 30 minutes before showtime. The date was Thursday, Oct. 21; the time — 7 p.m. PST, marking the first showing of the night at The Hollywood Theatre and one of the first public screenings of “The French Dispatch” anywhere. After several COVID-related delays, the film’s release was much anticipated by critics and cinephiles alike. Originally meant to hit theaters July 24, 2020, the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on July 12, 2021, and was officially released in the United States and the United Kingdom on Oct. 22, 2021.

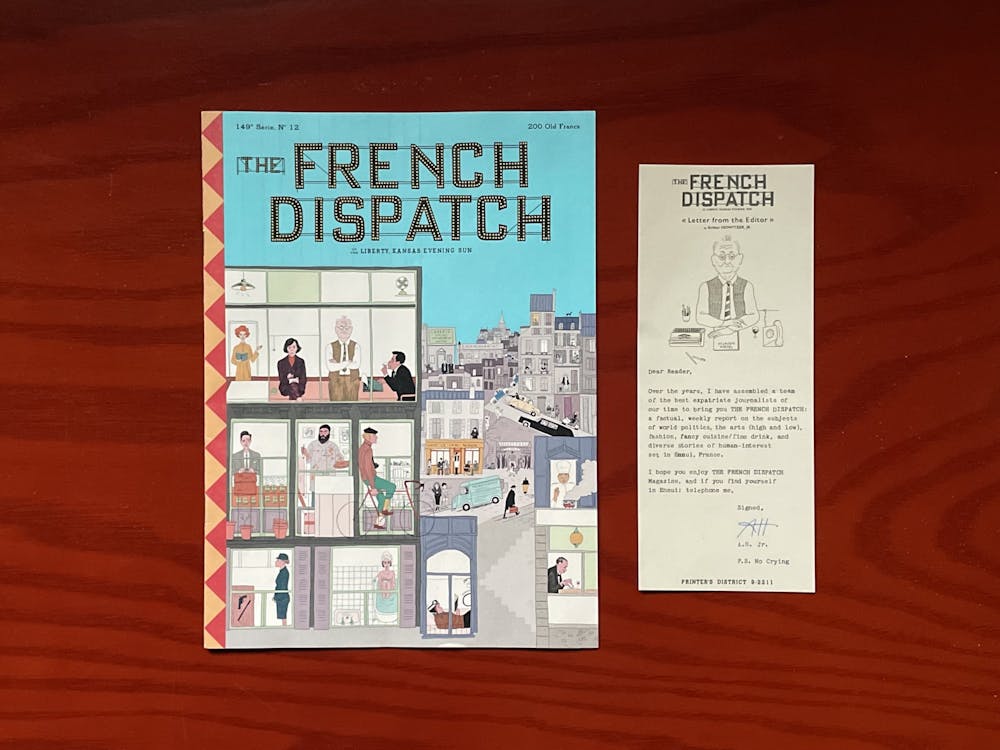

Heralded as Wes Anderson’s “love letter to journalism,” the film follows the ins and outs of a fictional American newspaper called “The French Dispatch of the Liberty Kansas Evening Sun,” based out of the also fictional French city of Ennui-sur-Blasé. The entire paper — from its reporters and its founder, to its typography and layout design — draws inspiration from The New Yorker, particularly during the magazine’s mid-20th century heyday when it patronized the likes of A.J. Liebling and James Baldwin. Facsimiles of The French Dispatch newspaper distributed at The Hollywood Theatre as “film programs” were printed to the exact dimensions of The New Yorker, with a stylized layout that mimicked the original.

Anderson first discovered The New Yorker as an 11th grader in his high school library and, as an aspiring fiction writer, was especially drawn to the magazine’s short stories. Echoes of his past literary aspirations reverberate all throughout his latest film. My experience of “The French Dispatch” felt more like reading rather than watching a movie, punctuated with wonderfully literary descriptions of Ennui that are reminiscent of Charles Baudelaire or Rainer Maria Rilke.

The form of the film itself takes after a periodical: three “short stories” serve as the primary content, with brief bookends and other (sometimes literal) paratexts to help orient the viewer. Each story, told from the perspective of the fictional reporters, oscillates between narration and live action. With a stunning array of shifting tableaux, we get the sense that we’re paging through full bleed magazine spreads.

It’s Anderson’s ability to maintain this tension between authenticity and artifice that makes his Impressionistic style absolutely perfect for a film about The New Yorker. Much like Anderson, The New Yorker has cultivated a very particular aesthetic, perhaps best characterized by the magazine’s mascot — a dandy-like figure named “Eustace Tilley.” The modern art critic Clement Greenberg once called the publication “high-class kitsch for the luxury trade,” denouncing it as a middlebrow periodical which masquerades around with highbrow (avant-garde) material. If anything, the near ubiquity of New Yorker tote bags validates his claim, suggesting that the publication is more about style than content.

The same is often said about Anderson, too. Many criticize the auteur for being too self-indulgent with his extravagant cinematic landscapes, at the expense of well-rounded, empathetic characters and culturally-sensitive plots. Some argue that the romanticized portrayal of journalism in “The French Dispatch” points straight towards Anderson’s privilege undercutting all his films.

To an extent, they’re right: Anderson’s films are first and foremost a feast for the eyes, perpetuating a tradition of ocularcentrism in Western art established by white male artists — a lineage Anderson fits right into. A part of this sharp visual aesthetic is the blunt, quick-fire delivery of lines, which can make his characters seem as though they are lacking in depth and emotion. Everything in the world of Wes is precise, calculated, and expertly staged — performative artifice at its very best. If The New Yorker is kitsch, we might say that Wes Anderson is camp.

The cast of “The French Dispatch.”

Cammie Lee / The Daily Princetonian

In her 1964 essay, Susan Sontag described camp as “a vision of the world in terms of style — but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not … And the relation of Camp taste to the past is extremely sentimental … The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance.” This certainly sounds like Anderson, whose films constantly remind us that they are highly crafted, often drawing aesthetic inspiration from a bygone era.

Anderson is known for using highly saturated cotton-candy colors evocative of Impressionism (this frame at 0:24 from “The French Dispatch” reminds me of Monet’s “Impression, Sun”), as well as straight-on extreme long shots, which create his signature “dollhouse effect.” These stylistic choices — among others — not only generate the beautiful, dreamy aesthetic that so many strive for, but much like the Impressionist paintings Anderson is so enthralled by, also reveal the artifice of the medium and prevent us from accepting film as a realistic depiction of life.

Anderson hikes up this artificial stylization in “The French Dispatch” with additional post-production flourishes — superimposing headlines onto select frames, playing with the placement and appearance of captions, fading in and out of monochrome and color, and towards the end, even abandoning film altogether for animation instead. While we might view this as Anderson’s attempt to assert the autonomy of film — as well as his expertise as a filmmaker — I want to suggest that this overload of film techniques actually has the effect of making the movie seem even more bookish. The animation during the third story, for instance, is awfully similar to The New Yorker’s cartoons and illustrations.

In many ways, “The French Dispatch” is the campiest of Anderson’s films — not only in its conceptual imitation of The New Yorker via its plot, but also formally, in how the movie presents itself as more “book” (or magazine) than “film.” Does this do a disservice to journalism? On the contrary, I think it’s what makes the movie so charming. (We also have to remind ourselves that this is a film inspired by The New Yorker, not The New York Times — we’re talking about different personas here.) Through all the gloss, it’s not The New Yorker that gets caricatured by “The French Dispatch,” but rather, the seriousness of the events and personalities the magazine documents — even the blasé city itself.

“Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature … Camp is a tender feeling,” Sontag wrote. There is no doubt that Anderson takes his art very seriously — the visual symmetry and harmony of his films indicate that extraordinary care went into the production of each frame. To dedicate an entire film to The New Yorker, then, is a declaration of love which suggests an implicit understanding of the sacrifices one must make in service of their craft.

Taken as an ode to journalism, “The French Dispatch” is suffused with emotion, purposely forgoing all seriousness so that we, the audience, have permission to view the life of a journalist through rose-colored glasses. “The French Dispatch” camps so we can enjoy ourselves and, more importantly, so we can experience the joys of modern life.

Cameron (Cammie) Lee is a Head Editor of The Prospect. She also writes about contemporary art, pop culture, film, and Asian (American) identity, and can be reached at cameronl@princeton.edu, or on Instagram at @camelizabethlee.