Princeton is an incredibly competitive institution. During its most recent application cycle, the University accepted only 3.98 percent of applicants. But, as most undergraduates come to realize during their time at Princeton, competition does not end with admission.

Princeton’s extracurricular clubs are notoriously competitive as well. Everything from dance teams and a capella groups to entrepreneurship organizations and consulting clubs require applications or auditions. Given that Princeton’s clubs are drawing from an applicant pool made up of some of the most motivated young adults in the country, getting into one of these exclusive groups can be quite a feat.

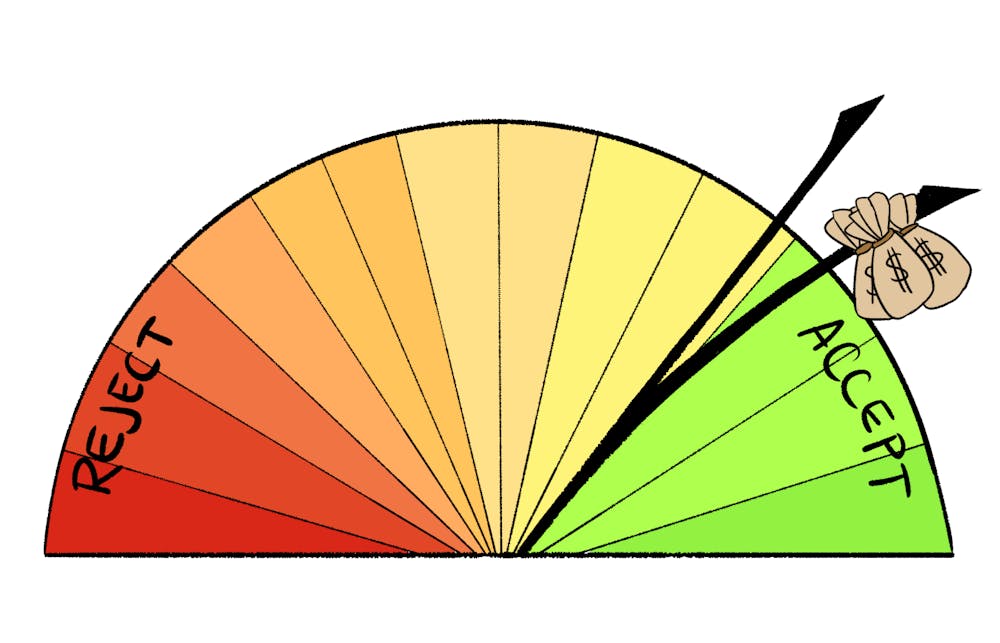

In an ideal world, clubs would not require applications. The unfortunate reality is, however, that the number of applicants often exceeds the quantity of available spots in a student group. Little can be done to change that. But there is an element of the club application process that requires our attention: much like the college admissions process itself, the club application process at Princeton favors high-income individuals.

There is no denying that the college application process favors the wealthy. More disposable income means greater access to expensive extracurriculars, private schools, and well-funded public schools. The same factors that make high-income students more likely to be admitted to competitive colleges also increase their chances of being welcomed into highly selective extracurricular groups.

Low-income students are less likely to participate in costly after school activities, resulting in what “The Atlantic” refers to as “the activity gap.” The schools low-income students attend are less likely to offer niche extracurriculars, such as active school papers and programming clubs. In short, low-income students have, on average, less exposure to the kinds of activities offered at Princeton than their higher-income peers. But does prior experience in the extracurricular in question benefit club applicants?

In their advertising, many of Princeton’s clubs claim that no experience is necessary to join. Students habitually complain that such statements are false and only make stomaching club rejections more difficult. I am not here to evaluate whether such claims are true or false. What I will argue, however, is that even when clubs genuinely are not concerned with applicants’ prior experience, the club application process nonetheless favors applicants with certain skill sets — skill sets that well-funded public schools and private schools tend to emphasize.

Take for example Model United Nations. I spoke with Sophia Richter ’23, captain of the Princeton Model United Nations Team (PMUNT), to gain insight into PMUNT’s application process. When asked what makes for a successful PMUNT applicant, Richter answered: “We are definitely not looking for experience. We take people every single year who don’t have any Model UN experience and sometimes don’t even really know what Model UN is. We are much more looking for people who are good speakers, who understand policy well … We also look for people who seem like they are leaders.”

The skill set expected of PMUNT applicants — public speaking and leadership ability — is significantly easier to develop at the type of schools high-income students tend to attend. Such schools tend to have smaller class sizes, which increases students’ chances to speak up in class. Such schools also foster leadership skills via their broad club offerings. This is not to say that low-income students cannot be effective public speakers or leaders regardless of past experience. I am simply pointing out the unfortunate reality that high-income students are more likely to attend high schools that encourage the development of certain skill sets, public speaking and leadership among others.

Thus, academic clubs’ application process often favors high-income students. But what about competitive creative clubs, such as a capella and dance groups? Simply put, the skills artistic groups seek in their applicants are expensive to develop. For example, an hour-long music lesson in the US costs above $60 on average. It is precisely these costly lessons that help applicants get into groups such as the Princeton University Orchestra. On the same note, a naturally talented singer who has taken years of expensive singing lessons likely has an advantage over an equally talented singer with no formal training during an a capella audition. The same principle can be applied to dance lessons and athletic coaching.

So what can we do to make access to extracurriculars more equitable at Princeton? The answer is different for every club; dance teams will obviously have different considerations than consulting clubs. But PMUNT offers a good example.

According to Richter, “in the first round [of PMUNT tryouts], the first portion is country speeches, but the second portion is actually a game that tests critical thinking. It has absolutely nothing to do with policy or really Model UN. That gives a real advantage to people who don’t have experience to show their ability to come up with creative solutions.” Including a non-traditional element, such as a game, in the application process can alleviate the stress of applications and allow students of all backgrounds a more equal chance to shine.

As for artistic clubs, making the audition process more equitable provides more of a challenge. But groups that do not do so already could offer a handful of training sessions before formal auditions, during which applicants would be taught the fundamentals of the artistic form they are interested in.

The majority of clubs’ application cycles have come to a close this semester, but another application cycle looms around the corner. For those readers who have the power to make the club application process more equitable, I urge you to take the time and effort to do so.

Genrietta Churbanova is a sophomore from Little Rock, Ark. She can be reached at geaac@princeton.edu.