In Part 1 of the Princeton Listserv Team (PLT) series, I determined that we ought to have a central advertising listserv, instead of six nearly identical res college listservs. To put my theory to the test, I launched a pilot: the Princeton Listserv Team. Ultimately, I found that even a single advertising listserv might be too much to handle, but a solution could be multiple subject-based listservs to cater to varying interests. These ideas are left to the next generation of Princeton students to implement, with my hope that we will eventually achieve systemic change.

The idea behind the PLT was that it would be a central email account to which one would send an email, and that email would be forwarded to all six residential college listservs. I did this by creating a custom Gmail account, which would then automatically forward emails to my friend, Andrew Wu ’21, to send out.

Figure 1. Andrew Wu sending many emails to the res college listservs in mid-April.

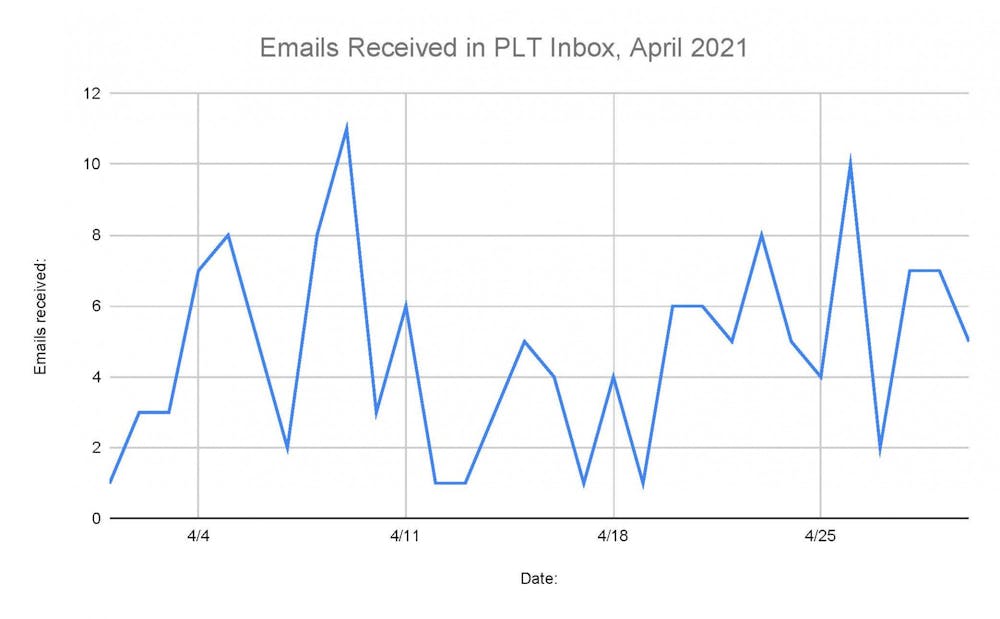

The PLT was almost instantaneously adopted by students and groups. To put it in perspective, PLT has sent over 800 emails since launching on March 22, and by mid-April, PLT was sending nearly a third of all listserv emails. The inbox received, on average, about five emails a day, though sometimes it could go up to 11. I had successfully centralized student advertising, as much as a private actor really could.

Figure 2. A line graph showing how many emails were received in the PLT inbox daily during April 2021. Though the pilot started in March, I focus on the full month of April in this data analysis.

Many students greatly benefited from the existence of the centralized advertising platform. Students who did not know that one could sign up for multiple res college listservs (or were unwilling) now could send one easy email. Petitions and political action flourished; the first email we received in the inbox was a letter for the Princeton Community Center, which gained over 200 signatures within 24 hours.

One user told me that if it weren’t for PLT, he would not have been able to find his lost glasses. I also used PLT myself to see how we could cooperate in other ways as well: I designed a room draw spreadsheet and a senior sale spreadsheet, which both garnered well over 500 views.

Criticisms and insights

Analyzing the complaints led to many insights about PLT. The most common complaint was that Andrew was “spamming” and sending too many emails. Defenders of PLT noted that in an online semester, emails were the only way of advertising. These defenders also claimed that there were more listserv emails during an online semester, though this is actually empirically false. Take a look at these calculations:

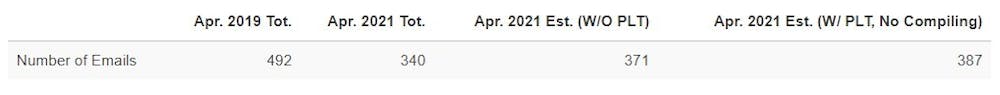

Figure 3. The total emails sent to the Forbes “Re-INNformer” listserv in April 2019 and April 2021. This also includes an estimate for April 2021 without the PLT intervention and an estimate for April 2021 without PLT’s email compilations.

Since April 2020 featured very few emails as a result of the sudden move-out due to the pandemic, I estimated the “W/O PLT” email volume by taking the percent change in emails from October 2019 (i.e., pre-pandemic) to October 2020 (i.e., when most people were settled into the rhythm of pandemic life, more similar to now). I then calculated the estimate by applying that percent change to April 2019’s listserv volume.

PLT also started compiling multiple emails into a single newsletter-like email every 24 hours, starting on April 19, in response to multiple feedback form suggestions. As such, I also estimated how many emails would be sent out without email compiling. The “No Compiling” estimate is 16 emails larger than our “W/O PLT” estimate, suggesting that PLT did improve access to listservs for people who otherwise would not have sent emails.

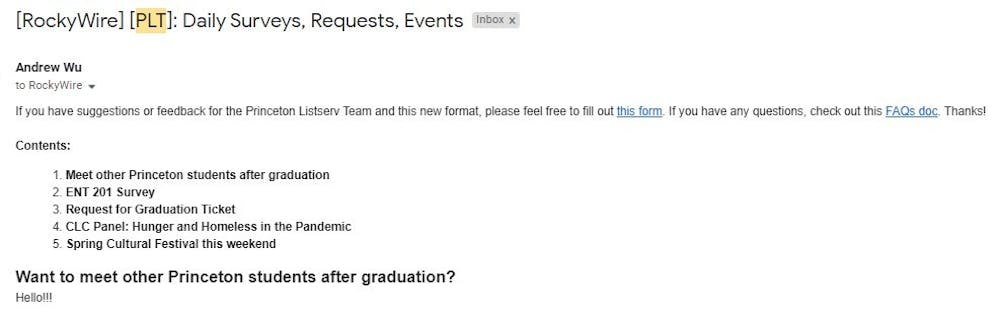

Figure 4. An early iteration of the PLT compilation email, combining multiple emails into a newsletter-like format.

Despite PLT theoretically increasing email volume, I would be surprised if anyone would notice 16 more listserv emails than usual, amidst hundreds of emails a month. Furthermore, if we continued to send emails in a non-compiled format, there would still be 105 fewer emails on the Forbes listserv in April 2021 than in April 2019. Email volume certainly did not reach historically unbearable levels.

This suggests that there is something about PLT emails that make them feel more frequent. Multiple feedback form responses suggested that seeing Andrew Wu’s name at the top of every email was limiting the amount of information that people could glean from an email at first glance; this forced people to open up the email for details, which took more time and energy.

If we want our emails to be more manageable, we should maximize the amount of information that one could glean from this first glance. One immediate change we made was adding a “[PLT]” tag to the subject lines of PLT emails, which was met with good reception by those who would rather skip email advertisements.

However, one still loses a lot of potentially interesting information by skipping over all PLT emails. So when we started compiling emails, we also started adding subject tags like “[SALE],” “[LOST AND FOUND],” and “[LECTURE].” This gives people the ability to make more informed choices about what messages they want to immediately look at, save for later, or delete.

Figure 5. A PLT compilation email, with subject tags to help readers manage emails at a glance.

A Subject-Based Solution to the Listserv Problem

So, what should we do, given the PLT pilot findings?

Leaving the system like this, where a single individual forwards all of these emails, is inefficient in the long run; it creates a dependency on a single entity, when we should try to give users as much choice and customization as possible. This dependence is also burdensome on the provider; there were days when Andrew had to meet deadlines for his independent work or prepare for finals, but people were also counting on him to send emails in a timely manner.

I propose that we make multiple centralized and accessible listservs in which people can sign up for subjects based on their interests.

Perhaps the different types of subjects could be refined from further research, but if a person only has interests in theatre events, then it is a bit much to ask them to sift through the 95 percent of irrelevant emails to not miss out on the 5 percent of theatre event emails. Unsubscribing from the current res college listservs is not an option because they do have that vested interest in the 5 percent; something must change to accommodate for people with selective interests.

If the chosen subjects are too restrictive, a general “News” listserv may also be a possibility. Think of it like the “#random” channel in Slack workspaces; anything can be posted there, but there should be other dedicated channels for more specific types of messages. Our system right now is more like having a Slack workspace with six different “#random” channels, which is chaotic.

I leave further details of how an ideal listserv system should function for readers to consider, but the take-home message is that even within individual res college listservs, we could be doing more to make emails easier to navigate.

The Future of PLT and the Hope for Systemic Change

The job of reforming the listserv system ultimately falls upon the next generation; since Andrew and I are graduating seniors, the PLT shall send its last email on Friday, May 21, unless we find a successor. Even if PLT is likely finished, I end this article series hoping someone will eventually pick up the work left behind.

I am fairly pessimistic that there will be an immediate successor to the PLT. Andrew fulfilled a rare set of qualities; not only was he subscribed to all six listservs, but he was also willing to do all of this work for not much benefit. He also took all of the hate mail and attention fairly well; we never expected PLT to blow up as much as it did, but Andrew handled it with grace.

Regardless, if you know someone that may be willing to take on the job, I encourage you to fill out the PLT Interest Form here.

Following the disappearance of PLT, we may end up back at the status quo. I have spent much time thinking about whether my efforts were all for nothing. Perhaps I was barking up obscure trees that no one really cared about; my previous opinion pieces on the YAT election and the 1903 Prize were fairly niche topics themselves, too.

Yet, I am optimistic that someone will pick up the mantle of listserv reform one day, because I picked up the mantle of some topics from my favorite ‘Prince’ Opinion writer, Liam O’Connor ’20. I wrote these articles because I was fascinated by O’Connor’s use of quantitative data to expose inefficiencies in the functioning of the University, especially in his pieces on demographics and awards, which I have referenced in my own articles.

Perhaps one day someone will dig up these articles and build upon them, much as I have tried to do with O’Connor’s work. Systemic change is predicated on getting many people to advocate for issues over time — for generations to continue the fight and build towards a better future.

My message to all of you working on changing pre-existing systems: you’re doing great. Keep it up. Leave a footprint behind so that the next generation will pick up where you left off.

We come into this University entrenched in traditions that we don’t quite understand yet must initially accept as confused first-years. Reversing suboptimal conventions takes widespread justification, coordination, and motivation to overcome the inertia of the institution. One day, with enough effort over time, we can and we will make change.

But in the meantime, don’t forget to check your email. There are always some hidden gems among the spam.

Daniel Te ’21 is an alumnus of the philosophy department from Woodbridge, Va. He can be reached at danielte@princeton.edu or te.daniel44@gmail.com.